The Books of Kings

About

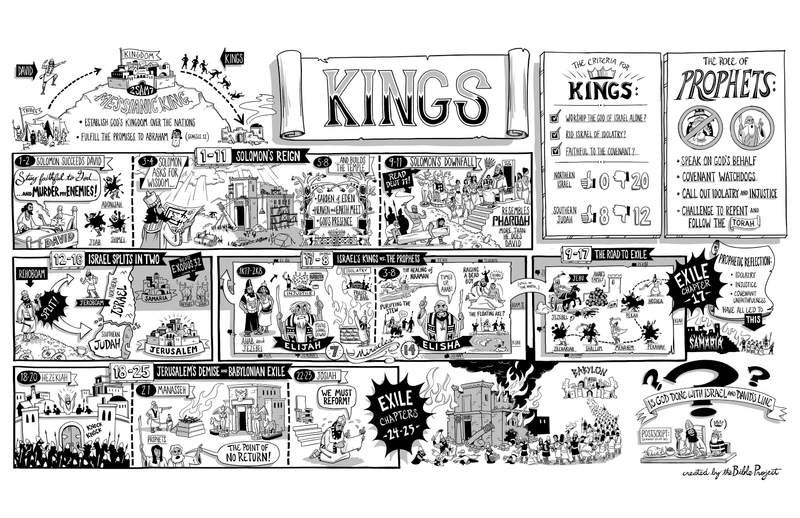

Although the books of 1 and 2 Kings are two separate books in our Bibles, they were originally written as one book telling a unified story. In the previous book of Samuel, David had unified the tribes of Israel into a single kingdom. God promised that from David’s line would come a messianic king who would establish God’s Kingdom over the nations and fulfill the promises made to Abraham. The books of Kings tell the story of the long line of kings that came after David, but none of them live up to the promise. In fact, they run the nation of Israel right into the ground.

The books are structured into five main movements. They begin and end with a focus on Jerusalem, first with Solomon’s reign and the construction of the temple (1 Kgs. 1-11) and ending with Jerusalem’s destruction and Israel’s exile to Babylon (2 Kgs. 18-25). The story leading up to this tragedy makes up the three center sections. They explain how Israel split into two rival kingdoms (1 Kgs. 12-16), how God tried to prevent the corruption of Israel and its kings by sending the prophets (1 Kgs. 17-2 Kgs. 8), and how exile became an unavoidable consequence of Israel’s sin (2 Kgs. 9-17).

1 Kings 1-11: Solomon’s Rise and Moral Failure

The opening chapters show how the kingdom of Israel passed from an aging, decrepit David to his son Solomon. David’s final words to Solomon are similar to those of Moses, Joshua, and Samuel. It is a call to remain faithful to the commands of the covenant and to offer allegiance to the God of Israel alone. However, his words ring somewhat hollow, as David and Solomon then conspire to consolidate the new kingdom through a series of political assassinations. Already, the story is not off to a great start.

Solomon’s brightest moments come when he asks God for wisdom to lead Israel and even completes David’s dream of building a temple for the God of Israel (1 Kgs. 3-8). The story actually pauses here to describe the design of the temple in detail. Just like the tabernacle in the Torah, the gold and jewels and the depictions of angels and fruit trees all symbolize and call back to the garden of Eden—the place where Heaven and Earth meet and where God dwells peacefully among his people.

As soon as Solomon finishes the temple, he makes some really horrible choices, and his kingdom begins to fall apart. He starts marrying the daughters of other kings (hundreds of them!) for political alliances and adopting their gods and introducing their worship into Israel. He then accumulates huge amounts of wealth, builds an enormous army, and institutes slave labor for all his building projects. If you go look at God’s guidelines for Israel’s kings in Deuteronomy 17, Solomon breaks every one. By the time he dies, he resembles Pharaoh more than he does David.

1 Kings 12-16: The Kings of Northern Israel and Southern Judah

The next section of the book opens with Solomon’s son Rehoboam mimicking his father in a sad story of greed and lust for power. He tries to increase taxes and slave labor, but, under the leadership of Jeroboam, the northern tribes of Israel rebel and secede to form their own rival kingdom. We are left with southern Judah, centered in Jerusalem with kings from the line of David, and this new northern kingdom, called Israel, whose eventual capital will be Samaria. Jeroboam also builds two new temples to compete with the one Solomon built, and he places a golden calf in each to represent the God of Israel. It’s a tragic replay of the story of Israel’s failure in Exodus 32.

From chapter 12 onwards, the story goes back and forth, from north to south, tracing the fate of both kingdoms. Each had about 20 successive kings, and as the author introduces each one, he evaluates their reign by a few criteria. Did they worship the God of Israel alone, or did they promote the worship of other gods? Did they deal with idolatry among the people? And finally, did they remain faithful to the covenant like David, or did they become corrupt and unjust? Using these criteria, the author finds that no good kings come out of northern Israel, and from southern Judah, only eight out of 20 get a positive rating.

This connects to another strategic purpose of the books of Kings—to introduce the role of the prophets who are key figures in Israel’s history. In the Bible, prophets were not fortune tellers. Rather, they spoke on behalf of the God of Israel and played the role of covenant watchdogs, calling out idolatry and injustice among the kings and the people. They constantly reminded Israel of their calling to be a light to the nations by obeying the commands of the Torah, and so they challenged Israel to repent and follow their God.

1 Kings 17-2 Kings 17: Elijah, Elisha, and the Exile of Israel

For each king, God raised up prophets to hold them accountable. The most prominent are the northern prophets, Elijah and his disciple Elisha. Elijah was a wild man of a prophet who lived in the desert. His archnemeses were the northern king, Ahab, and his wife Jezebel. Together they had instituted worship of the Canaanite god Baal all over Israel. In a famous story, Elijah challenged 450 prophets of Baal to a contest to see which God was real. They all built altars and prayed to their gods, but only the God of Israel answered with fire. In another story, Ahab uses his royal power to murder an Israelite farmer and steal the family’s vineyard. Elijah again confronts Ahab’s injustice and announces the downfall of his house.

Elijah eventually passes the mantle of his prophetic leadership to a young disciple named Elisha, who asks God for twice the power and authority of Elijah. What’s fascinating is how the author recounts seven miraculous feats of Elijah and then offers stories of 14 acts of power from Elisha. While both prophets were clearly remarkable men and played the same role of confronting Israel’s kings for the idolatry and injustice they caused, ultimately they were unsuccessful in turning Israel back from apostasy.

The next section begins in 2 Kings 9 as the northern kingdom is rocked from a bloody revolution by a king named Jehu who destroys Ahab’s family. Although he was first commissioned by God, his violence becomes excessive and creates a spiral of political assassinations and rebellions from which northern Israel never recovered. Coup after coup follows Jehu as each king worships other gods and allows gross injustice. It all leads up to 2 Kings 17 when the big bad empire of Assyria swoops down and takes out the northern kingdom altogether. The capital city of Samaria is conquered, and the Israelites are exiled and dispersed throughout the ancient world.

2 Kings 17 is key because the author stops the story and offers a prophetic reflection on all that’s happened so far. He blames the downfall of the northern kingdom on the idolatry and covenant unfaithfulness of Israel and its kings. Because of their sins, God allowed his people to face the consequences of their decisions.

2 Kings 18-25: Final Kings in Judah and Exile to Babylon

The final movement of the books of Kings tells the story of the lone southern kingdom of Judah. Here we meet some pretty heroic kings, like Hezekiah, who trusts God when the armies of Assyria come knocking at Jerusalem’s door. Or Josiah, who discovers a lost scroll of the Torah in the temple and, after reading it, institutes reforms to try to remove all the idols and Canaanite influences in the land. But alas, Judah is too far gone. The king in between Hezekiah and Josiah, named Manasseh, is the worst by far. He not only introduces the worship of idol statues into the Jerusalem temple, but he also institutes child sacrifice. God sends prophets to say that the time has come. Israel has reached a point of no return.

The final chapters, 2 Kings 24-25, tell the story of the Babylonian empire coming to invade Jerusalem, destroy the temple, and carry the people and the royal line of David off into exile. The story ends leaving us wondering: Is God done with Israel and the line of David?

Well, the final paragraph jumps 40 years ahead, into the Babylonian exile. We find here an odd short story about Jehoiachin, a descendant from David who would have been king in Jerusalem. The king of Babylon releases Jehoiachin from prison and invites him to eat at the royal table for the rest of his life (2 Kgs. 25:27-30). It’s not much, but the story offers a glimmer of hope that God has not abandoned his promise to David. And it’s that hope that gets explored further in the wisdom and prophetic books of the Bible.