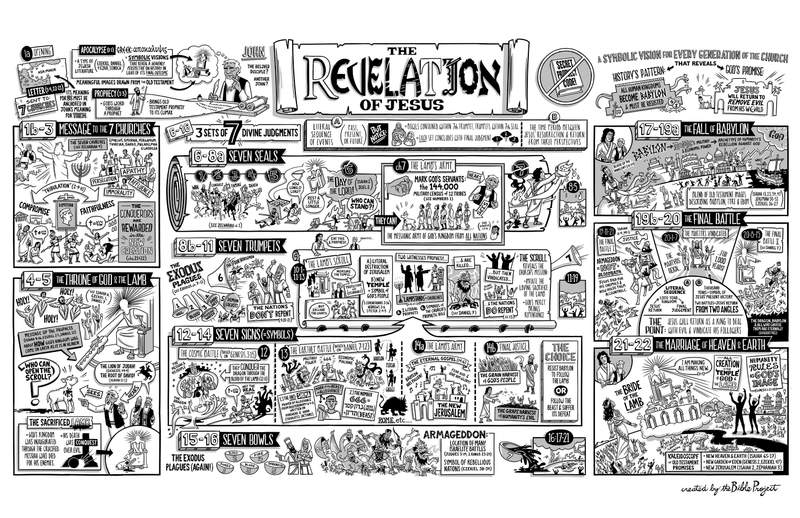

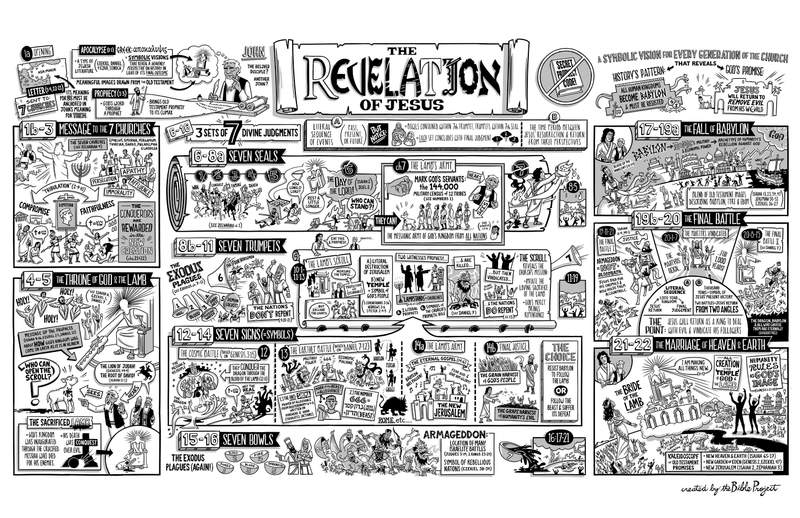

The Book of Revelation

About

In the opening paragraph, the author identifies himself as John, which could refer to the author of the Gospel and letters of John, or it could be another leader in the early Church. Whichever John it was, he makes it clear in the opening paragraph that this book is a “revelation.” The Greek word used here is apokalypsis, which refers to a type of literature found in the Hebrew Scriptures and in other popular Jewish texts. Jewish apocalypses recounted a prophet’s symbolic visions that revealed God’s heavenly perspective on history so that the present could be viewed in light of history’s final outcome. These texts use symbolic imagery and numbers not to confuse but to communicate. Almost all the imagery is drawn from the Old Testament, and John expects his readers to interpret by looking up the texts to which he alludes.

Revelation 1-3: Jesus’ Words to Seven Churches in Asia Minor

John says that this apocalypse is a prophecy. A prophecy is a word from God spoken through a prophet to comfort or challenge God’s people. This apocalyptic prophecy was sent to real people that John knew. The book opens and closes as a circular letter, which was sent to seven churches in the ancient Roman province of Asia. The fact that The Revelation is a letter means that John was specifically addressing these first century churches. While this book has a lot to say to Christians of later generations, its meaning must first be anchored in the historical context of John’s time and place.

John says he was exiled on the island of Patmos, where he saw a vision of the risen Jesus standing among seven burning lights. The image, adapted from Zechariah 4, is a symbol of seven local churches in Asia Minor. Jesus addressed the specific problems facing each church. Some were apathetic due to wealth and affluence, while others were morally compromised. But there were others who remained faithful to Jesus and were suffering harassment and persecution. Jesus warned them that a “tribulation” was upon the churches that would force them to choose between compromise or faithfulness.

By John’s day, the murder of Christians by the Roman emperor Nero had passed, and the persecution by emperor Domitian was likely underway. Jesus calls the churches to faithfulness, by which they will “conquer” and receive a reward in the final marriage of Heaven and Earth. The opening section sets up the main plot tension throughout the book. Will Jesus’ people conquer and inherit the new world that God has in store? And why is faithfulness to Jesus described as “conquering?”

Revelation 4-5: Vision of the Heavenly Throne Room and First Judgment

John’s next vision is of God’s heavenly throne room, described with images from many Old Testament prophetic books. Around God are creatures and elders, representing all creation and human nations, who are giving honor and allegiance to the one true God. In God’s hand is a scroll with seven wax seals, symbolizing the scrolls of the Old Testament prophets and Daniel’s visions. Their message was about how God’s Kingdom would come on Earth as in Heaven.

However, no one is qualified to open the scroll until John finally hears of the one who can. It’s “the Lion of the tribe of Judah” and the “Root of David” (Gen. 49:9; Isa. 11:1). These are classic Old Testament descriptions of the messianic King who would bring God’s Kingdom through military conquest. That’s what John hears, but what he sees is not a lion-king but a sacrificed, bloody lamb who is alive again, standing ready to open the scroll.

This symbol of Jesus as the slain lamb is crucially important for understanding the book. John is saying that the Old Testament promise of God’s future Kingdom was inaugurated through the crucified Messiah. Jesus died for his enemies as the true Passover lamb so that others could be redeemed. His death on the cross was his enthronement and his “conquering” of evil. The vision concludes with the lamb alongside the one on the throne, and together they are worshiped as the one, true Creator and redeemer. The slain lamb then begins to open the scroll, a symbol of his divine authority to guide history to its conclusion.

This brings us into the next section of the book with three cycles of sevens: seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls. Each cycle depicts God’s Kingdom and justice coming on Earth as in Heaven. Some people think these three sets of seven divine judgments represent a literal, linear sequence of events that happened in the past or present, or will happen when Jesus returns. Notice, however, that John wove them together. The seven bowls come out of the seventh trumpet and the seventh seal, and the seven trumpets emerge from the seventh seal. They’re like nesting dolls, each seventh containing the next seven. And each series culminates in the final judgment, all with matching conclusions. Because of this, it’s more likely that John is using each set of seven to depict three distinct perspectives of the same period of time after Jesus’ resurrection.

Revelation 6-8a: Vision of the Lord’s Slain Servants

As the lamb opens the scroll’s first four seals, John sees four symbolic horsemen (an image from Zechariah 1) who symbolize times of war, conquest, famine, and death. The fifth seal depicts the murdered Christian martyrs before God’s heavenly throne. The cry of their innocent blood rises up before God, and they’re told to rest because, sadly, more Christians are going to die. The sixth seal is God’s ultimate response to their cry. He brings the great Day of the Lord described in Isaiah 2 and Joel 2. The people of the earth cry out, “Who is able to stand?!”

At this point, John pauses the action to answer that question. He sees an angel with a signet ring coming to place a mark of protection on God’s servants enduring all this hardship. He then hears the number of those sealed: 144,000. It’s a military census of twelve thousand from each of the twelve tribes of Israel (Numbers 1). Now, the number of this army is what John heard, just like he heard about the conquering lion of Judah. In both cases, what he turned and saw was the surprising fulfillment through Jesus, the slain lamb. John is seeing the messianic army of God’s Kingdom. It’s made up of people from all over the world, fulfilling God’s ancient promise to Abraham. This multiethnic army of the lamb can stand before God because they’ve all been redeemed by his blood. They are called forth to conquer not by killing their enemies but by suffering and bearing witness like the lamb. With this, the seventh and final seal is broken. But before the scroll is opened, the seven warning trumpets emerge, and only then does the Day of the Lord come to bring final justice once and for all.

Revelation 8b-11: Visions of Judgment, the Temple, and Two Witnesses

When we come to the seven trumpets, John backs up and retells the story once again, this time with images from the Exodus story. The first five trumpet blasts replay the plagues sent upon Egypt, while the sixth trumpet releases the four horsemen from the first four seals. John then tells us that, despite these plagues, “the nations did not repent,” just like Pharaoh. God’s judgment alone does not bring people to humble themselves before him.

John then pauses the action again. An angel brings John the unsealed scroll that was opened by the lamb. John is now told to eat the scroll and proclaim its message to the nations. Finally, the lamb’s scroll is open, and we discover how God’s Kingdom will ultimately come.

The scroll’s content is spelled out in two symbolic visions. First, John sees God’s temple and the martyrs within it, and he is told to measure and set it apart (it’s an image of protection drawn from Zech. 2:1-5). The outer courts and city, however, are excluded and trampled by the nations. Some think that this refers literally to a destruction of Jerusalem in the past or the future. But it’s more likely that John is using the new temple as a symbol for God’s new covenant people, just like the other apostles did (1 Cor. 3:16; Heb. 3:6; 1 Pet. 2:4-5). The vision shows that while Jesus’ followers may suffer persecution, this external defeat cannot cancel their victory through the lamb.

This idea is elaborated in the scroll’s second vision. God appoints two witnesses as prophetic representatives to the nations. Some think that this refers literally to two prophets who will appear one day. However, John calls these characters “lampstands,” one of his clear symbols for the churches (Rev. 1:20). It’s likely that this vision is about the prophetic role of Jesus’ followers, who like Moses and Elijah, are to call idolatrous nations and rulers to turn to God. Then a horrible beast appears, who conquers the witnesses and kills them (remember Daniel 7). But God brings the witnesses back to life and vindicates them before their persecutors. This results in many among the nations repenting and giving honor to the creator God.

Let’s pause and think about the story so far. God’s warning judgments through the seals and the trumpets did not generate repentance among the nations. Now the lamb’s scroll reveals the strange mission of his army. God’s Kingdom is revealed when the nations see the Church imitating the sacrifice of the lamb and loving their enemies instead of killing them. It’s God’s mercy, shown through the Church, that will move the nations to repentance. After this, the last trumpet sounds, and the nations are shaken as God’s Kingdom comes on Earth as in Heaven.

The message of the scroll is finished, but who was that terrible beast who declared war against God’s people? John turns to this question in the second half of The Revelation.

Revelation 12-16: Visions of the Dragon, Beasts, 666, and More

After exploring the surprising message of the lamb�’s opened scroll, John offers a series of seven visions that he calls “signs” (Rev. 12-15). That word means “symbol,” and these chapters are full of them. The purpose of these visions is to expand further on the message of the lamb’s scroll.

The first sign reveals the cosmic, spiritual battle behind the Roman empire’s persecution of Christians, the ancient conflict that started in Genesis 3:15. The serpent in the garden of Eden, the source of all spiritual evil, is depicted here as a dragon. It attacks a woman and her seed, who represent the Messiah and his people. But the Messiah defeats the dragon through his death and resurrection, casting him to Earth. There, the dragon may inspire hatred and persecution of the Messiah’s people, but God’s people will conquer him by resisting his influence, even if it kills them. John is showing the seven churches that neither Rome nor any other nation or human is the real enemy. There are dark spiritual powers at work that can be conquered only when Jesus’ followers remain faithful and love their enemies.

John’s next vision replays the same conflict, this time with the symbolism of Daniel’s animal visions (Dan. 7-12). John sees two beasts, one representing national military power that conquers through violence. The other beast symbolizes the economic propaganda machine that exalts this power as divine and demands full allegiance from all nations. This is symbolized by taking the mark of the beast and his number 666 on the forehead or hand.

The meaning of this image is found in the Old Testament. The mark is the “anti-Shema.” The Shema is an ancient Jewish prayer of allegiance to God found in Deuteronomy 6:4-8. It was to be written on the Israelites’ foreheads and hands as a symbol of devoting all your thoughts and actions to the one true God. But now the rebellious nations demand their own god-like allegiance.

The number of the beast is also a symbol. John was fluent in both Hebrew and Greek, and his readers knew that Hebrew letters also function as numbers. If you spell the Greek words “Nero Caesar” or “beast” in Hebrew, both amount to 666. John isn’t saying that Nero was the precise fulfillment of this vision; rather, he’s a recent example of the pattern explored in Daniel. Human rulers become beasts when they assign divinity to their power and economic security and demand total allegiance to it. Babylon was the beast of Daniel’s day, followed by Persia, then Greece, and now Rome in John’s day. The pattern stands for any later nation who acts the same.

Standing opposed to the dragon’s beastly nations is another king, the slain lamb and his army, who have given their lives to follow him. From the new Jerusalem, their song goes out to the nations as “the eternal Gospel” (Rev. 14:6). All people are called to repent, worship God, and come out of Babylon. Then John sees a vision of final justice, symbolized by two harvests. One is a good grain harvest where King Jesus gathers up his faithful people. The other is a harvest of wine grapes, representing humanity’s intoxication with evil, which are taken to the wine press and trampled. With these “sign” visions, John places a choice before the seven churches. Will they resist Babylon and follow the Lamb, or will they follow the beast and suffer its defeat?

John then replays a final cycle of seven divine judgments, symbolized as seven bowls. Similar to the Exodus plagues, the bowls do not bring about repentance but the opposite. The people resist and curse God just like Pharaoh. With the sixth bowl, the dragon and beasts gather the nations together to make war against God’s people in a place called Armageddon. This refers to a plain in northern Israel where many battles had been fought against invading nations (Jud. 5:19; 2 Kgs. 23:29). Some think that this image refers literally to a future battle, while others think it’s a metaphor for final judgment. Either way, John has taken these images from Ezekiel 38-39, where God battles Gog, who is of rebellious humanity. And so in the seventh bowl, evil is defeated among the nations once and for all.

Revelation 17-20: The Final Battle of Armageddon

Now that John has fully unpacked the message of the lamb’s unsealed scroll, he expands upon three key themes introduced earlier: the fall of Babylon, the final battle to defeat evil, and the arrival of the new Jerusalem. Each one explores the final coming of God’s Kingdom from a different angle.

John is shown a stunning woman who is dressed like a queen but drunk with the blood of the martyrs and all innocent people. She is riding the dragon from the sign visions and is called Babylon the prostitute. All the detailed symbols of this vision were clear to John’s first readers because he was depicting the military and economic power of the Roman empire. But there’s more to it. The vision quotes language and imagery from every Old Testament passage about the downfall of Babylon, Tyre, and Edom (Isa. 13; Isa. 23; Isa. 34; Isa. 47; Jer. 50-51; Ezek. 26-27). He’s showing that Rome is simply the newest version of that old archetype of humanity in rebellion against God. Nations that exalt their own economic and military security to divine status aren’t limited to the past or the future. Babylons will come and go, leading up to the day when Jesus returns to replace them all with his Kingdom.

Up to this point in the book, the Day of the Lord has been depicted as a day of fire, earthquake, or harvest. Here at the conclusion of the book, it is described as a final battle (Rev. 19:11-21; Rev. 20:7-15) that results in the vindication of the martyrs (Rev. 20:1-6). John takes us back to the sixth bowl as the nations gather to oppose God. Jesus appears as the great hero, riding a white horse and ready to “conquer” the world’s evil. Notice, however, that he’s covered with blood before the battle even begins (Rev. 19:13). It’s his own. And his only weapon is “the sword of his mouth,” an image adapted from Isaiah 11:4 and 49:2.

John is trying to tell us that Armageddon is not a bloodbath. The same Jesus who shed his blood for his enemies comes proclaiming justice, holding accountable those who refuse to repent of the ruin they’ve caused in God’s good world. The destructive hellfire that they have caused in the world justly becomes their God-appointed destiny.

After this, John sees a vision of Jesus’ followers who have been murdered by Babylon. They are brought to life to reign with the Messiah for one thousand years. After this, the dragon once again rallies the nations of the world to rebel against God, but they are all brought before God’s throne of justice and face the consequences of eternal defeat. The forces of spiritual evil and all those who do not want to participate in God’s Kingdom are destroyed. They are given what they want, which is to exist by themselves and for themselves. The dragon, Babylon, and all those who choose them are eternally quarantined, unable to spoil God’s new creation ever again.

There’s a lot of debate about the relationship between the one thousand years that comes in between these two battle scenes. Some think that it refers to a literal, chronological sequence of Jesus’ return, followed by his one thousand year Kingdom on earth and final judgment. Others think the one thousand years are a symbol of Jesus and the martyr’s present victory over spiritual evil, while the two battles depict Jesus’ future return from two different angles. Whichever view you take, the point is that John promises the return of King Jesus to deal with evil forever and vindicate those who have been faithful to him.

The book concludes with a vision of the marriage of Heaven and Earth (Rev. 21:1-22:9). An angel shows John a stunning bride, symbolizing the new creation that comes to forever join God and his covenant people. God announces that he has come to live together with humanity forever and make all things new (Rev. 21:5).

Revelation 21-22: The New Heaven and Earth

This vision is a kaleidoscope of Old Testament promises. It depicts a new Heaven and Earth (Isa. 65:17), a restored creation that’s been healed of the pain and evil of human history. It’s also a new garden of Eden (Gen. 2) and paradise of eternal life with God. However, it’s not simply a return to the garden; it’s also a step forward into the new Jerusalem (Isa. 2). It’s a great city where human cultures in all their diversity work together in harmony. But in the most surprising twist, there is no temple. The presence of God and the lamb, once limited to the temple, now permeates every inch of this new world. This is when the new humanity will fulfill the calling that was placed on them back on page one of the Bible (Gen. 1:26-28), to rule as God’s image and partner with God in taking his creation into new, uncharted territory.

So ends both John’s apocalypse and the epic story of the Bible. John did not write this book as a secret code for deciphering the timetable of Jesus’ return. It is a symbolic vision that brought challenge and hope to the seven first-century churches and every generation since. It reveals history’s pattern and God’s promise, showing how every human kingdom eventually becomes Babylon and must be resisted. But the Messiah, Jesus, who loved and died for our world, will not let Babylon go unchecked. He will return one day to remove evil from his good world and make all things new. This promise should motivate faithfulness in every generation of God’s people until the King finally returns.