The Book of Esther

About

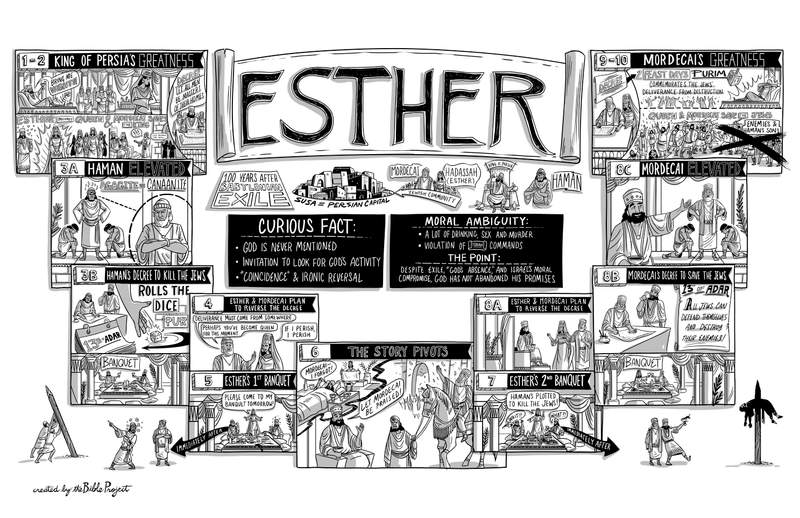

This is one of the more exciting and curious books in the Bible. The story is set over 100 years after the Babylonian exile of the Israelites from their land. While some Jews did return to Jerusalem (see Ezra-Nehemiah), many did not. The book of Esther is about a Jewish community living in Susa, the capital city of the ancient Persian empire. The main characters are two Jews, Mordecai and his niece Esther. Then there is the king of Persia and the Persian official Haman, the cunning villain.

Esther is a curious book in the Bible because God is never mentioned, not once. This may strike you as odd because the Bible is supposed to be a book about God. However, this is a brilliant technique by the anonymous author. It’s an invitation to read the story looking for God’s activity, and there are signs of it everywhere. The story is full of odd coincidences and ironic reversals that force you to see God’s purpose at work behind every scene.

Esther 1-2: Esther Becomes Queen

The story begins when the king of Persia throws two elaborate banquet feasts that last a total of 187 days, all for the grandiose purpose of displaying his greatness and splendor. On the last day of the feast, the king is drunk and demands that his wife, Queen Vashti, appear at the party to show off her beauty. She refuses, and, in a drunken rage, the king deposes Vashti and makes a silly decree that all Persian men should be the master of their own homes.

Then the king holds a beauty pageant to find a new queen. And right when the story feels like a bad soap opera, we’re introduced to Esther and Mordecai. Esther hides her Jewish identity and poses as a Persian, and she wins the pageant. The king is so obsessed with Esther that he elevates her as the new queen of Persia. After this, Mordecai “just happens” to overhear two royal guards plotting to murder the king. He informs Esther, who then tells the king, and Mordecai gets credit for saving the king’s life. And in all these remarkable events, God is not mentioned, but it all seems so providentially ordered. What is God up to?

Esther 3-6: Haman’s Plot and Mordecai’s Rise to Power

We begin to find out in the next part of the story. We’re introduced to Haman, who’s not a Persian but an Agagite, a descendant of the ancient Canaanites (1 Sam. 15). The king elevates Haman to the highest position in the kingdom and demands that all kneel before him. But when Mordecai sees Haman, he refuses to kneel. Haman is filled with rage. When Haman finds out that Mordecai is Jewish, he successfully persuades the king to enact a decree to destroy all the Jews. They decide the date of this horrific day in an outrageous way. Haman rolls ancient dice (pur in Hebrew), and the decree is set. Eleven months later, on the 13th of Adar, all the Jews will be executed. Haman and the king throw a party to celebrate the decree.

After this, the story focuses on Mordecai and Esther, who are now the only hope for the Jewish people. They plan for Esther to reveal her Jewish identity to the king and ask that he reverse the decree (ch. 4). But there’s risk involved because approaching the king without a royal request was an act worthy of death, according to Persian law. At a crucial moment in the story, Mordecai asserts that if Esther remains silent, “deliverance for the Jews will arise from another place.” Then he wonders aloud, “Who knows, maybe you’ve become queen for this very moment!” Esther responds with bravery, “If I perish, I perish,” and she decides to approach the king.

We then see an ironic reversal of all of Haman’s evil plans. Esther hosts the king and Haman at a banquet, where she makes a special request that they both come to an even more exclusive banquet the next day. Haman leaves the feast quite drunk and happy with himself, and he sees Mordecai in the street. When Mordecai doesn’t bow, Haman fumes with anger and orders that a tall stake be built, so that Mordecai can be impaled upon it in the morning.

It seems things can’t get any worse for the Jews or for Mordecai. But all of a sudden, the story pivots in chapter 6. That night, the king can’t sleep, so he has the royal chronicles read to him. He just happens to hear about how Mordecai saved the king’s life from the plot of the guards. The king had totally forgotten about it! So in the morning, as Haman enters to request Mordecai’s execution, the king orders Haman to honor Mordecai publicly for saving his life. Haman then has to lead Mordecai about the city on a royal horse. This reversal forms a turning point in the story, beginning with Haman’s downfall and ending with Mordecai’s rise to power.

Esther 7-8: Haman’s Demise and the Jewish People’s Deliverance

The next day, Esther hosts the second banquet (ch. 7). The king and Haman arrive, and Esther informs the king of her Jewish identity. Then she reveals that Haman’s decree is a ploy to murder her and Mordecai, the man who saved the king’s life! After taking in a lot of wine and Esther’s news, the king goes into a drunken rage (notice how many of those you find in this story). He orders that Haman be impaled on the stake he made for Mordecai. It’s an ironic and grisly way to go.

But Haman’s execution doesn’t solve the problem of the decree to kill all the Jews. So the focus turns back to Mordecai and Esther as they plan to reverse the decree. When they discover that the king can’t revoke a decree he’s already made, Mordecai is commissioned to issue a counter-decree. On the day when all the Jewish people were to be killed, the people can now defend themselves and destroy any who plotted to kill them. After this, Mordecai, Esther, and Jewish people everywhere hold banquets and feasts to celebrate the new decree. Most surprising of all, Mordecai is elevated to a seat beside the king. Who saw that coming?!

Esther 9-10: The Jewish People Triumph

Eventually, the decreed day comes, and the Jews triumph over their enemies. First, they destroy Haman’s family along with any other Persian officials who had joined Haman’s plot. The next day, the Jewish people are allowed to destroy anyone who plotted against them. This is followed by great joy and celebration because the Jewish people have been rescued from annihilation.

The story then tells how Esther and Mordecai establish another decree. This great reversal and rescue will be memorialized by an annual two-day feast called Purim, named after Haman’s fateful dice. The book concludes with a short epilogue. Mordecai is elevated to second-in-command in the kingdom, and we’re told of his royal greatness and splendor as the Jews thrive in exile.

The Design and Message of the Book of Esther

Now, if you back up and look at the book as a whole, you can see how precisely the story has been designed. The story is full of many moments of ironic reversal, but notice how the entire book is structured as one large reversal, right down to the details.

The king’s splendor, feasts, and decrees in chapter 1 correspond to Mordecai’s splendor, feasts, and decrees in chapter 10. Esther and Mordecai first saved the king in chapter 2, and in the end they saved all the Jewish people in chapter 9. Haman’s elevation, edicts, and banquet with the king in chapter 3 are reversed by Mordecai’s elevation, edict, and banquet in chapter 8.

Also notice how Esther and Mordecai’s two planning scenes (chs. 4 and 8) and Esther’s two special banquets (chs. 5 and 7) form a frame around the greatest reversal in the whole story—Haman’s humiliation and Mordecai’s exaltation (ch. 6).

Another fascinating feature of the book is the moral ambiguity of the characters. There is a lot of drinking, anger, sex, and murder, and Mordecai and Esther participate in at least some of it. Also notable is their violation of many commands in the Torah (like marrying Gentiles or eating impure food). And so the story doesn’t seem to put them forward as impeccable moral examples, nor does it endorse all of their behavior. However, they are presented as models of trust and hope in the midst of terrifying circumstances.

In fact, this focus on Mordecai and Esther’s hope brings us all the way back to the curious feature of this book, that God is never mentioned. When God’s people are in exile, unable to obey the Torah perfectly, and when God seems absent, does this mean God is done with Israel? Has he abandoned his promises?

The book of Esther says no.

The story invites us to see that God can and does work in the mess and moral ambiguity of human history, using the faithfulness of even morally compromised people to accomplish his purposes.

The book of Esther asks us to trust in God’s providence even when we can’t see it working. That requires a posture of hope, to believe that, no matter how horrible things get, God is committed to redeeming his good world and overcoming evil. That’s what the story of Esther is all about.