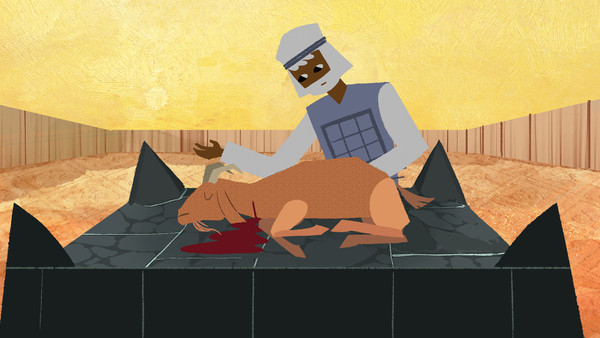

Sacrifice and Atonement

God is on a mission to remove evil from his good world, along with all of its corrosive effects. However, he wants to do it in a way that doesn’t involve removing humans. In this video, we trace the theme of God’s “covering” over human evil through animal sacrifices that ultimately point to Jesus and his death and resurrection.

Reflect

Imagine a world of peace, justice, and love. In a world like this, how would people communicate with one another? How would people spend time and money? How would authority figures use their power?

When people neglect to act with peace, justice, and love, it wreaks havoc—we call this evil. What is one way our relationships and the surrounding environment suffer from evil (e.g., Genesis 4:10-12, Romans 8:22-23)?

In order to heal this suffering, something first must be done to remove the evil. But what would happen if God removed everything contributing to the evil in the world? Would anyone remain alive? Discuss this predicament as a group and, if needed, review the video (0:22-1:07).

Discuss how God resolves this predicament through animal sacrifice and later through Jesus’ sacrifice. What does animal sacrifice represent? What is one way that Jesus is a more perfect sacrifice? Review the video or dive deeper by reading Hebrews 9:6-14.

Read Matthew 26:26-28. What is one practical way we can remember Jesus’ sacrifice? What is one specific way we can imitate Jesus’ sacrifice and repair relationships (e.g., John 15:9-13, Matthew 5:23-24, and Colossians 3:12-14)?

View Guide

Downloads

Biblical Themes

The Wilderness

Why does God sometimes lead his people into harsh and isolated places? Trace the theme of the wilderness through the story of the Bible and discover how trusting God in the wilderness prepares us for life in the garden.

Redemption

What if “redemption” means more than making something better? Discover how ancient biblical writers understood it as the cosmic work of rescue—where the creator reclaims his people to bring them home.

The Exodus Way

The story of Israel’s exodus from Egypt can be described as the way out of slavery, the way through the wilderness, and the way into the promised land. And this journey is actually a narrative theme that runs through the whole story of the Bible.

The Mountain

Watch a short video that explains what mountains represent in the Bible. Learn the key role mountains play throughout the unified story that leads to Jesus.

Heaven & Earth

What does the Bible really teach about Heaven, and what is Heaven’s relationship to Earth? In this video, we explore the surprising biblical viewpoint that Heaven and Earth were meant to overlap and how Jesus is on a mission to bring them together once and for all.

The Messiah

Explore the mysterious promise on page three of the Bible, that a promised deliverer would one day come to confront evil and rescue humanity. We trace this theme through the family of Abraham, the messianic lineage of David, and ultimately to Jesus who defeated evil by letting it defeat him.

The Covenants

Despite human rebellion, God continues to make covenant promises to restore humanity to the role they were created for: to be partners with God in ruling creation. Though humans repeatedly fail, Jesus fulfills humanity’s side of the partnership, making right the relationship between God and humankind.

Holiness

God’s holiness presents a paradox to human beings. God is the unique and set-apart Creator of all reality and the author of all goodness. However, that goodness can become dangerous to humans who are morally corrupt. Ultimately, this paradox is resolved by Jesus, who embodies God’s holiness that came to heal his creation.

Sacrifice and Atonement

God is on a mission to remove evil from his good world, along with all of its corrosive effects. However, he wants to do it in a way that doesn’t involve removing humans. In this video, we trace the theme of God’s “covering” over human evil through animal sacrifices that ultimately point to Jesus and his death and resurrection.

The Law

What is the importance of the ancient laws in the Hebrew Bible? Are they even relevant for Jesus followers? Explore how much the laws can teach us about God’s character and the significance of Jesus’ ministry on Earth.

Gospel of the Kingdom

Gospel is a word that means “good news,” but it’s more than that. It’s a royal announcement, and its use in the New Testament points to the radical announcement of God’s Kingdom coming to Earth through Jesus. The Gospel fulfills the promises of the Hebrew Bible, as we see Jesus bring God’s reign and rule in a way no one expected.

Image of God

What does it mean for humans to be made in God’s image? In the opening pages of Genesis, we see God create humanity as his co-rulers of creation, but things quickly go wrong when humans rebel and forfeit their role. Jesus comes to set right humanity’s rebellion, opening up a new way of being human through his life, death, and resurrection.

Day of the Lord

Does God still care about the destruction humans have caused in his good world? The story of the Bible shows us how God confronts human evil, as well as the deeper spiritual evil that is at work on Earth. Ultimately, we see how Jesus responds to the problem of evil by allowing his death on the cross.

Holy Spirit

In this video, we explore the original meaning of the biblical concept of spirit (ruakh) and what it means that God’s Spirit is personally present in all of creation. Ultimately, the Spirit was revealed through Jesus and sent out into the lives of his followers to bring about the new creation.

Public Reading of Scripture

Reading the Bible aloud with a group of people is an ancient practice. In fact, the origins of the Bible are rooted in public readings among members of the community. Explore the origins and development of this fascinating biblical topic, and see how it offers us a model for engaging the Scriptures in our own day.

Justice

Justice is a felt need in our world today and a controversial topic. But what is justice exactly, and who gets to define it? In this video, we'll explore the biblical theme of justice and discover how it's deeply rooted in the storyline of the Bible that leads to Jesus.

Exile

Exile is one of the core, yet often overlooked, themes underlying the entire biblical storyline. In this video, we'll see how Israel's exile to Babylon is a picture of all humanity's exile from Eden. We are all exiles longing for home, and Jesus is the one to open the way back to our true home and the fullness of relationship with God.

The Way of the Exile

If followers of Jesus are to give their total allegiance to God’s Kingdom, how should they relate to the governments and power structures of their own day? The experience of Daniel and his friends in Babylonian exile offers wisdom for navigating this tension. Following Jesus in our modern age means learning how to live in the way of the exile.

Son of Man

If you thought Christ was Jesus’ last name or the title he gave himself, think again! The title Jesus most often used for himself is the Son of Man. But what does that mean? In this video, we’ll explore the meaning of this fascinating phrase and see how it invites us into the larger biblical story.

Temple

The biblical authors describe Israel’s temple as the place where God’s space and human space overlap. In fact, the whole biblical drama can be told as a story about God’s temple: God creates a cosmic temple and, in Jesus, takes up residence in his temple-world. By the end of the biblical story, all of creation has become God’s sacred temple.

Generosity

In the story of the Bible, God is depicted as a generous host who provides for the needs of his guests. However, humans live from a mindset of scarcity and hoard God’s many gifts. In this video, we explore God’s plan for overcoming our selfishness by giving the ultimate gift of himself in the person of Jesus.

Sabbath

The Bible opens with God creating an ordered world from chaos in six days before resting on the seventh day. This pattern of seven that ends with divine-human rest echoes throughout Scripture. Jesus embraces this theme in his mission to establish God’s Kingdom on Earth, where humanity and God will finally rest together.

Tree of Life

In the opening pages of the Bible, God gives humanity a gift that they quickly forfeit: eternal life that comes by eating from the tree of life. Sacred trees are a powerful symbol woven throughout Scripture, culminating in the dramatic climax of Jesus’ death. His crucifixion on a cross transforms a tree of death into a new tree of life for all humanity.

Water of Life

In the beginning of the Bible, God transforms a desolate wilderness into a garden through a stream that waters the ground and brings life wherever it goes. Water imagery continues to develop throughout the biblical story where we see wells, cisterns, rain, and rivers all become images of God’s creative power.

The Test

From the garden of Eden to the tempation of Jesus, the Bible shows a repeated theme of testing. Learn more about how God determines the loyalty and trust of his covenant partners as we explore the biblical theme of testing.

Eternal Life

Jesus offered people eternal life. But what does that mean? Explore the meaning of a phrase that invites us into God’s life now and in the age to come.

Blessing and Curse

“Blessing” is a religious-sounding word that we use a lot. We say, “Bless you!” after a sneeze, or that we’re “so blessed” when life is good. But what does blessing mean in the Bible? In this video, we trace the theme of blessing and curse in the Bible to see how Jesus defeats the curse and restores the blessing of life to creation.

The Last Will Be First

In the New Testament, Jesus is called the “firstborn,” a title of authority. While firstborns traditionally received inheritance and power in the ancient world, Jesus redefines this power. In his Kingdom, the last are first, and true authority comes through loving others, even our enemies.

Anointing

Explore an ancient practice that marks people and places as bridges between Heaven and Earth.

The City

Why does the Bible open with a garden as the ideal space but close with a heavenly city? Explore the surprising theme of the city in the Bible.

Chaos Dragon

In the ancient world, the sea dragon was a common symbol that represented death and chaos. But the story of the Bible begins with God demonstrating his power over all creatures. While both spiritual and human forces threaten to pull creation into disorder, Jesus defeats the darkness by trusting God to bring life out of death.