The Book of Romans

About

The book of Romans is one of the longest and most significant things written by the Apostle Paul, formerly known as Saul of Tarsus. Paul was a Jewish rabbi belonging to a group called the Pharisees, and he passionately devoted his life to observing the Torah of Moses and the traditions of Israel. He viewed Jesus and his followers as a threat to these traditions, so he persecuted them. His life was changed, however, when he had a radical encounter with the risen Jesus himself. Paul was commissioned to become an apostle for Jesus, an official representative to the world of non-Jewish people (or Gentiles).

As part of this new vocation, he started going by his Roman name, Paul, and he traveled about the ancient Roman empire telling people about the risen King Jesus. These new converts would form communities called churches, and Paul would occasionally write letters to these churches to foster their faith, address specific problems, or answer questions. The book of Romans is one of these letters written later in his career.

Background of the Book of Romans

We know from Acts 18:1-2 that the church in Rome had existed for some time and was made up of both Jewish and non-Jewish followers. The crisis for this church began when the Roman emperor Claudius expelled all of the Jewish people from Rome. About five years later, all those Jews, including many who followed Jesus, were allowed to return. When they did, they found a church that had become non-Jewish in its customs and practice. This culture clash created lots of tension, and by Paul’s day, the Roman church was divided. They disagreed about how to follow Jesus, debating about whether or not non-Jewish Christians should observe the Sabbath, eat kosher, be circumcised, and so on.

Paul wrote this letter to accomplish a few things. He wanted this divided community to become unified once again. For a practical purpose, he hoped that the Roman church could become a staging ground for his mission to go even further west, reaching to Spain. These tense circumstances motivated Paul to write out his fullest explanation of the Gospel, the good news that announces Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection.

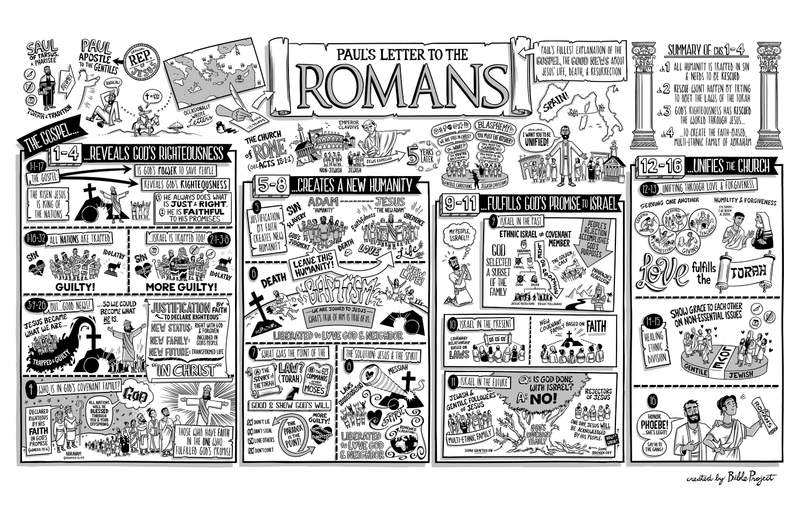

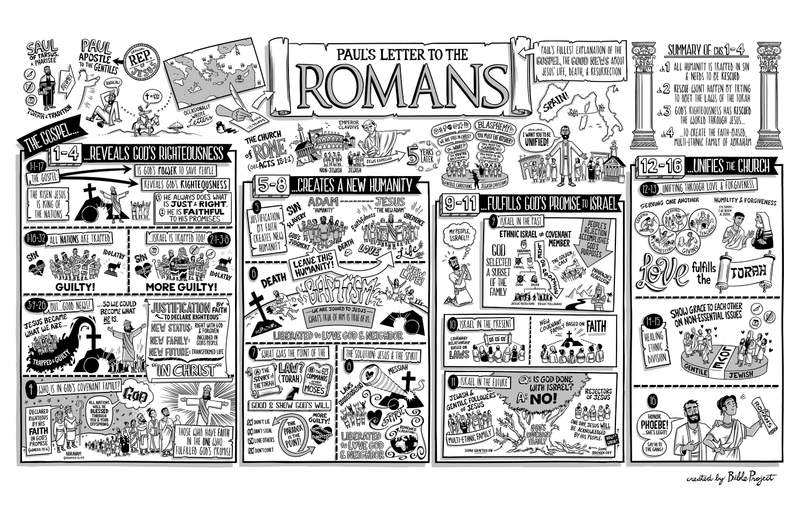

While the letter is designed to have four main movements, it is also unified as one long, flowing exploration of the Gospel, which “reveals God’s righteousness” (Rom. 1-4), “creates a new humanity” (Rom. 5-8), and “fulfills God’s promise to Israel” (Rom. 9-11). As a result, it is this Gospel alone that can “unify the Church” (Rom. 12-16).

Romans 1-4: The Gospel Reveals God’s Righteousness

Paul opens by introducing himself as an apostle appointed by God to spread the Gospel about Jesus (Rom. 1:1-17). This is the message announcing that Jesus is the Messiah of Israel, who was raised from the dead as the Son of God and King of the nations. As a result, Jesus now calls all humanity to come under his loving rule. Paul says that this good news about Jesus is God’s power to save people who trust in him and that it “reveals God’s righteousness.”

For Paul, “righteousness” is a rich word from the Hebrew Scriptures that describes God’s character. It means that God always acts in a way that is just and right and that God is faithful and just to fulfill his promises. Paul is saying that the story of Jesus shows how God has done both of these things.

In Romans 1:18-32, Paul goes into a long, creative retelling of Genesis 3-11, showing how the Gentile world, all nations, have become trapped in a spiral of sin and selfishness. The human heart and mind are broken. We’ve turned away from God to embrace idolatry, finding ultimate significance in created things and giving allegiance to things that are not God. This results in a distortion of our humanity and destructive behavior. What’s left is a humanity that stands guilty before a just and righteous God.

To this, Paul’s fellow Israelites might respond, “It’s a good thing God chose our people out from among the nations. He saved us out of slavery in Egypt and gave us the laws of the Torah, like observing the Sabbath, eating kosher,or circumcision. They all show us how to live as God’s holy people.”

Paul responds, “Not so fast!” He recalls the story of the Torah and the rest of the Old Testament, which showed that Israel was just as sinful, idolatrous, and morally broken as the rest of humanity. In fact, Israel is actually more guilty than the Gentiles because they have the Torah and should know better.

As our representative, Jesus took into himself the just consequences of all the pain, sin, and death humans have caused in the world, and he overcame it by his resurrection from the dead. It’s Jesus’ new life that is now made available to others. Jesus became what we are, so that we might become what he is. All of this, Paul says, is how God justifies those who trust or have faith in Jesus.

Justification is another rich Old Testament term for Paul, and it is related to God’s righteousness. It literally means “to declare righteous.” Because of what Jesus did on our behalf, we are given a new status before God. Instead of being found guilty, God declares that a person is in right relationship with him and forgiven. This results in a new family, as a person who trusts Jesus is given a place among God’s covenant people. Justification also results in a new future, which begins a journey of life transformation by God’s grace. All of these realities about justification are God’s gift to those who are in Christ because of their faith and loyalty to him.

In chapter 4, Paul explores the huge implications that all this has for those who can now be part of God’s covenant family. He turns to the story of Abraham in Genesis 15. Before the laws of the Torah were ever given to Israel, Abraham was justified, or declared righteous, before God. God promised that Abraham would become the father of a large, multiethnic family that would receive his blessing. However, Abraham and Sarah were very old and had never been able to have children. Nonetheless, Abraham had radical faith and trust in God’s promise, and God declared him to be righteous (Gen. 15:6). Paul’s claim is that Abraham’s multiethnic family is now becoming a reality through Jesus and his followers. Abraham’s descendants are spreading throughout the world, made up of Jews and Gentiles who have faith in the one who fulfilled God’s promises to Abraham, Jesus the Messiah.

Before we move on to chapters 5-16, let’s pause to summarize Paul’s main ideas in chapters 1-4 because they’re the foundation for understanding the rest of the letter. All of humanity is hopelessly trapped in sin and needs to be rescued, but that rescue will not happen by people trying to obey the laws of the Torah. God’s righteous character has moved him to rescue the world through Jesus’ death and resurrection, enabling the creation of a multiethnic family as his people.

Now Paul will go on to show how this new family is part of a much bigger story that is calling them to a totally new way of life.

Romans 5-8: The Gospel Creates a New Humanity

After showing how Jesus is forming a new covenant family of people from all nations, Paul goes on to claim that these people are the new humanity that fulfills God’s promises to ancient Israel by obeying the Torah in the power of the Spirit.

Paul begins by exploring how Jesus’ family is a new kind of humanity (Rom. 5). He looks back at the first human character in the biblical story, Adam, whose name means “humanity.” Adam and all humanity have chosen sin and selfishness, and as a consequence, they face God’s judgment. They’ve become enslaved to sin’s influence, resulting in death. Paul then contrasts Adam with Jesus, the “new Adam,” a human who lived in faithful obedience to God through his act of sacrificial love. Jesus offers his life as a gift to others so that they can be justified before God. And now Jesus stands as the head of a new humanity that is being transformed by the very same gift.

This leads right into chapter 6, where Paul reminds the Christians in Rome that choosing to follow Jesus means leaving their old Adam-like humanity behind and entering into the new Jesus-style humanity. And the sacred physical symbol of that transition was the immersion of their baptism. Their old humanity died with Jesus as they entered the water, but their new humanity was raised with him from the dead as they came up out of the water. When a person trusts in Jesus, their life is joined to his, and what’s true of him becomes true of them. It’s when people accept their identity as new Jesus-like humans that they are liberated to become wholehearted people who can love God and their neighbor.

Now, if creating this new humanity was always God’s purpose, then, Paul asks in chapter 7, what was the point of God giving Israel the law, or, in Hebrew, the Torah? Paul says that the commands in the Torah were good and showed God’s will for how Israel should live. However, if you read the storyline of the Torah, Israel broke all of its commands.

The more laws Israel received, the more they replayed the sin of Adam in rebellion. Even when God gave the people specific rules to obey, it didn’t fix the problem of the sinful human heart. So, paradoxically, the laws of the Torah made Israel even more guilty. But Paul says that paradox was the very point. God’s goal was to make it crystal clear that evil had hijacked the human heart, and the Torah, as good as it was, couldn’t do a thing about it.

In chapter 8, however, Paul says that the solution has arrived through Jesus and the Spirit. The commands of the Torah had acted like a magnifying glass, focusing the problem of the human condition in one place, Israel. But now Israel’s representative, Jesus the Messiah, has paid for and dealt with all that sin through his death and resurrection. He has released his Spirit into his new family to transform their hearts so that they can truly fulfill the ultimate call of all of the Torah’s commands—to love God and neighbor. God’s renewal of human beings is the first step in his larger mission to rescue and renew all creation, making it into a place where his love gets the final word.

While chapters 1-8 explain how God’s eternal purpose was fulfilled through Jesus, we’re still left with the question of the status of the Israelites who don’t acknowledge Jesus as their Messiah. How does this story fulfill God’s ancient promises to them?

Romans 9-11: The Gospel Fulfills God’s Promise to Israel

Paul begins chapter 9 with his own anguish over fellow Israelites who don’t think Jesus is their Messiah. Then he reflects on the Israel of the past and the Old Testament. He reminds us that simply being an ethnic Israelite, a physical descendant of Abraham, has never automatically made a person a faithful member of his covenant family. Paul shows us how God has always selected a subset from Abraham’s family line to carry on the line of promise. His point is that the line of promise is carried on by those who follow Jesus. He reminds us that for a long time, people inside and outside Abraham’s family have rejected God’s will. Paul recalls the story of Israel and the golden calf as well as Pharaoh’s rebellion, showing how God was able to orchestrate events so that the people’s rejection actually accomplished his own redemptive purposes.

In chapter 10, Paul turns his focus to the Israel of the present. The reason so many Israelites reject Jesus is that they’re basing their covenant relationship with God on their performance of the commands of the Torah. Sadly, they don’t recognize what God has done through Jesus to create the new covenant family.

In chapter 11, Paul asks about Israel in the future. Will God write his own people off? Paul says no. There are many Jewish people, including himself, who have recognized Jesus as the Messiah, but there are also a lot who haven’t. Once again, God has used this rejection for his own purposes, as it has caused the Gospel to spread farther into the Gentile world, making the family of Abraham even larger and more multiethnic. Paul describes God’s covenant family as a big olive tree. The rejectors of Jesus are branches that have been broken off, while these Gentiles are like wild branches that have been grafted on. However, Paul does say that one day Jesus will be acknowledged by his own people. He doesn’t offer any details about how but simply trusts in God’s character and promises that he will not give up on his covenant people.

Romans 12-16: The Gospel Unifies the Church

These ideas transition into the final section of the book of Romans, chapters 12-16. Because of their faith in Jesus, both Jews and Gentiles are a part of Abraham’s family. This new humanity is being transformed by God’s Spirit and is fulfilling God’s ancient promises. The only reasonable response to this is for these Jewish and non-Jewish Christians to become a unified church community.

In chapters 12-13, Paul shows us that this unity comes from a commitment to love and forgiveness. Love will look like everyone using their diverse gifts and talents to serve one another. Unity also means having humility and forgiveness. When these different ethnic groups and cultures come together in Jesus, conflict is inevitable and can only be overcome through the hard work of forgiveness. All of this is how these believers show the greatest Christian virtue, love, which fulfills the Torah’s greatest commands to love God and neighbor.

Chapters 14-15 focus on the issues creating ethnic divisions in the church, specifically disputes about Jewish food laws and observing the Sabbath. Paul says that these practices don’t define who is in or out of Jesus’ family. If the people differ over these culturally important but nonessential issues, they need to respect each other’s differences. In this way, love is what heals and unifies Jesus’ family.

Paul closes his letter by first commending Phoebe, a key leader of the church in Cenchreae. She had the honor of carrying and likely reading this letter aloud to the Roman churches. Paul further concludes by greeting all the people that he hasn’t seen for a while.

All the pieces of this letter fit together into a profound masterpiece of Paul’s writing. It explained and served to spread the message of Jesus’ new covenant family in the 1st century, and it continues to do the same in our world today.