Sacrifice and Atonement

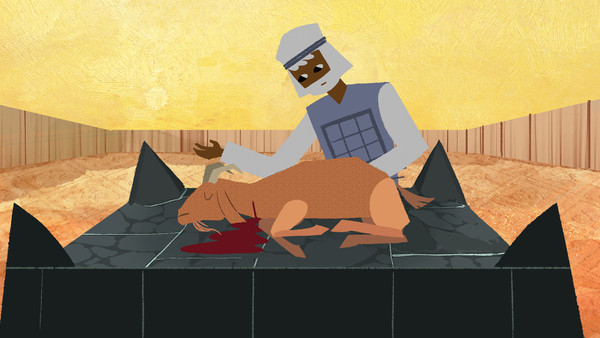

God is on a mission to remove evil from his good world, along with all of its corrosive effects. However, he wants to do it in a way that doesn’t involve removing humans. In this video, we trace the theme of God’s “covering” over human evil through animal sacrifices that ultimately point to Jesus and his death and resurrection.

Reflect

Imagine a world of peace, justice, and love. In a world like this, how would people communicate with one another? How would people spend time and money? How would authority figures use their power?

When people neglect to act with peace, justice, and love, it wreaks havoc—we call this evil. What is one way our relationships and the surrounding environment suffer from evil (e.g., Genesis 4:10-12, Romans 8:22-23)?

In order to heal this suffering, something first must be done to remove the evil. But what would happen if God removed everything contributing to the evil in the world? Would anyone remain alive? Discuss this predicament as a group and, if needed, review the video (0:22-1:07).

Discuss how God resolves this predicament through animal sacrifice and later through Jesus’ sacrifice. What does animal sacrifice represent? What is one way that Jesus is a more perfect sacrifice? Review the video or dive deeper by reading Hebrews 9:6-14.

Read Matthew 26:26-28. What is one practical way we can remember Jesus’ sacrifice? What is one specific way we can imitate Jesus’ sacrifice and repair relationships (e.g., John 15:9-13, Matthew 5:23-24, and Colossians 3:12-14)?

View Guide

Downloads

Biblical Themes

The Wilderness

Redemption

The Exodus Way

The Mountain

Heaven & Earth

The Messiah

The Covenants

Holiness

Sacrifice and Atonement

The Law

Gospel of the Kingdom

Image of God

Day of the Lord

Holy Spirit

Public Reading of Scripture

Justice

Exile

The Way of the Exile

Son of Man

Temple

Generosity

Sabbath

Tree of Life

Water of Life

The Test

Eternal Life

Blessing and Curse

The Last Will Be First

Anointing

The City