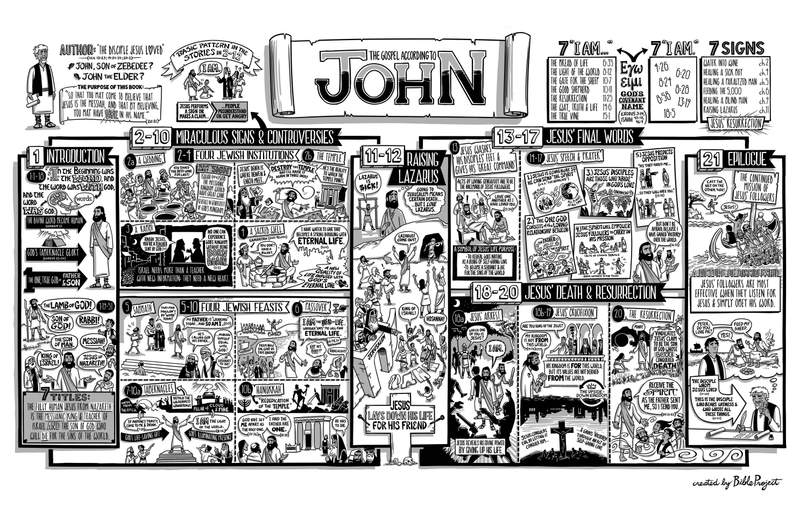

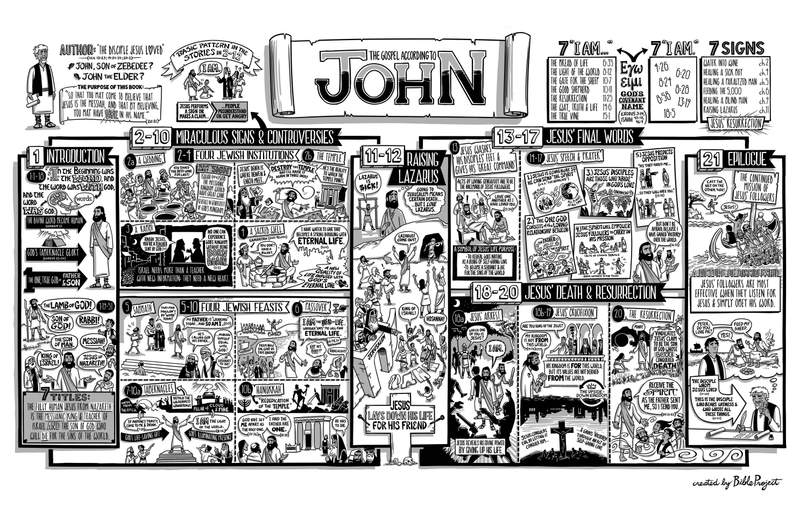

The Book of John

About

This is another one of the earliest accounts of Jesus’ life, and we learn at the end of the book that it comes from one of Jesus’ closest followers, called “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” He appears many times in the story itself (John 13:23; John 19:34-37; John 20:2), and there’s some debate about whether it’s John the son of Zebedee who was one of the twelve disciples, or a different John who lived in Jerusalem and was later known as John the Elder.

Whichever John it was, the book embodies his eyewitness testimony. It has been brilliantly designed with a clear purpose that he states near the end. He says he wrote the book, “so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, and that by believing, you may have life in his name” (John 20:31). John believes that the Jesus you read about in this book is alive and real and can change your life forever.

The book of John opens with an introductory poem and a short story (ch. 1) that is followed by a big block of stories about Jesus performing miraculous signs that generate increasing controversy (chs. 2-10). It all culminates in Jesus’ greatest sign, the raising of Lazarus, which also creates the greatest controversy. Israel’s leaders decide to kill Jesus (chs. 11-12), which launches us into the book’s second half in chapters 13-17. These chapters focus on Jesus’ final night and last words to his disciples, followed by his arrest, trial, death, and resurrection (chs. 18-20). The book concludes with an epilogue in chapter 21.

John 1: Jesus as the Word and the First Disciples

The first half of the book opens with a two-part introduction. First, there is a poem (John 1:1-18) that opens with the famous line, “In the beginning was the Word.” This is an obvious allusion to Genesis 1, when God created everything with his word. The image is powerful and profound. A person’s words are distinct from the person who speaks, yet they are also the embodiment of that person’s mind and will. John says that God’s Word was “with God,” that is, distinct, but also “the Word was God,” that is, divine. As we ponder this, we hear later in the poem that this divine Word became human as Jesus. John draws on the stories from Exodus 33-34, saying that Jesus is God’s tabernacle in our midst. The glorious, divine presence that hovered over the ark of the covenant became a human, Jesus. This leads us to his last claim that the one true God of Israel consists of God the Father and the Son, who has become human to reveal the Father to us.

As we consider these mind-bending claims, we next read the stories about how John the Baptist meets Jesus and then leads others to meet him and become his disciples. One by one as people encounter Jesus, they say out loud who they think he is. In this one chapter, Jesus is given seven titles: the Lamb of God, Son of God, Rabbi, Messiah, King of Israel, Jesus of Nazareth, and the Son of Man. These prepare us for John’s love of sevens in designing the story, which altogether make a claim that this fully human Jesus from Nazareth is the messianic King and teacher of Israel and that he’s the Son of God who will die for the sins of the world.

John 2-12: Jesus Performs Miraculous Signs

Now, that’s a big claim to make about someone, but John will support it through the stories in chapters 2-12. They all follow the same basic pattern. Jesus performs a sign or makes a claim about his divine identity, resulting in misunderstanding or controversy, and in the end, people are forced to make a choice about who they think Jesus is.

Chapters 2-4 show Jesus encountering four classic Jewish institutions, and, in each case, Jesus shows how he is the reality to which that institution points. Jesus is first placed at a wedding party where the wine runs out. Jesus takes huge jars of water, totaling about 120 gallons, and he turns them into the best wine ever. The head waiter then says to the groom, “You saved the best wine for last!” While this is true on a literal level, John also calls this miracle a sign (John 2:11). It’s a symbol that reveals something about Jesus. Just as Isaiah had said, the Messiah’s Kingdom would be like a huge party with good wine (Isa. 25:6-8). This first miraculous sign reveals the generosity of Jesus’ Kingdom.

Next, Jesus goes to the Jerusalem temple, the place where Heaven and Earth were supposed to come together. This is where God meets with his people. Jesus marches in and asserts his authority over the temple, running out all the money changers and stopping the sacrificial offerings. When he is threatened for this behavior, Jesus responds by saying, “Destroy this temple and I’ll raise it again in three days.” In other words, Jesus is claiming that his coming sacrificial death is where Heaven and Earth will truly meet. He is the reality to which the temple building points.

In chapter 3, Jesus has an all-night conversation with a rabbi named Nicodemus, who thinks that Jesus is just like him, another rabbi or teacher of Israel. Jesus tells him that Israel needs more than just another teacher with new information. They need a new heart and life, or in Jesus’ words, “No one can experience God’s Kingdom without being born again” (John 3:3). He believes that humans are caught in a web of selfishness and sin leading to death, but he knows that God loves this world and is here to offer people a new birth and a chance for a new life.

From there, Jesus travels north and ends up at a sacred well in conversation with a Samaritan, or non-Jewish, woman (ch. 4). They start talking about water, which Jesus turns into a metaphor of himself; he’s here to bring living water that can become a source of eternal life. In the book of John, this important phrase refers to a new quality of life, one that is infused with God’s eternal love, beginning now and lasting into the future.

The book of John continues from here with another collection of stories in chapters 5-10. These chapters take place during four Jewish sacred days or feasts. Once again, Jesus uses images related to the feasts to make claims about himself.

In chapter 5, Jesus heals a paralyzed man on the Sabbath, starting a controversy with the Jewish leaders about working on the day of rest. Jesus says that his Father is working on the Sabbath, and so is he. They catch his meaning. He was “calling God his Father, making himself equal with God” (John 5:17-18), and they want to kill him for this claim.

Chapter 6 takes place during Passover, the feast that retells the Exodus story with a symbolic meal of lamb, bread, and wine. On this occasion, Jesus miraculously provides food for a crowd of thousands. This results in people asking him for more bread, and Jesus responds by saying that he is the “true bread,” and that if they “eat” him, they will discover eternal life. This offends many people, who all stop following him.

Chapters 7-10 make up a block of stories set in Jerusalem during the Feast of Tabernacles. This festival retold the story of Israel’s wilderness wanderings as God guided them with the pillar of cloud and fire and provided them with water in the desert. Jesus stands in the temple courts and shouts, “If anyone is thirsty, let them come to me and drink” (John 7:37). Later, he says, “I am the light of the world” (John 8:12). In both of these announcements, Jesus is claiming to be the illuminating presence of God as well as the lifesaving gift of God to his people. While some people believe and follow him, others are offended and try to kill him for his exalted claims (John 8:59).

The final feast story, also told in chapter 10, takes place during Hanukkah, which means “rededication.” This festival retells the story of Judah Maccabee clearing the temple of idols and setting it apart as holy once more. Jesus enters into the temple area and says that he is the one whom God has “set apart as the holy one” (John 10:36). His point is that he is the true temple where God’s presence dwells, which is why he finally says, “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). This makes the Jerusalem leaders even more angry, and they set in motion a plan to kill Jesus, who retreats from the city.

All these conflicts culminate in one last miraculous sign in chapter 11. Jesus hears that his dear friend Lazarus is sick, but his family lives near Jerusalem. That city is now a death trap for Jesus. He could stay away and save his own life, but he loves Lazarus. Once Jesus hears that Lazarus has died, he goes to raise him from the dead. Jesus calls him back to life and out of his tomb, knowing that it will cost him his life. The news of this amazing sign spreads quickly, and, just as Jesus knew would happen, the Jerusalem leaders hear about it and conspire to murder him. Jesus rides into Jerusalem as Israel’s King, who is rejected by their leaders.

The first half of John draws to a close with this story about Jesus laying down his life as an act of love for a friend. This is, of course, yet another sign pointing forward to the cross. In this way, the story of Lazarus concludes the stories about Jesus’ signs and transitions the reader into the second half of the book.

John 13-17: Jesus’ Last Night With His Disciples

The second half of the book of John begins with chapters 13-17, and it focuses entirely on Jesus’ final night and last words to his disciples. He tries to prepare them for his coming death, and he starts by performing a shocking act at dinner (ch. 13). Jesus takes on the role of a common servant by kneeling down to wash the disciples’ dirty feet. In their culture, a superior rabbi would never do this kind of thing for his disciples. Jesus says this act is a symbol of his entire life’s purpose, which is to reveal God’s true nature as a being of self-giving love. It also symbolizes what it means for Jesus to be the messianic King. He will become a servant and give up his life to die for the sins of the world.

This leads to Jesus’ great command to his disciples. To follow Jesus is to love other people just as Jesus loved them. Acts of loving generosity are to be the hallmark of Jesus’ followers because this is what shows the world who Jesus is and, therefore, who God is.

Jesus continues with a long, flowing speech, concluded with a prayer (chs. 14-17). In these speeches, you’ll find a handful of repeated themes. Jesus keeps saying that he’ll be “going away.” This saddens the disciples, but Jesus also says that it’s for the best because it means that he will send the Spirit, also called “the advocate.” As a human, Jesus can only be in one place at a time, but the Spirit can be Jesus’ divine, personal presence in any place and any time.

Remember, for John, the unique deity of the one God consists of the loving, unified relationship shared between the Father and the Son. Jesus says the Spirit is that loving personal presence, which comes to live in his people and draw them into the love of the Father and the Son. Jesus says that his disciples are those who “abide” or “remain” in that divine love in the same way that branches are connected to a vine. He’s describing how the personal love of God can permeate a person’s life, healing, transforming, and making them new.

The Spirit will also empower Jesus’ followers to carry on his mission in the world and fulfill the great command to love others through radical acts of service. In this way, Jesus says, his disciples will “bear witness to the truth.” The Spirit will enable them to expose the selfish, corrupt ways we humans treat each other and declare that, in Jesus, God has saved the world through his love and opened up a new way to be human.

Finally, Jesus predicts that there will be opposition. Just as the Jewish leaders rejected him, his followers will also be persecuted. Jesus tells them not to be afraid because he has already conquered, or gained victory over, the world (John 16:33). Now, what Jesus means by the word “victory” he doesn’t really say, but it does lead us into the next section of the book, chapters 18-20. These chapters are where John shows us what victory looks like to Jesus.

John 18-20: Arrest, Trial, Crucifixion, and Resurrection

The Jewish leaders send soldiers to arrest Jesus, and they find him and his disciples in a garden. When they ask which one is Jesus, he declares, “I am,” and they fall backward. This is brilliant writing on John’s part. These words of Jesus are the culmination of two sets of seven instances in which Jesus has used that very phrase, highlighting one of John’s core claims about Jesus.

The words, “I am” (ego eimi in Greek), are the Greek translation of the personal covenant name of God that was revealed to Moses in Exodus 3 and repeated many times in Isaiah. John has strategically placed seven moments in the story where Jesus says “I am,” followed by an astounding claim: I am the bread of life; the light of the world; the gate for the sheep; the good shepherd; the resurrection; the way, the truth, and the life; and the true vine. John has also designed seven other stories that have key moments where Jesus simply says, “I am,” echoing the divine name. This occurrence as Jesus is arrested is the ironic climax of them all. The moment when Jesus most fully reveals his divine power and victory is the moment he gives up his life.

Jesus is put on trial for his exalted claims of being the Son of God and the King of Israel. He’s first tried before Israel’s high priest and later before the Roman governor Pilate, who has to take seriously anyone charged with claiming to be the king of Israel. Jesus tells Pilate that “my Kingdom is not from this world,” meaning that while he is a King and that his Kingdom is for this world, its radically different value system and definition of power and greatness are not derived from this world. The values of Jesus’ Kingdom are defined by God’s character and revealed through Jesus’ death on the cross. The world’s true King conquers sin and evil by letting it conquer him. He gains victory over the world through an act of self-giving love.

After Jesus’ body is placed in a sealed tomb, chapter 20 begins on the first day of the new week. Mary and then other disciples discover that Jesus’ tomb is strangely open and empty. Mary suddenly meets Jesus, who is alive and raised from the dead!

Now, pause for a moment. The resurrection of Jesus connects into another pattern of sevens in John’s gospel. Back at the wedding party, when Jesus changed water into wine, John said that it was Jesus’ first sign. John also identified the healing of the sick boy from chapter 4 as the second sign, letting you keep count of the rest. If you do, you’ll realize that the sixth sign was raising Lazarus from the tomb, which Jesus performed at the cost of his own life. This means that the seventh and final sign is the greatest—Jesus’ own resurrection from the dead. It vindicates Jesus’ claim to be the Son of God, the author of all life, whose love conquered death itself.

After the discovery of the empty tomb, Jesus meets up with the disciples and commissions them by sending the Spirit as he promised, so that his mission from the Father can now be carried on through them.

John 21: Peter’s Commission and the Disciple Whom Jesus Loved

The book of John then concludes with an epilogue exploring the ongoing mission of Jesus’ disciples (ch. 21). A number of disciples are fishing but catching nothing. Jesus appears to them on the shore, telling them to cast their net on the other side of the boat. When they obey him, they catch a huge amount of fish, and only in that moment do they recognize him. John is offering this story as a picture of discipleship to Jesus. His followers will be most effective in the world when their focus is not on their work but on listening for Jesus’ voice and obeying his words. That’s when they will truly see him at work in their lives.

Jesus next questions Peter and commissions him as a unique leader in the Jesus movement. Jesus indicates that Peter will also give up his life one day in service to Jesus. Then, all of a sudden, the story shifts focus to another figure standing there with Peter, the disciple whom Jesus loved. This is none other than the book’s author, John, and Jesus says his role in leading the Church will not be like Peter’s. John is called to spend his long life bearing witness to Jesus, so that others may believe in him.

And that is exactly what he did as he authored this amazing story about Jesus the Messiah and Son of God.