The Book of 2 Thessalonians

About

Not long after Paul wrote 1 Thessalonians, he got another report about the Christians in Thessalonica. The problems he had addressed in his first letter had not only continued but had gotten worse. The persecutions had intensified, and the Thessalonian Christians were confused and scared about the return of Jesus.

Paul sent off 2 Thessalonians, which is designed with three sections that address three issues within the church. In chapter 1, Paul offers hope in the midst of continued persecution. In chapter 2, he offers more clarity about the coming Day of the Lord. And in chapter 3, Paul gives a specific challenge to the idle people who were refusing to work normal jobs. The end to each of these sections is clearly marked by a short closing prayer (2 Thess. 1:11-12; 2:16-17; 3:16-18).

2 Thessalonians 1: Hope in Persecution

Paul opens with a thanksgiving prayer for the Thessalonians’ continued faithfulness and love, specifically for their endurance (2 Thess. 1:1-3). He has learned that their Greek and Roman neighbors have intensified the persecution of Christians. They’re a religious minority facing violent oppression, and Paul worries that they might give up on Jesus if things get worse. Paul reminds them, as he did in the first letter, that suffering because you’re associated with Jesus is actually a way of participating in God’s Kingdom (2 Thess. 1:4-12). Jesus was inaugurated as King through the suffering of the cross, so his followers can show their own victory over the world by imitating Jesus’ nonviolence and patient endurance.

Paul also reminds them that this persecution won’t last forever. When Jesus returns, he will bring justice to those who have oppressed people and shed innocent blood. More specifically, Paul says that their punishment is to be banished “away from the face of the Lord and from the glory of his power” (2 Thess. 1:9). Paul doesn’t speculate on the fate of those who reject Jesus except to say that, throughout their lives, they had wanted nothing to do with Jesus, and in the end they get what they want—relational distance from their Creator and King. For Paul, this is the ultimate tragedy. To choose separation from Jesus, who is the source of all love and life, is to embrace one’s own undoing. He closes this thought by praying that God would use their suffering to bring about deep character change inside them so that their lives may bring honor to the name of Jesus (2 Thess. 1:11-12).

2 Thessalonians 2: Day of the Lord

In chapter 2, Paul moves on to address a specific issue related to the return of Jesus and the Day of the Lord. Someone in the Thessalonian church community had been spreading wrong information in Paul’s name, saying that God’s final act of justice on human evil, the Day of the Lord, was upon them. According to them, judgment day had come. These people had likely been predicting dates for the end of all things and were frightening other Christians. Given the difficult circumstances of the Thessalonians, you can see why this would cause some concern. They were afraid for their lives and vulnerable to someone claiming that Jesus had already returned “like a thief in the night,” as Paul described in his first letter (1 Thes. 5:2). Maybe God had abandoned them to their suffering.

This really upsets Paul because his letter is being grossly misrepresented. The return of Jesus should inspire hope and confidence, not fear! He reminds them of all he had taught about Jesus’ return when he was still in town, leaving here only a short summary. In fact, it’s a little too short, and the paragraph has many puzzles and problems with interpretation. What is clear is that Paul cites a well-known theme from Isaiah 13-14 and Daniel 7-12.

The kingdoms of the world will continue to produce rulers who rebel against God, like Nebuchadnezzar or the king of the North. These leaders exalted themselves to divine authority and sowed the seeds of their destruction. For Paul, the prophecies about these ancient kings show a pattern, which he saw fulfilled in his own day with the Roman emperors Caligula and Nero, and which he expected to see repeated again. History will repeat itself, eventually culminating with a rebellious ruler, empowered by evil itself, who will wreak violence and havoc in God’s world—but not forever. When Jesus returns, he will confront “the rebel” and all those who perpetrate evil, delivering his people.

Paul’s point here was not to give later readers fuel for apocalyptic speculation. Rather, he’s trying to comfort the Thessalonians by recalling the teaching of Jesus, who said that the events leading up to his return will be very public and obvious (Mark 13). In other words, they don’t need to be scared or worried that they’ve been abandoned, but they do need to stay faithful until Jesus returns to deliver them. In his closing prayer (2 Thess. 2:16-17), Paul asks Jesus and the Father to comfort and strengthen the Thessalonians so that they may stay devoted to the way of Jesus.

2 Thessalonians 3: A Challenge to the Idle

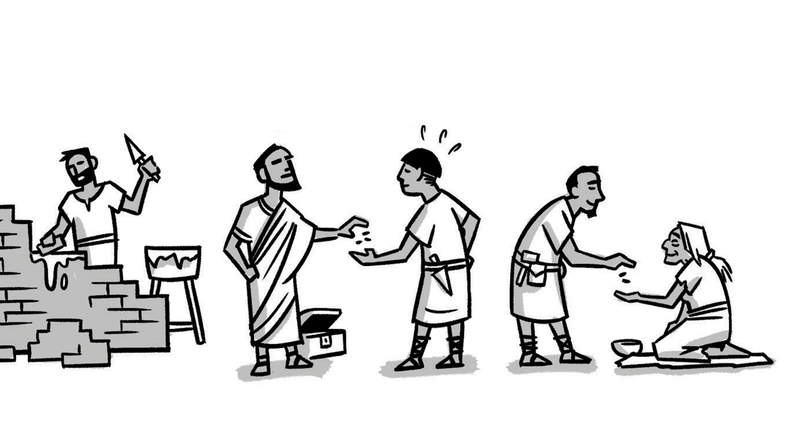

This brings us to the final topic, a challenge for the people who were “idle” (2 Thess. 3:1-15). This term doesn’t mean that they were simply lazy. It refers to the people that were irresponsible, refusing to work or to provide for themselves, resulting in chaotic personal lives. Paul had addressed this problem in his first letter (1 Thess. 4:10-12 and 5:14), but it appears to have gotten worse.

We don’t know for certain why some people were refusing to work. It’s possible that this issue was connected to the previous one. Maybe some people thought Jesus would return soon and, as a result, quit their jobs and dropped out of normal life. However, it’s more likely that this problem is related to a practice in Roman culture called patronage. Poorer people in cities would become clients, kind of like personal assistants, to wealthy people and live off of their generosity with many strings attached. This often forced the clients to participate in their patron’s morally corrupt way of life, not to mention that it was an unstable source of income. This is what Paul refers to as “leading a disordered life, not working, but meddling in the business of others” (2 Thess. 3:11).

Paul reminds them of the example he set when he was with them. He didn’t ask for their support, but he worked a manual labor job to provide for himself so that he could serve the Thessalonians free of charge. This is the ideal he’s promoting. A follower of Jesus should imitate the Lord’s self-giving love by working hard, providing for themselves, and acting as a benefit to others. Paul concludes with a final prayer, asking that in the midst of all their confusion and suffering, God would grant them peace through the Lord Jesus, the Messiah.

This short letter to the Thessalonians helps us to see that the early Christian belief in Jesus’ return and the hope of final justice were not meant to generate speculation about apocalyptic timelines. Rather, these beliefs were supposed to bring hope to inspire faithfulness and devotion to Jesus. This was especially true for persecuted Christians facing violent opposition.

For later generations of Christians, whether they undergo persecution or not, this letter reminds us that what you hope for shapes what you live for.