The Book of Matthew

About

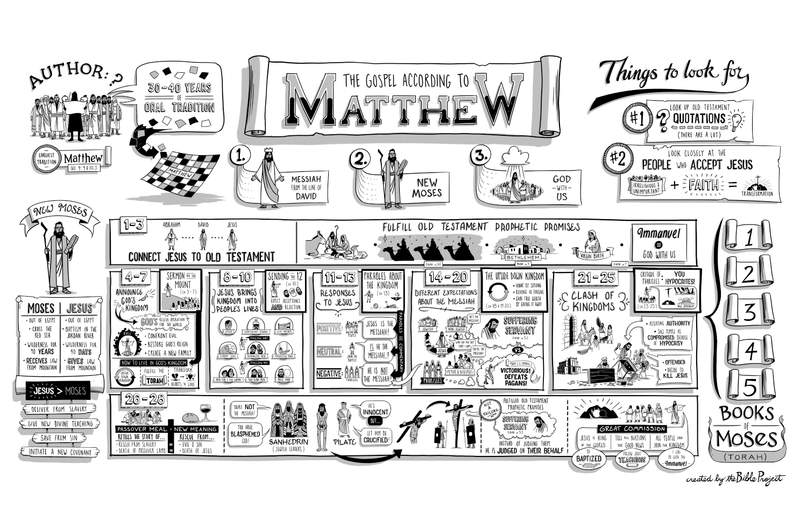

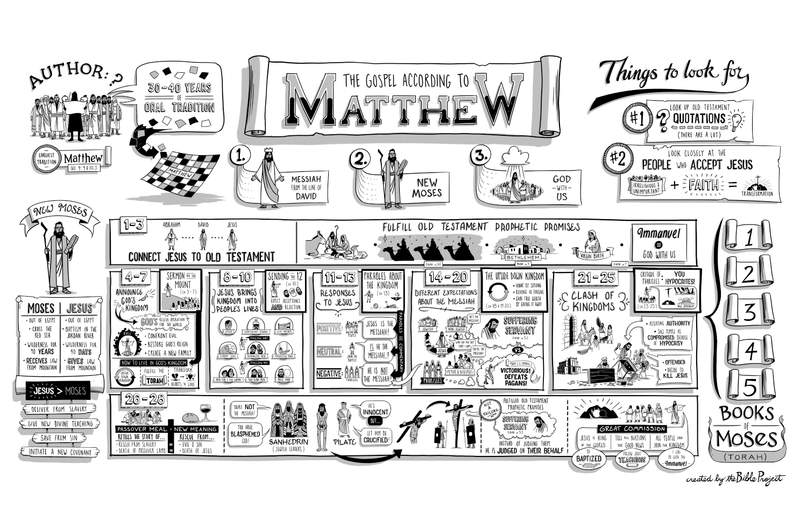

This is one of the earliest official accounts of Jesus of Nazareth. While the book itself is anonymous, the earliest reliable tradition links it to Matthew the tax collector, one of the twelve apostles that Jesus appointed, who appears in the book himself (Matt. 9:9; Matt. 10:3). For about 30-40 years, the apostles orally taught and passed on their eyewitness accounts of Jesus along with his teachings that they had memorized. Matthew has collected and arranged all those into an amazing tapestry and designed his account to highlight certain themes about Jesus.

Matthew wanted to show how Jesus is the continuation and fulfillment of the whole biblical story of God and Israel, so he emphasizes that:

- Jesus is the Messiah from the line of David

- Jesus is a new, authoritative teacher like Moses

- Jesus is God with us, or in Hebrew, Immanuel

The book of Matthew has been designed with an introduction and a conclusion that act as a frame around five clear sections in the center. Each of those sections concludes with a long block of Jesus’ teaching.

Matthew 1-3: Jesus as the Messiah and Immanuel (God With Us)

Chapters 1-3 set the stage by attaching Jesus’ story right onto the Old Testament Scriptures. Matthew opens with a genealogy of Jesus that highlights him as the messianic son of David and the son of Abraham who will bring God’s blessing to all of the nations. After that, we come to the famous story about Jesus’ birth and how it fulfilled the Old Testament prophetic promises about how the nations would come to honor the Messiah who was born in Bethlehem. More than that, Jesus’ conception was by the Holy Spirit, and he was named Immanuel, which amounts to a claim that Jesus is no mere human. He is God with us, the God of Israel embodied as a human.

You can see right away two of Matthew’s key themes in the introduction (Jesus is the Messiah and God with us), but Matthew also wants to show how Jesus is like a new Moses. Like Moses, Jesus came up out of Egypt (ch. 2), passed through the waters of baptism (ch. 3), entered the wilderness for 40 days (ch. 4), and went up onto a mountain to give new teaching, most of which focused on the Torah (chs. 5-7). Matthew is claiming that Jesus is the promised greater-than-Moses figure, who will deliver Israel from slavery, give them new divine teaching, save them from their sins, and initiate a new covenant relationship between God and his people. This also explains why Matthew structured the center of the book into five main parts that highlight Jesus’ teaching. He created a parallel to the five books of Moses, presenting Jesus as Israel’s new, authoritative teacher who will fulfill the storyline of the Torah.

Matthew 4-7: Arrival of God’s Kingdom and the Sermon on the Mount

In the first main section (chs. 4-7), Jesus steps onto the scene announcing the arrival of God’s Kingdom. This is really important because the Kingdom is the main theme of Jesus’ teaching. In essence, it’s about God’s rescue operation for his world, all taking place through King Jesus. He has come to confront evil, especially spiritual evil and its legacy of demonization, disease, and death. He is here to restore God’s reign over the world by creating a new family of people who will live under his rule.

After Jesus begins healing people and forming a movement, he takes his followers to a mountain and delivers his first block of teaching, traditionally called the Sermon on the Mount (chs. 5-7). Here, Jesus explores what it looks like to follow him and live in God’s Kingdom. It’s an Upside-Down Kingdom where there are no privileged members—the poor, the nobodies, the wealthy, the religious, everyone is invited to turn and follow Jesus and join his new family. Jesus makes clear that he’s not here to set aside the commands of the Torah but rather to fulfill them through his teachings, which transform the hearts of his people to truly love God and their neighbor, including their enemies.

Matthew 8-10: The Kingdom’s Power and Invitation to Discipleship

After concluding his great teaching on the Kingdom, the next section shows Jesus bringing the Kingdom into reality in the day-to-day lives of people (chs. 8-10). Matthew has arranged nine stories in which Jesus brings the liberating power of God’s Kingdom to bear on the lives of normal people. There are three groups of three stories here, all about people who are sick, broken, or in danger. Jesus heals or saves all of them by acts of power. Then, in between the triads, we find two parallel stories about Jesus’ radical call to follow him. A person can only enter God’s Kingdom by following him and becoming his disciple.

In chapter 10, we continue into the second large block of teaching in the book of Matthew, as Jesus extends his reach by sending out 12 disciples. He teaches these disciples how to announce the Kingdom of God as well as what to expect once they do. While many among Israel will accept the Kingdom of Jesus, Israel’s leaders stand to lose a lot if they repent. They will likely reject and persecute Jesus and his followers, and his followers should be ready for it.

Matthew 11-13: Different Reactions to Jesus

This leads into chapters 11-13, where Matthew has collected a group of stories about people responding to Jesus and his message. It’s a mixed bag. Some react positively; they love Jesus and recognize him as the Messiah. Others are neutral; they’re not sure what to make of Jesus. John the Baptist ends up in this group when he makes it clear that Jesus is not what he expected. The reactions of Israel’s leaders are negative, as the Pharisees and Bible teachers reject and challenge Jesus altogether. They think that he’s a false teacher leading the people astray, and they accuse him of blasphemy for his exalted claims of divine authority.

Jesus isn’t surprised or thrown by these diverse responses. In fact, he focuses on them in the third large block of teaching starting in chapter 13. Here, Matthew has collected many of Jesus’ parables about the Kingdom: the farmer throwing seed on four types of soil, the mustard seed, the pearl, and the buried treasure. These parables are like a commentary on the stories that you’ve just read. Some accept Jesus with enthusiasm, while others reject him, but God’s Kingdom will continue spreading despite these obstacles.

As we finish chapter 13, we are halfway through Matthew’s story of Jesus, and he’s raised the key questions about Jesus. How will this tension between Jesus and Israel’s leaders play itself out?

Matthew 14-20: What It Means for Jesus to Be the Messiah

In chapters 14-20, the next main section of the book, Matthew explores the different perspectives people had about what it meant for Jesus to be the Messiah. Jesus keeps healing sick people, and twice he miraculously provides food for huge crowds in the desert, one of which is made up of Jewish people (ch. 14), the other non-Jewish (ch. 15). This sign is very similar to what Moses did for Israel in the wilderness (Exod. 16), so lots of people become excited about Jesus and think that he’s the great prophet and Messiah.

The religious leaders, however, are not convinced. Their view of the messiah is centered and built on passages such as Psalm 2 or Daniel 2 about a victorious messiah who will deliver Israel and defeat the pagan oppressors. From their point of view, Jesus is a false teacher who’s making blasphemous claims about himself, so they increase their opposition and start hatching a plan to kill him.

In chapters 16 and 17, Jesus withdraws and teaches his closest disciples what it really means for him to be Israel’s Messiah, because it’s not what they expect. Jesus asks the disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” Peter comes up with the right answer: “You’re the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” It soon becomes clear, however, that Peter is thinking of a king who will reign victoriously through military power.

Jesus challenges Peter, saying that, yes, he will become king but in a different way. Jesus starts teaching on themes from the prophet Isaiah, who said that the messianic king would suffer and die for the sins of his people. Jesus was positioning himself as a messianic king who reigns by becoming a servant and laying down his life for Israel and the nations.

Peter and the disciples don’t really get it, so Jesus continues into the fourth large block of teaching in chapter 18, followed by another series of teachings in chapters 19 and 20. These are all about the upside-down nature of Jesus’ messianic Kingdom and how it turns our normal value system on its head. In the community of the servant King, you gain honor by serving others. Instead of revenge, you forgive and do good to your enemies. You gain true wealth by giving it away. To follow the servant Messiah, you must become a servant yourself.

Matthew 21-25: Jesus Confronts Israel’s Leaders

In the next section (chs. 21-25), we watch the two kingdoms clash, Jesus’ Kingdom and that of Israel’s leaders. Jesus comes to Jerusalem for Passover, riding in on a donkey as the crowds hail him as the Messiah. Jesus immediately marches into the courtyard of the temple, creating a disruption that brings daily sacrifices to a halt. His actions speak louder than words. As Israel’s king, Jesus was asserting his royal authority over the temple, the place where God and Israel met together. In Jesus’ view, the temple was compromised by the hypocrisy of Israel’s leaders, so he challenged their authority. The leaders are deeply offended, and in chapter 22, they try to trap Jesus and shame him in public debate. They fail, and as a result, they determine to have him killed.

In response, Jesus delivers his final block of teaching (chs. 23-25). First, he offers a passionate critique of the Pharisees and their hypocrisy before weeping over Jerusalem and its rejection of God’s Kingdom. Jesus withdraws with the disciples and starts telling them what’s going to happen. These leaders are going to execute him, but in doing so, they will be creating their own demise. Instead of accepting Jesus' way of the peaceful Kingdom, they are going to take the road of revolt against Rome, so the city and the temple will be destroyed.

But, Jesus says, that’s not the end of the story. He will be vindicated after his death by his resurrection and one day return to set up his Kingdom over all nations. In the meantime, the disciples should stay alert and committed to announcing Jesus’ Kingdom and spreading the good news about him.

Matthew 26-28: Jesus’ Trial, Crucifixion, and Resurrection

With all of this ringing in the disciples’ ears, the story comes to its climax in chapters 26-28. That night, Jesus takes the disciples aside to celebrate a Passover meal, which retells the story of Israel’s rescue from slavery and the death of the Passover lamb. Jesus uses the bread and wine from the meal as new symbols, showing that his coming death would be a sacrifice that would redeem people from slavery, evil, and sin.

After the meal, Jesus is arrested and put on trial before the Sanhedrin, a council of Jewish leaders. His claim to be the Messiah is rejected, he’s charged with blasphemy against God, and he’s brought before the Roman governor Pilate. Pilate thinks that Jesus is innocent, but he gives in and sentences Jesus to death by crucifixion. Jesus is led away by the Roman soldiers and is crucified.

You’ll notice here that, just as in the opening chapters, there are lots of references to the Old Testament. Matthew is showing that Jesus’ death was not a failure but rather the surprising fulfillment of prophetic promises. Jesus came as the servant Messiah who was rejected by his own people. But instead of judging them, he is judged on their behalf and bears the consequences of their sin.

The crucifixion scene comes to a close and Jesus’ body is placed in a tomb, but the book of Matthew ends with a surprising twist. On Sunday morning, the disciples discover that the tomb is empty. Suddenly, all kinds of people begin to see Jesus risen from the dead.

The book concludes with the risen Jesus giving a final teaching called the Great Commission. He is now the true King of the world, so he sends the disciples to all nations with the good news that Jesus is Lord. Anyone can join his Kingdom by being baptized and following his teachings. Echoing all the way back to the first chapter with his name, Immanuel, or “God with us,” Jesus’ last words to his disciples are, “I will be with you.” It’s a promise of Jesus’ personal presence that will be with his followers until he finally returns to rejoin heaven and earth in God’s Kingdom.