The Exodus Way

Summary

In the story about God delivering Israelites from slavery in Egypt, a literary pattern emerges—an exodus pattern that authors repeat over and again throughout the biblical story. This pattern often involves God providing people with the way out of bondage or oppression, the way through a period of challenge or testing, and the way into new life.

The Big Picture

The Exodus Way Pattern

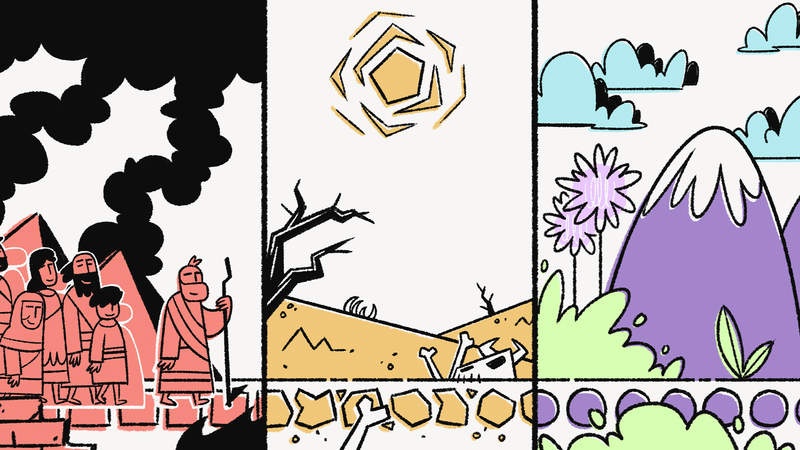

The exodus story involves an epic showdown between Pharaoh and Moses that includes 10 intense plagues, a massive group of escaping slaves who safely walk through the Red Sea’s chaotic waters, and freedom for Israel on the other side. But the story continues well beyond the showdown and escape to establish a three-part pattern we discover in Scripture so often that it becomes thematic. We’re calling this theme the exodus way—it’s the way out of slavery, the way through a wilderness transformation, and the way into the abundant life God offers in the promised land.

The exodus story begins when Pharaoh, a harsh Egyptian dictator, crushes the Israelites under the weight of oppressive slavery. After hearing the cries of his people, God sends Moses to rescue them. So Moses commands Pharaoh to let God’s people go. After Pharaoh refuses, he watches his kingdom crumble as all of Egypt suffers from things like heaps of invasive frogs, incurable bursting boils, and crop-destroying hailstorms.

As the Israelites march out of a defeated Egypt, they stop at what seems like a dead end: the chaotic waters of the Red Sea. But God provides a way through, parting the waters so that the Israelites can pass through on dry ground. This moment illustrates a recurring pattern for the way out of slavery—God guides his people along paths that look like death but ultimately lead to life.

Now free, the people follow God through the wilderness, which provides an opportunity for them to learn to trust God for food, water, and protection. In a harsh and barren wasteland, it’s easy to despair at the first sign of hunger and thirst. But God supplies food from the sky and water from a rock. The way through the wilderness requires increased faith and reliance on God. As God leads people through this experience, he seeks to transform them.

On the far side of the wilderness journey, the Israelites encounter the way into the promised land—a land flowing with milk and honey. Here the former slaves can roam free and enjoy God’s goodness and provision. The wasteland gives way to abundant harvest, so that the people can spread God’s blessing to their neighbors and the world. The way out of slavery, through the wilderness, and into the promised land provides a three-part pattern that other key events in the biblical story will follow, like a repeated melody.

Out, Through, and In—Again and Again

After settling in the promised land, the Israelites face a fresh crop of new Pharaohs, the rulers of neighboring nations, who oppress them. Again and again God rescues them by sending Moses-like figures called judges. They also lead the people out of slavery and into freedom while facing tests along the way. Like Moses and the Israelites, they are challenged to trust God to guide them through difficult situations. And when God brings them through the difficulties, he leads them into a time of peace in the land. We see the pattern on repeat, but then something shifts.

In a tragic reversal, Israel’s own kings begin to oppress their people. God has already warned them about the dire consequences sure to result from such rebellion, but his warnings are ignored as the oppression continues. So God allows a foreign enemy to remove Israel from the land. The king of Babylon—the greatest Pharaoh-like figure since the book of Exodus—conquers the Israelites and places the yoke of slavery back on their necks. He takes them on a backward journey along the exodus way: out of the good land, back through the wilderness, and into slavery once again.

Though exiled and oppressed, Israel still has reason to hope. Even in these bleak circumstances, God’s prophets imagine a way out of slavery. They speak of a new rescuer—a better Moses—who will again lead God’s people to freedom. Isaiah describes God leading his people out of exile on a highway through the wilderness as he makes the dangerous wasteland a safe and fertile path. And on the other side of that wilderness is something greater than the original promised land of Canaan. This new rescuer will lead the whole world on the way into a freedom and abundance that lasts forever.

Jesus Is the Way

The Israelites eventually return from exile to re-enter the promised land, but God’s promises of blessing and abundance have not yet been fully realized. So clinging to the prophets’ words, the people continue to wait for a new Moses. Then, one day, this rescuer shows up in a surprising place, as a baby lying in a manger in the little town of Bethlehem.

People hope that Jesus will rescue them from their oppression under Rome and the corruption of their own religious leaders. But he has his sights set on a much bigger, far more deadly “Pharaoh”—a merciless slave master called sin and death that captures and ensnares all humanity. Instead of wielding a sword or leading an army, Jesus walks humbly into the chaotic waters of death and destroys this last and greatest enemy, making a path to true freedom for anyone who wants to follow.

The first people to walk that path with Jesus call themselves followers of “The Way.” They enter the waters of baptism as a sign that they are following Jesus out of slavery to death, through the transforming wilderness experience of learning to trust God amidst the fear and uncertainty of this dark world, and into the restful peace God has promised. That place of peace involves both a new way of life with him and an entirely renewed cosmos, one no longer suffering under any form of oppression.

Jesus’ followers still endure corruption and death as they continue on the path through the wilderness. But God ultimately provides everything they need for this difficult journey. And they can walk confidently, knowing that Jesus’ path will one day lead them into the reunion of Heaven and Earth, where love, joy, and peace saturate every relationship.

So as a patterned literary theme, the exodus way extends well beyond Moses and Israel, reaching its climax in the story of Jesus and his followers. Jesus is the way out, the way through, and the way in.

Dive Deeper

So far we’ve just skimmed the surface. Explore these studies to take a deeper dive into how this theme contributes to the whole story of the Bible.

Read

12 Now the Lord said to Abram,

“Go from your country,

And from your relatives

And from your father’s house,

To the land which I will show you;

2 And I will make you into a great nation,

And I will bless you,

And make your name great;

And you shall be a blessing;

3 And I will bless those who bless you,

And the one who curses you I will curse.

And in you all the families of the earth will be blessed.”

4 So Abram went away as the Lord had spoken to him; and Lot went with him. Now Abram was seventy-five years old when he departed from Haran. 5 Abram took his wife Sarai and his nephew Lot, and all their possessions which they had accumulated, and the people which they had acquired in Haran, and they set out for the land of Canaan; so they came to the land of Canaan. 6 Abram passed through the land as far as the site of Shechem, to the oak of Moreh. Now the Canaanites were in the land at that time. 7 And the Lord appeared to Abram and said, “To your descendants I will give this land.” So he built an altar there to the Lord who had appeared to him. 8 Then he proceeded from there to the mountain on the east of Bethel, and pitched his tent with Bethel on the west and Ai on the east; and there he built an altar to the Lord and called upon the name of the Lord. 9 Then Abram journeyed on, continuing toward the Negev.10 Now there was a famine in the land; so Abram went down to Egypt to live there for a time, because the famine was severe in the land. 11 It came about, when he was approaching Egypt, that he said to his wife Sarai, “See now, I know that you are a beautiful woman; 12 and when the Egyptians see you, they will say, ‘This is his wife’; and they will kill me, but they will let you live. 13 Please say that you are my sister so that it may go well for me because of you, and that I may live on account of you.” 14 Now it came about, when Abram entered Egypt, that the Egyptians saw that the woman was very beautiful. 15 Pharaoh’s officials saw her and praised her to Pharaoh; and the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house. 16 Therefore he treated Abram well for her sake; and he gave him sheep, oxen, male donkeys, male servants and female servants, female donkeys, and camels.

17 But the Lord struck Pharaoh and his house with great plagues because of Sarai, Abram’s wife. 18 Then Pharaoh called Abram and said, “What is this that you have done to me? Why did you not tell me that she was your wife? 19 Why did you say, ‘She is my sister,’ so that I took her for myself as a wife? Now then, here is your wife, take her and go!” 20 And Pharaoh commanded his men concerning him; and they escorted him away, with his wife and all that belonged to him.

Consider

Our most common understanding of the exodus is probably Israel’s exodus from slavery in Egypt. But earlier in the biblical story, Abram (later Abraham) experiences his own exodus from Egypt, and this foreshadows Israel’s exodus.

In Genesis 12:1-9, God promises to bless Abram, to make him the father of a huge family (or “nation”), and to give his descendants a good land called Canaan. But soon after God makes the promise, a severe famine strikes, and Abram escapes to Egypt for provision and relief.

Because his wife Sarai (later Sarah) is very beautiful, Abram fears that the Egyptians might kill him to take Sarai. Now Abram could trust God’s protection here. But instead, he chooses to self-protect with deception and tells Sarai to claim to be his sister. So because Abram doesn’t trust in God’s protection and chooses deceit, Pharaoh believes Sarai is unmarried and takes her as his own wife. Then Pharaoh pays Abram a huge bride price, making Abram wealthy. It looks like his deception is proving beneficial all around.

Except there’s a massive problem now. How can the childless Abram become a great nation if he has no wife? Although Abram seems resigned to the loss of Sarai, God intervenes in order to fulfill his promises. God afflicts Pharaoh’s household with plagues, and this leads to Sarai’s liberation. An exodus is underway.

After summoning Abram to account for his actions, Pharaoh returns Sarai and sends them both away. So God gives Abram and Sarai a way out of danger in Egypt, a way through the wilderness, and a way into the promised land of Canaan, pointing toward the greater exodus to come.

Reflect

What does Abram and Sarai’s exodus reveal about how God acts, particularly when his promises are threatened?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

8 And the child grew and was weaned, and Abraham held a great feast on the day that Isaac was weaned.

9 Now Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had borne to Abraham, mocking Isaac. 10 Therefore she said to Abraham, “Drive out this slave woman and her son, for the son of this slave woman shall not be an heir with my son Isaac!” 11 The matter distressed Abraham greatly because of his son Ishmael. 12 But God said to Abraham, “Do not be distressed because of the boy and your slave woman; whatever Sarah tells you, listen to her, for through Isaac your descendants shall be named. 13 And of the son of the slave woman I will make a nation also, because he is your descendant.” 14 So Abraham got up early in the morning and took bread and a skin of water, and gave them to Hagar, putting them on her shoulder, and gave her the boy, and sent her away. And she departed and wandered about in the wilderness of Beersheba.

15 When the water in the skin was used up, she left the boy under one of the bushes. 16 Then she went and sat down opposite him, about a bowshot away, for she said, “May I not see the boy die!” And she sat opposite him, and raised her voice and wept. 17 God heard the boy crying; and the angel of God called to Hagar from heaven and said to her, “What is the matter with you, Hagar? Do not fear, for God has heard the voice of the boy where he is. 18 Get up, lift up the boy, and hold him by the hand, for I will make a great nation of him.” 19 Then God opened her eyes, and she saw a well of water; and she went and filled the skin with water and gave the boy a drink.

20 And God was with the boy, and he grew; and he lived in the wilderness and became an archer. 21 He lived in the wilderness of Paran, and his mother took a wife for him from the land of Egypt.

Consider

After their exodus from Egypt, Sarai remains unable to bear children, so she devises a sneaky workaround. She forces her female Egyptian slave, Hagar, to become another wife for Abram, hoping Hagar can serve as a surrogate mother and bear the child she so desperately desires. But when Hagar becomes pregnant, Sarai begins to “oppress” (Hebrew ‘anah) Hagar (Gen. 16:6), just as the Israelites are later enslaved and “oppressed” (‘anah) by the Egyptians (15:13; also Exod. 1:11-12).

So Hagar escapes into the wilderness where she encounters God. The exodus way in Scripture almost always involves some kind of escape into the wilderness. Even though the wilderness itself seems lifeless and threatening, it always proves to be a place where God meets and cares for people.

God tells Hagar to name her unborn son Ishmael, which means “God Hears.” The name is a reminder to Hagar that her cries for help are not going unnoticed—he hears her (Gen. 16:11). But God also tells her to return to her difficult situation within Abram’s household (v. 9) so she can receive the essential resources she’ll need to deliver and care for her baby.

Years later, Sarai (renamed Sarah) ends up having a son, Isaac. And she tells Abram (renamed Abraham) to kick Hagar and Ishmael out of their household so that Ishmael won’t compete with Isaac as Abraham’s heir. Although Abraham shows real concern for Ishmael, God still tells him to listen to his wife (Gen. 21:1-14).

This is a mysterious moment because Sarah intends to harm Hagar and Ishmael by exiling them to the barren wilderness on their own. But in spite of Sarah’s evil, God works for Hagar’s good, rescuing her from her oppressive slavery in an exodus-style deliverance. And in the wilderness, Hagar again encounters God, who provides her and Ishmael with life-sustaining water and promises to give Ishmael many descendants (Gen. 21:15-21).

Reflect

What does God’s exodus deliverance of Hagar, Sarah’s Egyptian slave, tell us about how he relates to people who are viewed as outsiders?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

7 And the Lord said, “I have certainly seen the oppression of My people who are in Egypt, and have heard their outcry because of their taskmasters, for I am aware of their sufferings. 8 So I have come down to rescue them from the power of the Egyptians, and to bring them up from that land to a good and spacious land, to a land flowing with milk and honey, to the place of the Canaanite, the Hittite, the Amorite, the Perizzite, the Hivite, and the Jebusite. 9 And now, behold, the cry of the sons of Israel has come to Me; furthermore, I have seen the oppression with which the Egyptians are oppressing them.

10 And now come, and I will send you to Pharaoh, so that you may bring My people, the sons of Israel, out of Egypt.”

16 Go and gather the elders of Israel together and say to them, ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob has appeared to me, saying, “I am indeed concerned about you and what has been done to you in Egypt. 17 So I said, I will bring you up out of the oppression of Egypt to the land of the Canaanite, the Hittite, the Amorite, the Perizzite, the Hivite, and the Jebusite, to a land flowing with milk and honey.”’ 18 Then they will pay attention to what you say; and you with the elders of Israel will come to the king of Egypt, and you will say to him, ‘The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, has met with us. So now, please let us go a three days’ journey into the wilderness, so that we may sacrifice to the Lord our God.’ 19 But I know that the king of Egypt will not permit you to go, except under compulsion. 20 So I will reach out with My hand and strike Egypt with all My miracles which I shall do in the midst of it; and after that he will let you go. 21 I will grant this people favor in the sight of the Egyptians; and it shall be that when you go, you will not go empty-handed. 22 But every woman shall ask her neighbor and the woman who lives in her house for articles of silver and articles of gold, and clothing; and you will put them on your sons and daughters. So you will plunder the Egyptians.”

Consider

Abram once found safety in Egypt during a severe famine (Gen. 12:10). And now, his descendant Joseph is leading efforts to save Egypt from starvation by building massive storehouses of food (Gen. 41). After this, Joseph relocates his own desperately hungry family to Egypt in order to survive (Gen. 46).

Four hundred years pass and a new Pharaoh who never knew Joseph “oppresses” (Hebrew ‘anah) and enslaves the Hebrew people (Exod. 1:8-12), just as Sarai “oppressed” (‘anah) her enslaved Egyptian servant, Hagar (Gen. 16:6).

Just as God “heard” (shama‘) Hagar (16:11), he also “hears” (shama‘) the Israelites “crying out” (za‘aq) in their slavery. “Remembering” (zakar) his promise to make Abraham the father of a great family, or “nation” (Exod. 2:23-24), God responds to the people’s suffering by coming down to lead them on the exodus way. He will deliver them from a world of corruption and bring them into a world of life—his promised land.

God begins the rescue mission by partnering with Moses, an Israelite raised in Pharaoh’s court who has run away to the land of Midian. Calling Moses to return to Egypt, God works through Moses to strike Egypt and its Pharaoh with a series of plagues, just as he plagued the earlier pharaoh's household in order to deliver Abram’s wife, Sarai (Gen. 12:17).

These plagues bring destruction. They’re God’s way of judgement—de-creating Egypt for the way it corrupted, or de-created, the Israelites. The plagues also serve as “signs” (’ot) to demonstrate God’s power, so that both the Egyptians and Israelites will recognize that he is the true God (Exod. 7:1-3, 10:1-2).

But Pharaoh repeatedly hardens his heart (see 7:13, 22) and refuses to listen to God. Only when God strikes Egypt with a tenth and final plague does Pharaoh finally send the Israelites away. As they go, the Egyptians give the Israelites silver, gold, and clothing as compensation for their many years of unpaid labor. Like he did for Hagar before her own exodus, God provides the Israelites with the provisions they will need as they enter the exodus way.

Reflect

What parallels can you draw between the exodus experiences of Abram and Sarai, Hagar, and the Israelites, and how do they help us understand the exodus pattern? What does this pattern reveal about God's character and purposes?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

12 Now the Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, 2 “This month shall be the beginning of months for you; it is to be the first month of the year for you. 3 Speak to all the congregation of Israel, saying, ‘On the tenth of this month they are, each one, to take a lamb for themselves, according to the fathers’ households, a lamb for each household. 4 Now if the household is too small for a lamb, then he and his neighbor nearest to his house are to take one according to the number of persons in them; in proportion to what each one should eat, you are to divide the lamb. 5 Your lamb shall be an unblemished male a year old; you may take it from the sheep or from the goats. 6 You shall keep it until the fourteenth day of the same month, then the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel is to slaughter it at twilight. 7 Moreover, they shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and on the lintel of the houses in which they eat it. 8 They shall eat the flesh that same night, roasted with fire, and they shall eat it with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. 9 Do not eat any of it raw or boiled at all with water, but rather roasted with fire, both its head and its legs along with its entrails. 10 And you shall not leave any of it over until morning, but whatever is left of it until morning, you shall completely burn with fire. 11 Now you shall eat it in this way: with your garment belted around your waist, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it in a hurry— it is the Lord’s Passover. 12 For I will go through the land of Egypt on that night, and fatally strike all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the human firstborn to animals; and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments— I am the Lord. 13 The blood shall be a sign for you on the houses where you live; and when I see the blood I will pass over you, and no plague will come upon you to destroy you when I strike the land of Egypt.

21 Then Moses reached out with his hand over the sea; and the Lord swept the sea back by a strong east wind all night, and turned the sea into dry land, and the waters were divided. 22 So the sons of Israel went through the midst of the sea on the dry land, and the waters were like a wall to them on their right and on their left. 23 Then the Egyptians took up the pursuit, and all Pharaoh’s horses, his chariots, and his horsemen went in after them into the midst of the sea. 24 But at the morning watch, the Lord looked down on the army of the Egyptians through the pillar of fire and cloud, and brought the army of the Egyptians into confusion. 25 He caused their chariot wheels to swerve, and He made them drive with difficulty; so the Egyptians each said, “Let me flee from Israel, for the Lord is fighting for them against the Egyptians.”

26 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Reach out with your hand over the sea so that the waters may come back over the Egyptians, over their chariots and their horsemen.” 27 So Moses reached out with his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to its normal state at daybreak, while the Egyptians were fleeing right into it; then the Lord overthrew the Egyptians in the midst of the sea. 28 The waters returned and covered the chariots and the horsemen, Pharaoh’s entire army that had gone into the sea after them; not even one of them remained. 29 But the sons of Israel walked on dry land through the midst of the sea, and the waters were like a wall to them on their right and on their left.

30 So the Lord saved Israel that day from the hand of the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. 31 When Israel saw the great power which the Lord had used against the Egyptians, the people feared the Lord, and they believed in the Lord and in His servant Moses.

Consider

When Pharaoh repeatedly refuses to let the enslaved Israelites go, God brings one final plague—the death of all the firstborn sons in the land of Egypt. This plague serves as judgment on Egypt for killing the Israelite baby boys (Exod. 1:15-22) and for oppressing Israel, whom biblical authors describe as God’s firstborn son (4:22-23).

Although the flood of death threatens to engulf the Israelites too, God gives them a way to keep their firstborn sons safe. He invites them to smear the blood of a Passover (Hebrew pesakh) lamb on their doorposts to signal their trust in God. When God sees this sign, he will pasakh—that is, pass over or protect—their homes from the destroyer, thus sparing their children. God calls Israel to celebrate the Passover every year to reenact his deliverance during their great exodus.

This death strike compels Pharaoh to release the Israelites, but he soon changes his mind. As they flee, he pursues them to the edge of the sea. With the Egyptian army on one side and the deadly, chaotic waters on the other, Israel’s destruction seems unavoidable.

But God rescues his people again. He divides the waters and creates a dry path through the middle of the sea. God leads the Israelites out of certain death and toward the promise of new life. The mighty Egyptian army gives chase, but God lets a flood of water engulf them. Then he leads Israel on the exodus way, through the wilderness—a place of scarcity and provision, blessing and testing. In the wilderness, they learn what it looks like to “serve” (or “worship,” ‘avad, Exod. 3:12) a life-giving Lord” instead of serving the death-dealing Pharaoh (the ‘avad root appears five times in Exod. 1:13-14). And ultimately, God brings them into the land he promised to give them (Gen. 15:12-21).

Reflect

What are some threats the Israelites face in this story, and how does God rescue them from those threats?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

10 Then on that day

The nations will resort to the root of Jesse,

Who will stand as a signal flag for the peoples;

And His resting place will be glorious.

11 Then it will happen on that day that the Lord

Will again recover with His hand the second time

The remnant of His people who will remain,

From Assyria, Egypt, Pathros, Cush, Elam, Shinar, Hamath,

And from the islands of the sea.

12 And He will lift up a flag for the nations

And assemble the banished ones of Israel,

And will gather the dispersed of Judah

From the four corners of the earth.

13 Then the jealousy of Ephraim will depart,

And those who harass Judah will be eliminated;

Ephraim will not be jealous of Judah,

And Judah will not harass Ephraim.

14 They will swoop down on the slopes of the Philistines on the west;

Together they will plunder the people of the east;

They will possess Edom and Moab,

And the sons of Ammon will be subject to them.

15 And the Lord will utterly destroy

The tongue of the Sea of Egypt;

And He will wave His hand over the Euphrates River

With His scorching wind;

And He will strike it into seven streams

And make people walk over in dry sandals.

16 And there will be a highway from Assyria

For the remnant of His people who will be left,

Just as there was for Israel

On the day that they came up out of the land of Egypt.

40 “Comfort, comfort My people,” says your God.

2 “Speak kindly to Jerusalem;

And call out to her, that her warfare has ended,

That her guilt has been removed,

That she has received of the Lord’s hand

Double for all her sins.”

3 The voice of one calling out,

“Clear the way for the Lord in the wilderness;

Make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

4 “Let every valley be lifted up,

And every mountain and hill be made low;

And let the uneven ground become a plain,

And the rugged terrain a broad valley;

5 Then the glory of the Lord will be revealed,

And all flesh will see it together;

For the mouth of the Lord has spoken.”

6 A voice says, “Call out.”

Then he answered, “What shall I call out?”

All flesh is grass, and all its loveliness is like the flower of the field.

7 The grass withers, the flower fades,

When the breath of the Lord blows upon it;

The people are indeed grass!

8 The grass withers, the flower fades,

But the word of our God stands forever.

9 Go up on a high mountain,

Zion, messenger of good news,

Raise your voice forcefully,

Jerusalem, messenger of good news;

Raise it up, do not fear.

Say to the cities of Judah,

“Here is your God!”

10 Behold, the Lord God will come with might,

With His arm ruling for Him.

Behold, His compensation is with Him,

And His reward before Him.

11 Like a shepherd He will tend His flock,

In His arm He will gather the lambs

And carry them in the fold of His robe;

He will gently lead the nursing ewes.

Consider

Centuries after the Israelites enter and settle the promised land, they experience corruption, war, and the utter destruction of all they’ve established. Babylonian armies destroy Jerusalem and exile the people, which God describes as a consequence for violating their covenant agreement with God.

But Isaiah 40:3 describes a voice calling the exiles to “prepare the way of Yahweh.” God is coming to lead the people on a new exodus way—the way out of exile, through the wilderness, and back to their good land. As it happened during the big exodus from Egypt, God delivers his people from exile with his powerful arm (40:10; see Exod. 6:6). But his arms will also tenderly carry and protect them, as a shepherd carries a vulnerable lamb or as a mother bird protects her young by pulling them under her wing.

Earlier, God worked through Moses; now he promises to raise up a “root of Jesse,” that is, a king from the line of David (Isa. 11:10). This human agent will draw the attention of the nations as God gathers his exiled people and reunites the long-divided kingdoms of Judah and Israel (here called Ephraim).

When the people escape from their exilic oppressor, they walk away with heaps of valuable plunder (Isaiah 11:14), just like the Israelites who plundered Egypt during their own escape (Exod. 12:36). And just as God divided the waters of the Red Sea with a wind (Exod. 14:21–22), here he sends a wind to make a pathway through the Euphrates River (Isa. 11:15). So once again, on their exodus way, the people will walk through the water on dry ground as they begin their journey home.

Reflect

How does Israel’s exodus from Egypt inform Isaiah's vision of a new kind of exodus? What role does the David figure play in this new exodus?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

1 The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God,

2 just as it is written in Isaiah the prophet:

“Behold, I am sending My messenger ebefore You,

Who will prepare Your way;

3 The voice of one calling yout in the wilderness,

‘Prepare the way of the Lord,

Make His paths straight !’”

4 John the Baptist appeared in the wilderness, preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. 5 And all the country of Judea was going out to him, and all the people of Jerusalem; and they were being baptized by him in the Jordan River, confessing their sins. 6 John was clothed with camel’s hair and wore a leather belt around his waist, and his diet was locusts and wild honey. 7 And he was preaching, saying, “After me One is coming who is mightier than I, and I am not fit to bend down and untie the straps of His sandals. 8 I baptized you with water; but He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit.”

Consider

The Gospel of Mark opens by quoting Isaiah 40:3 to show how God’s ancient promise is starting to see real fulfillment—a new kind of exodus is beginning. John the Baptizer becomes the voice in Isaiah that cries out in the wilderness and prepares people for the exodus way of life. First, they are led through the waters of baptism (as Moses led the Israelites through the waters of the Red Sea, Exod. 14:21-29). And second, they are called to repent, or to change direction. This is all because God himself will arrive and lead a massive, all-humanity kind of exodus.

Isaiah 40’s vision of the exodus way out of Babylonian exile was fulfilled in part when some of the Jews returned to their land (see Ezra 1-2). But even though God freed the Jews from exile, they needed deliverance from a deeper kind of bondage. The New Testament reveals that the true oppressor is not a person, like a pharaoh, or an empire, like Babylon or even Rome. Instead, the powers of sin and death enslave humans (see John 8:34; Eph. 6:12) so that they harm each other and all of creation. So John’s baptism is a cleansing ceremony that marks their entry into the exodus way. And this will be the ultimate exodus—greater than all the previous exodus moments in the story. In this new exodus, Jesus will rescue humanity from every destructive desire that leads to death. And humanity will begin to experience the true and good life that they will enjoy forever in God’s kingdom.

Reflect

What is John the Baptizer’s role in the ultimate exodus? How does the ultimate exodus go beyond what Isaiah 40 describes? And is the exodus way simply about moving from a bad place to a good one, or is there more to the story?

Read

13 Now when they had gone, behold, an angel of the Lord *appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up! Take the Child and His mother and flee to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you; for Herod is going to search for the Child to kill Him.”

14 So Joseph got up and took the Child and His mother while it was still night, and left for Egypt. 15 He stayed there until the death of Herod; this happened so that what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet would be fulfilled: “Out of Egypt I called My Son.”

16 Then when Herod saw that he had been tricked by the magi, he became very enraged, and sent men and killed all the boys who were in Bethlehem and all its vicinity who were two years old or under, according to the time which he had determined from the magi. 17 Then what had been spoken through Jeremiah the prophet was fulfilled:

18 “A voice was heard in Ramah,

Weeping and great mourning,

Rachel weeping for her children;

And she refused to be comforted,

Because they were no more.”

19 But when Herod died, behold, an angel of the Lord *appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, and said, 20 “Get up, take the Child and His mother, and go to the land of Israel; for those who sought the Child’s life are dead.” 21 So Joseph got up, took the Child and His mother, and came into the land of Israel. 22 But when he heard that Archelaus was reigning over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there. Then after being warned by God in a dream, he left for the regions of Galilee, 23 and came and settled in a city called Nazareth. This happened so that what was spoken through the prophets would be fulfilled: “He will be called a Nazarene.”

9 In those days Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. 10 And immediately coming up out of the water, He saw the heavens opening, and the Spirit, like a dove, descending upon Him; 11 and a voice came from the heavens: “You are My beloved Son; in You I am well pleased.”

12 And immediately the Spirit *brought Him out into the wilderness. 13 And He was in the wilderness for forty days, being tempted by Satan; and He was with the wild animals, and the angels were serving Him.

14 Now after John was taken into custody, Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of God, 15 and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent and believe in the gospel.”

Consider

The gospels portray Jesus as a new Israel with his own exodus experience. After Mary gives birth to Jesus, the Judean King Herod hears about the arrival of a new king. Immediately fearful and jealous, Herod commands the murder of all the baby boys in the region (Matt. 2:16-18), just as Pharaoh killed the Israelite baby boys (Exod. 1:15-22).

Fleeing from Herod, Jesus’ family seeks refuge in Egypt (just as Abraham and Joseph did) until an angel tells them it’s safe to return to Israel. Matthew 2:15 describes Jesus’ time in Egypt as the fulfillment of Hosea 11:1: “Out of Egypt I called my son” (NASB). So Jesus reenacts Israel’s story through his own exodus out of Egypt.

Many years later, Jesus is baptized, passing through the waters of the Jordan River, just as the Israelites passed through the waters of the Red Sea on their own exodus way (Exod. 14:21-29). And like Israel (4:22), he is called God’s Son.

Then the Spirit leads Jesus into the wilderness to be tested for 40 days, similar to God testing the Israelites in the wilderness for 40 years (Exod. 16:1-7; Deut. 8:2). Although the Israelites revealed their unfaithfulness by testing God with their grumbling (Exod. 17:1-7), Jesus demonstrates unwavering faithfulness (see Matt. 4:1-11).

So as the true Israel, Jesus announces that the kingdom of the skies, the new promised land, has come near. And he begins to fulfill Israel’s mission—to bring blessing to every family or “nation” on Earth (see Gen. 12:3)—by reflecting God’s love and offering healing and wholeness to the people around him.

Reflect

What do the similarities between Israel’s exodus from Egypt and Jesus’ exodus teach us about Jesus’ mission on earth?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

6 Your boasting is not good. Do you not know that a little leaven leavens the whole lump of dough? 7 Clean out the old leaven so that you may be a new lump, just as you are in fact unleavened. For Christ our Passover also has been sacrificed. 8 Therefore let’s celebrate the feast, not with old leaven, nor with the leaven of malice and wickedness, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth.

3 So we too, when we were children, were held in bondage under the elementary principles of the world. 4 But when the fullness of the time came, God sent His Son, born of a woman, born under the Law, 5 so that He might redeem those who were under the Law, that we might receive the adoption as sons and daughters. 6 Because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of His Son into our hearts, crying out, “Abba! Father!” 7 Therefore you are no longer a slave, but a son; and if a son, then an heir through God.

14 For all who are being led by the Spirit of God, these are sons and daughters of God. 15 For you have not received a spirit of slavery leading to fear again, but you have received a spirit of adoption as sons and daughters by which we cry out, “Abba! Father!” 16 The Spirit Himself testifies with our spirit that we are children of God, 17 and if children, heirs also, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, if indeed we suffer with Him so that we may also be glorified with Him.

Consider

Not only is Jesus a new Israel, he’s also a new Moses, who leads humanity into the ultimate exodus. This exodus is not an escape from a single oppressor (like Sarai) or from a particular empire (like Egypt or Rome). It is an exodus way out from enslavement by evil principalities and powers that motivate every act of harm and human oppression (see John 8:34; Eph. 6:12).

So just as God redeemed his firstborn “son” Israel from slavery in Egypt (Exod. 4:22), now he redeems people from slavery to these powers through his Son, Jesus. As a Passover lamb, Jesus’ blood protects people from the death-dealing effects of their harmful desires. God invites us to follow Jesus into baptism, passing through the waters of death into a new way of life. Then we are adopted as God’s children, receiving the promise of an inheritance in the new heavens and new earth (see Rev 21:1-4).

But while God leads us on the exodus way out of slavery, we’re not entirely free yet. Like Israel in the wilderness, we still await our promised inheritance. As we journey through the wilderness, God forms us into a new kind of people who love all other human beings—neighbors and enemies alike. And he invites us to live in the way of peace that characterizes his eternal, good Kingdom.

Joining with Jesus as part of the true Israel, we embrace Israel’s calling to become a genuine, generous blessing to all the families, or “nations,” on Earth (see Gen. 12:3). The exodus way guides us along a path of transformation that, in the end, moves us to continuously reflect God’s lovingkindness and peacefulness to the world around us.

Reflect

How might the hope of our future inheritance in the new heavens and new earth affect how we live now as we journey through the wilderness?

More Relevant Scripture References

Read

18 For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory that is to be revealed to us. 19 For the eagerly awaiting creation waits for the revealing of the sons and daughters of God. 20 For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope 21 that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children of God. 22 For we know that the whole creation groans and suffers the pains of childbirth together until now. 23 And not only that, but also we ourselves, having the first fruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting eagerly for our adoption as sons and daughters, the redemption of our body. 24 For in hope we have been saved, but hope that is seen is not hope; for who hopes for what he already sees? 25 But if we hope for what we do not see, through perseverance we wait eagerly for it.

26 Now in the same way the Spirit also helps our weakness; for we do not know what to pray for as we should, but the Spirit Himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words; 27 and He who searches the hearts knows what the mind of the Spirit is, because He intercedes for the saints according to the will of God.

13 For He rescued us from the domain of darkness, and transferred us to the kingdom of His beloved Son, 14 in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.

15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation: 16 for by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones, or dominions, or rulers, or authorities— all things have been created through Him and for Him. 17 He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together. 18 He is also the head of the body, the church; and He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that He Himself will come to have first place in everything. 19 For it was the Father’s good pleasure for all the fullness to dwell in Him, 20 and through Him to reconcile all things to Himself, whether things on earth or things in heaven, having made peace through the blood of His cross.

Consider

By defeating the powers of sin and death, Jesus offers an exodus deliverance not only for all humanity, but for all of creation. The biblical story begins with God creating humans as caretakers who “serve” and “keep” his created world. But they choose to do what is right in their own eyes instead of submitting to God’s wisdom. So the whole world suffers, languishing in bondage to the forces of destruction.

Like the Israelites in Egypt (Exod. 3:7-9), creation groans, longing for freedom. Its voice joins our cries for God to restore all things. And just as God heard the Israelites crying out in their bondage, so God hears these cries. In fact, the Spirit’s voice cries out along with humans and creation, “with groanings too deep for words” (Rom. 8:26) that are taken into the very heart of God.

Through Jesus’ death and resurrection, God begins to redeem the whole cosmos. He is working to unite Heaven and Earth together as one and bring about a new Eden. And he invites us to participate in his restoring work by living according to his wisdom and fulfilling our human calling to serve as caretakers of his good creation.

Reflect

How can we participate in God’s work of redeeming all of creation?

More Relevant Scripture References

Frequently Asked Questions

The exodus way is a complex topic, and you probably still have questions. Here are some of the ones we hear most often.

The term “exodus” is from the Greek exodos, meaning “departure.” In the Bible, it refers to Israel's escape from Egyptian slavery, as noted in the early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible called the Septuagint (Exod. 19:1). It symbolizes God's deliverance in three stages: the way out of oppression, the way through a place of testing and transformation, and the way into promise.

Israel’s exodus from Egypt provides a model for this pattern. So as we study how God delivers the Israelites out of slavery, leads them through the wilderness, and brings them into the promised land, we begin to recognize how the exodus pattern appears in other places as well.

When we look more closely, we find exodus in some surprising places. Not only does Abraham have an exodus from Egypt (Gen 12:10-20), but the Egyptian Hagar has an exodus from her enslavement to Abraham and Sarah (Gen. 21:9-21)! And in Amos 9:7, God compares Israel’s exodus from Egypt to how he brought “the Philistines from Caphtor and the Arameans from Kir,” suggesting that even some of Israel’s enemies have an exodus experience. These passages and others like them remind us that God desires to bring deliverance and life to all people.

The story of Israel’s exodus from Egypt reveals many things about God. For example, it shows us that:

- God hears the outcry of the oppressed and responds with compassion (Exod. 3:7-8).

- He is faithful to his promises—here, to his agreement with Abraham to make his family immense (Exod. 2:24-25; see Gen. 15:12-21).

- He is a God of justice, who makes proud oppressors eat the fruit of their destructive behavior (Exod. 4:22-23).

- He is also patient. He confronts people to give them the opportunity to turn away from their death-dealing actions and follow his ways (Exod. 5:1-9).

- Since he created the heavens and the earth, all creation responds to him (see Exod. 14:21-29; also Ps. 74:12-17).

- He is more powerful than the mightiest kings of the Earth and the gods of other nations (Exod. 15:4; Exod. 15:11).

- He doesn’t simply move people from a bad place to a good place, but also works to transform them into new kinds of people who follow his ways (e.g., Exod. 19:3-6; Ezek. 36:26; Heb. 8:10).

Israel’s exodus from slavery in Egypt is the paradigmatic act of salvation in the Old Testament (or Hebrew Bible), paralleling Jesus’ death and resurrection in the New Testament. Within the Hebrew Bible, the exodus establishes a model of God saving his people from human enemies or from death (Exod. 14:30; Exod. 15:2; Ps. 18:1-2; Ps. 30:3).

But the New Testament reveals that our true enemies are actually the cosmic powers of sin and death, not human beings (Eph. 6:12). Sin is a death-dealing master, which enslaves all people (John 8:34). It motivates and animates the worst acts of human brutality and leads us all to behave in ways we were not designed for—ways of corruption and harm (Rom. 7:14-20). So God offers us an exodus way of deliverance from that slavery.

The Israelites’ exodus from Egypt (and the other exodus stories in the Bible) suggest that salvation is more than escaping a bad situation and moving into a new situation. God does promise to move humanity out of a corrupted world and into a renewed world. But exodus also involves the transformation of humanity into a new kind of people. In the exodus way, salvation is about escaping oppression and being set free. And it’s about becoming a new kind of person, characterized by undying love for God, for creation, and for every human being in the world—friend and foe alike.

Salvation is about God’s sovereign, unstoppable power and love leading us to trust in him and participate in his plan to restore all things. The one human who most fully embraces the exodus way is Jesus of Nazareth, whom God sent to lead humanity out of captivity.

Uniting with Jesus in his death and resurrection—symbolized by passing through the waters of baptism—involves ongoing decisions to trust God’s will over-against one’s own. As people surrender to God’s ways, they experience an increasing freedom or “salvation” from the corruption of sin and death (Rom. 6:1-7).

Some scholars date Israel’s exodus from Egypt to the 15th century B.C.E. (around 1446 B.C.E.), while others date it to the 13th century B.C.E. (around 1275-1250 B.C.E.). Those who support the earlier date point to the chronology within the Bible. In 1 Kings 6:1 the fourth year of Solomon’s reign, which is dated around 966 B.C.E., is identified as 480 years after the exodus. And Judges 11:26 says that Israel had lived in Canaan for 300 years before Jephthah became a judge, perhaps around 1100 B.C.E. Since the Israelites wandered in the wilderness for 40 years after the exodus before entering Canaan, that would make the exodus around 1440 B.C.E.

Those who follow the later date point to archaeological evidence, which they see as suggesting that Israel entered Canaan in the late 13th century. They also note that biblical authors sometimes use numbers symbolically. So the 480 years in 1 Kings 6:1 could refer to 12 generations, even though the actual length of a generation would be less than 40 years. And the 300 years in Judges 11:26 could be an exaggerated or estimated number.

But identifying when the exodus happened is less important than understanding what the exodus means. The exodus is the foundational event that forms Israel’s identity as God’s people and establishes the paradigm for the biblical concept of salvation.

Because God reveals his loving and compassionate character by rescuing the Israelites from “slavery” (Hebrew ‘avodah) in Egypt (Exod. 2:23), they “serve” (or “worship,” the related verb ‘avad) him by honoring him as God and demonstrating his love and compassion toward others (see Deut. 10:17-22). The exodus reveals that Israel’s God hates slavery, oppression, and everything that harms human beings. And he acts to rescue, heal, and bless people with freedom in a good world full of unbreakable love and always abundant resources.

A 15th-century date for the exodus suggests Thutmose III or Amenhotep II, while a 13th-century date points to Ramesses II, connecting with the mention of the city of Raamses in Exodus 1:11.

Interestingly, the biblical book of Exodus never honors the Pharaoh by giving him a name. He’s just “Pharaoh.” Instead of memorializing his name, Exodus records—and therefore honors—the names of the seemingly powerless Hebrew midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, who defy the mighty Pharaoh by refusing to obey his command to kill the Hebrew baby boys (Exod. 1:15-21). Their strong-willed refusal to participate in Pharaoh’s program of death is portrayed as more powerful than his royal might.

And the nameless Pharaoh of the exodus also becomes a symbol for proud oppressors who show up elsewhere in the biblical story. In fact, the repeated use of the exodus pattern warns us that anyone can become like this harmful pharaoh. In Genesis 16:1-16 and 21:9-21, Abraham and Sarah play the role of Pharaoh when they oppress Sarah’s Egyptian slave, Hagar. And later, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar functions as Pharaoh when he sends the Israelites into exile (2 Kgs. 25).

Since God knows how easy it is for people to abuse their power, he calls the Israelites to remember their experience of slavery in Egypt so that they will be compassionate toward the vulnerable among them and not oppress others as they were once oppressed (see Deut. 15:12-15; Deut. 24:17-22).

The exodus narrative describes 10 plagues that God brings on Egypt so that Pharaoh will let the Israelites go (see Exod. 9:13-14).

- Water turned to blood (Exod. 7:14-25)

- Frogs (Exod. 8:1-15)

- Gnats (Exod. 8:16-19)

- Flies (Exod. 8:20-32)

- Disease on livestock (Exod. 9:1-7)

- Boils (Exod. 9:8-17)

- Hail (Exod. 9:18-35)

- Locusts (Exod. 10:1-20)

- Darkness (Exod. 10:21-29)

- Death of the firstborn (Exod. 11:1-12:32)

Not only do these plagues bring judgment against the Egyptians for oppressing the Israelites, but they’re also intended to reveal to both Egypt and Israel that Yahweh is the true God (Exod. 7:3-5; 10:1-2). So they’re often called “signs” (Hebrew ’ot; see Exod. 8:23) or “wonders” (mophet; see Exod. 4:21).

Along with the 10 listed above, Exodus 4:1-8 describes two additional signs to demonstrate God’s power: Moses’ staff turns into a snake, which later eats up the snake-staffs of the Egyptian magicians (Exod. 7:8-13), and Moses’ hand becomes temporarily diseased.

Before God sends any plagues on Egypt, he confronts Pharaoh to give him a chance to turn away from his oppressive enslavement of the Israelites (Exod. 5:1-9). When Pharaoh refuses, God brings plagues that increase in severity—from annoying disruptions to lost crops and painful sores and finally to the death of the Egyptians’ firstborn sons.

God gives Pharaoh multiple low-stakes opportunities to recognize his power and relent before any destruction falls on Egypt. And Exodus 9:20-21 suggests that the Egyptians had a choice whether they would seek protection from the plagues by listening to God’s voice or follow Pharaoh in resisting God.

In Exodus 4:21, God tells Moses that he “will harden” Pharaoh’s heart, yet Pharaoh first hardens his own heart repeatedly (Exod. 7:13, Exod. 7:22; Exod. 8:15, Exod. 8:19, Exod. 8:32; Exod. 9:7). God gives Pharaoh multiple chances to relent and stop oppressing the Israelites, intervening only after Pharaoh persistently resists (Exod. 9:12).

So when God finally acts to harden Pharaoh’s heart, it does not appear that he is forcing or coercing the Pharaoh to act contrary to his own desire. Instead, the narrative suggests that God is further strengthening Pharaoh’s resolve to follow the path he has already chosen. By bringing Pharaoh to the end of that path—the point of judgment—God delivers the Israelites from his hand.