Were Adam and Eve Priests in Eden?

Humanity as Priests in God’s Cosmic Temple

The Bible begins with a bold claim: all of creation is God’s temple.

The first creation narrative in Genesis 1:1-2:3 depicts God as a cosmic-temple builder. God creates an ordered world out of a dark wasteland in seven days. And on the seventh day, God’s presence fills creation as he takes up his rest and rule in his temple.

In Genesis 2:4b-3:24, we find a complementary creation account focusing on the garden of Eden. This account depicts God ordering the world out of a chaotic wilderness and placing humans in a garden-temple.

But if the garden is a temple, does that make humanity the priests?

Creation as God’s Temple

Let’s first take a look at how God’s world is depicted as his temple. Although creation is not explicitly called a temple in the text, the literary design of the first creation account in the Hebrew Bible frames creation as God’s temple.

Notice that the creation story is told in a period of seven days. This is significant! In the ancient Israelites’ world, temples were always dedicated with a seven-day ceremony. This was true not only of the Israelites’ temple built for their God (Leviticus 8:33-35; 1 Kings 8:2; 1 Kings 8:65; Ezekiel 43:25-27), but also of neighboring nations’ temples which they raised for their deities. This ritual was so deeply ingrained in ancient culture that the Israelites would have immediately understood a seven-day creation story to mean that creation itself was a temple for their God.

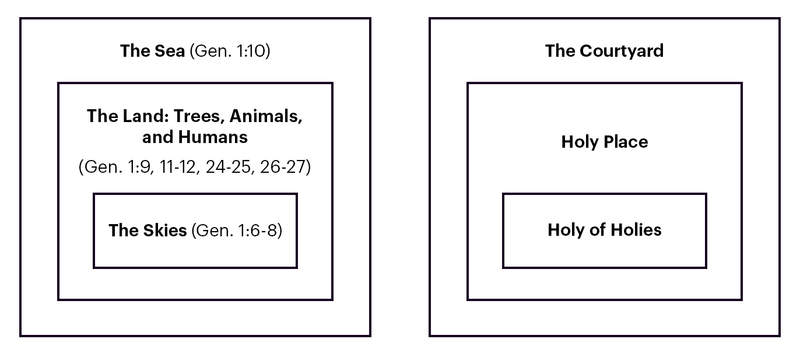

We can see the Israelites’ understanding of the design of creation in the three-part design of the Israelite tabernacle and temple (holy of holies, holy place, and courtyard).

This parallel states a significant truth about creation itself: the cosmos is a macro temple, and the temple is a miniature cosmos. Just as ancient worshipers placed a statue of their god in the heart of a temple, humanity is placed in God’s cosmic temple as his image (tselem or “idol”)—an embodied physical image of the divine creator and king (Genesis 1:26-27).

Heaven and Earth are not meant to be separate realms. Rather, they are meant to completely overlap. God appointed creation as the place where humans would be united with the beauty and presence of God for all eternity.

The Garden of Eden as a Temple

All of creation is God’s temple. And in the middle of this cosmic temple, God creates another temple—a garden.

The concept of Eden described as a cosmic mountain-temple would not be unfamiliar to ancient readers. The great pyramids of Egypt, ziggurats of Babylon, and ancient palace gardens all pay homage to these concepts. These buildings were designed to evoke transcendence and awe. They were sacred spaces where humans and their gods could meet. Only priests were allowed inside most temples because they functioned as mediators between the gods and the people of the city. In the ancient Near East, the temple was the center and mainstay of creation. And in the Genesis account, the garden of Eden is depicted as the center and mainstay of God’s creation.

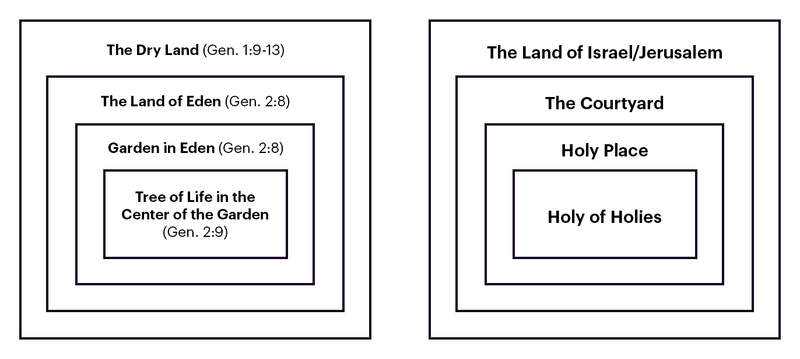

The design plan of Eden is a prototype of the tabernacle and the temple. This narrative is meant to preview the priesthood and the holy of holies in the Israelite tabernacle and temple. The map of Genesis 2:4-18 imitates that of the holy space.

Later on in the Hebrew Bible, God instructed Israelite leaders to incorporate garden imagery into the tabernacle and the temple. The tree of life (Genesis 2:9) is symbolized by the lampstand in the tabernacle and temple (Exodus 25:31-40). The danger of the “middle” of the garden is like the danger of “holy ground” for Jacob at Bethel (Genesis 35:2) and for Moses and the Israelites in Sinai (Exodus 3:5; Exodus 19:1-12).

The tree of “knowing” good and bad in the middle of the garden (Genesis 2:8) that is not to be approached (Genesis 2:17) is like the tablets of the Torah placed in the ark of the covenant in the holy of holies (Deuteronomy 31:26), which is Israel’s “wisdom” (Deuteronomy 4:4-6) and “life” (Deuteronomy 32:46-47).

And just as the entrance to Israel’s first temple faced east and was situated on a mountain (Exodus 15:17), the future temple described in Ezekiel was also to face east (Ezekiel 40:6) and be built on a mountain (Ezekiel 40:6; Ezekiel 40:2; Ezekiel 43:12). Similarly, Eden’s entrance faced east (Genesis 3:24) and was on a mountain (Ezekiel 28:14; Ezekiel 28:16).

These designs are intentional. Every image points back to the garden-temple of Eden.

Adam and Eve as Priests in the Garden of Eden

If the biblical authors wanted us to see the garden as a temple, are we to see Adam and Eve as priests?

Actually, it seems that this is exactly what the authors had in mind. In the garden-temple, humanity served as God’s royal representatives, or priests.

In the Hebrew Bible, the temple was where priests uniquely experienced God’s presence. In the garden, humanity fully experienced God’s presence—walking and talking with him. The Hebrew verbal form (hithpael) used for God’s “walking back and forth” in the garden (Genesis 3:8) also describes God’s presence in the tabernacle (Leviticus 26:12; Deuteronomy 23:14; 2 Samuel 7:6-7; Ezekiel 28:14). Additionally, in Genesis 2:15, humanity’s work is described in priestly vocabulary:

“...and Yahweh Elohim took the human and placed him into the garden of Eden to work it and keep it.”

These two verbs in Genesis 2:15 are packed with significance, as they portray the ideal vocation of humanity.

The Hebrew word ‘abad (עבד) can be translated as “to work,” “to serve,” or “to worship.” It is a common verb and is often used for cultivating the soil (Genesis 2:5; Genesis 3:23; Genesis 4:2; Genesis 2:12). However, the word is also commonly used in a religious sense of serving God (Deuteronomy 4:19) and in priestly texts, especially regarding the tabernacle duties of the Levites (Numbers 3:7-8; Numbers 4:23-24; Numbers 4:26).

The second Hebrew word, translated as “to keep,” is shamar (שמר), which is commonly used for a priestly service of worship, as well as in legal texts of observing religious commands and duties (Leviticus 18:5). The word is also used for the Levitical responsibility of guarding the tabernacle from intruders (Numbers 1:53; Numbers 3:7-8).

These two verbs ‘abad (עבד) and shamar (שמר) are used together as a phrase to refer either to Israelites serving and guarding/obeying God’s word, or, more frequently, of the priests and the Levites who serve God in the temple and who guard the temple (Numbers 3:7-8; Numbers 8:25-26; Numbers 18:5-6; 1 Chronicles 23:32; Ezekiel 44:14).

As God’s priestly representatives, Adam and Eve were to be mediators between God and others—relating with God on behalf of other people and reflecting his character to others through love, compassion, generosity, and justice.

As priests, Adam and Eve were tasked to care for this sacred space. They were to “work and serve” by participating with God in the ongoing task of upholding and sustaining the order God had established in the cosmos. And God tasked humanity with using their own creative power and imagination to spread the order and beauty of the garden-temple into the rest of creation.

Priestly Failure and Future Hope

Knowing their original priestly function makes Adam and Eve’s rebellion in Genesis 3 all the more tragic. They take and eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and bad and they spread mistrust, violence, and death to the whole world instead of the blessing of Eden. God exiles humanity from the ordered garden-temple into the chaos of the wilderness.

But this exile is not without hope. Before they leave the garden-temple, Adam and Eve receive a promise of a future “seed” (Genesis 3:15) who would come to defeat evil and restore creation. And he will be the one to fulfill the priestly role.

The ideal design of creation, the garden-temple, and humanity’s role as priests, teaches us about our ideal role as humanity. Humans were created to be priestly representatives as divine image-bearers. We were created to relate with God and to reflect his character to others. We were created to “work and serve,” to uphold and sustain, and to unleash our creative power and imagination to spread the order and beauty of the garden-temple into the rest of creation.

In what ways are we fulfilling this ideal? How are we living out our intended role as priests? How are we reflecting God’s character to those around us? How are we pursuing justice, showing compassion, and spreading order, beauty, and the garden into the rest of creation?

The creation account invites us to ponder and reflect on our ideal role as priests, our failure to live up to that ideal, and the hope we have because of Jesus, the future “seed” who created a new humanity and new kingdom of priests, and who will one day reunite Heaven and Earth.

And in this new creation—this new garden—humanity will “work and serve” and rule once again as God’s image-bearers and priests in his cosmic temple.

This post is the first in "The Royal Priest" blog series, read the next article in the series "Abraham, Melchizedek, and Jesus". This article is related to "The Royal Priest" video series.

This article was written by Shara Drimalla with scholarly editorial review by Dr. Carissa Quinn. Additional scholar research and resources provided by Dr. Tim Mackie. Copy-edited by Kenzie Halbert-Howen.