The Book of Galatians

About

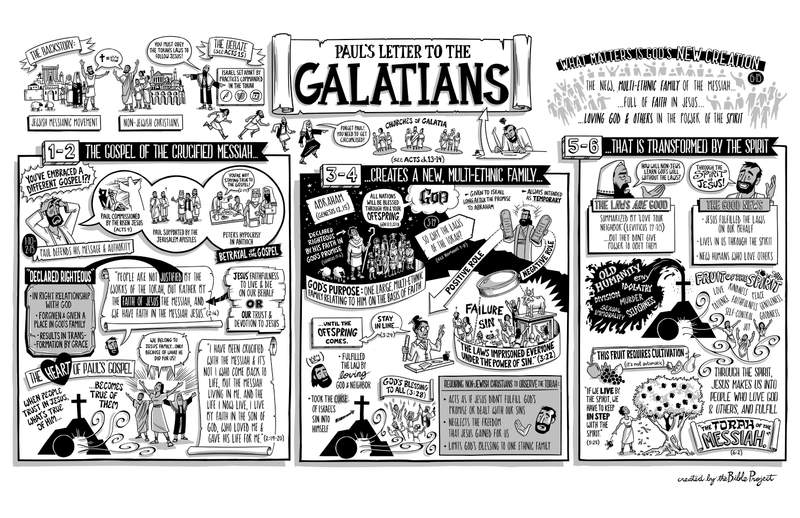

Galatians was addressed to a number of churches in the region of Galatia, where Paul had traveled on one of his missionary journeys (Acts 13-14). He wrote this important letter from a place of deep passion as well as frustration.

Background of the Book of Galatians

Christianity had begun as a Jewish messianic movement in Jerusalem, but its message was for all humanity, so it quickly spread beyond Israel. By the time Paul became a missionary, there were as many non-Jews as there were Jewish people in the Jesus movement. This conflict of cultures sparked major debate that came to a head in the events recounted in Acts 15. Historically, the covenant people of God were from one nation, Israel, and they were set apart by practices commanded in the Torah, like circumcision of males, eating kosher, and observing the Sabbath. There were many Jewish Christians who believed that for non-Jews to truly become a part of God’s covenant family, they needed to obey the laws of the Torah as well. Some of these Jewish Christians had come to the Galatian churches and began undermining Paul, demanding the circumcision of all male Christians.

When Paul found out, he was both heartbroken and angry. He wrote this letter in response, challenging the Galatians with a summary of the Gospel message about the crucified Messiah. He argues that this Gospel is what creates the new, multiethnic family of God, truly transforming people through the presence and power of Jesus’ Spirit.

Galatians 1-2: A New Covenant Family Through Jesus

Paul expresses his bewilderment that the Galatians have embraced “a different gospel,” one promoted by the Christians who were badmouthing Paul and demanding circumcision. Paul defends the authenticity of his message and authority as an apostle, reminding them that he was commissioned by the risen Jesus himself to go into the non-Jewish world (Acts 9). Paul says that it was only much later that he went to Jerusalem to consult the other apostles, like Peter and James. When he told them that he was not requiring non-Jewish Christians to be circumcised or eat kosher, they were in full support.

However, the tension ran deeper when Peter came to visit Antioch and saw all these non-Jewish Christians. Peter was perfectly fine with eating and mingling with them, but when some of the Jerusalem opposition group showed up in town, Peter caved under the pressure. He stopped eating with the uncircumcised Christians and even started to avoid them. Paul confronted and accused Peter of hypocrisy as well as “not staying true to the Gospel” (Gal. 2:14).

To Paul, demanding that these new Christians become circumcised and Torah observant is wrongheaded for lots of reasons, first and foremost because it’s a betrayal of the Gospel. In Paul’s words, “People are not justified by the works of the Torah, but rather by the faith of Jesus the Messiah, and we have faith in the Messiah Jesus” (Gal. 2:16). To be justified or declared righteous are rich Old Testament terms for Paul. When God declares that someone is in a right relationship with him, it means that they’re forgiven, given a place in God’s family, and in the process of being transformed by God’s grace. It’s Paul’s conviction that you can’t be justified by observing the commands of the Torah but only through “the faith of Jesus.” This is a dense phrase that could refer to Jesus’ own faithfulness in living and dying on our behalf or our own trust and devotion to Jesus. Either way, the point is clear: People are justified only through trusting what God did for them through Jesus—not by what they do for themselves.

At the heart of the Gospel that Paul teaches is the claim that when people trust in the Messiah Jesus, what’s true of him becomes true of them. His life, death, and resurrection all become theirs. Or in Paul’s words, “I have been crucified with the Messiah, and it’s not I who came back to life, but it’s the Messiah living in me. The life I now live, I live by faith in the Son of God who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2:19-20).

The reason people can say that they are right with God and belong to Jesus’ covenant family is not because they obeyed the laws of the Torah but because of what Jesus did for them—something they could never do for themselves. This understanding of what Jesus accomplished has profound implications for who can be included in God’s covenant family as well as what it means to live as a member of that family.

Galatians 3-4: The Role of the Law Within God’s Multiethnic Family

Paul turns back to the stories about Abraham, recalling how he was justified or declared righteous before God for simply having faith and trusting in God’s promise that one day all nations would find God’s blessing through him and his offspring (Gen. 15:6). In other words, God’s purpose was always to have one large, multiethnic family of people who relate to him on the basis of faith, not the laws of the Torah.

This line of thought raises an important question. If God’s plan was always to have a multiethnic family, why did he give the laws of the Torah to Israel in the first place (Gal. 3:19)? Paul offers a brief, dense explanation that he fills out in chapters 7-8 of his letter to the Romans. He observes that the laws of the Torah were given to Israel at Mount Sinai long after God’s promise to Abraham. If you read the Torah carefully, you’ll see that God had always intended the laws to be a temporary measure.

Paul continues by saying that the laws had both a negative and positive role. Negatively, the laws acted like a magnifying glass on Israel’s sin, exposing how Israel shared in the sinful human condition and constantly rebelled against God. So the law, which is essentially good, ended up pronouncing Israel guilty along with the rest of humanity. As Paul says, “the laws imprisoned everyone under the power of sin” (Gal. 3:22). The laws, of course, had a positive impact as well, keeping Israel in line until the coming of the promised offspring of Abraham, the Messiah (Gal. 3:24).

Once the Messiah came, he fulfilled the purpose of the laws on Israel’s behalf. Jesus was the faithful Israelite who truly loved God and neighbor. As the messianic King, he died to take the curse and consequence of Israel’s failure into himself in order to bring redemption. Now through Jesus, the offspring of Abraham, God’s blessing can finally come to all people regardless of their ethnicity, social status, or gender.

For Paul, requiring Torah observance from non-Jewish Christians just doesn’t make sense. It’s acting as if Jesus didn’t fulfill God’s promise or deal with our sins. It neglects the new freedom gained through Jesus’ resurrection and the gift of the Spirit, and it limits God’s promise and blessing to one ethnic family.

Galatians 5-6: Living by the Spirit and New Creation

Paul’s opponents might argue that the laws of the Torah are a proven guide to living according to God’s will. How will non-Jewish Christians learn without them? Paul responds in chapters 5-6 by describing how Jesus’ transforming presence through the Spirit is the key. Paul says that the laws of the Torah are good and wise. And they can be summarized, as Jesus did, in the command to love your neighbor as yourself (Lev. 19:18). However, the laws, as good as they are, didn’t give Israel the power to obey them. But the good news is that Jesus fulfilled the laws on our behalf. He now lives in us through the Spirit, making his people into new humans who fulfill the law by loving others.

Paul goes on to contrast the old and new humanity. The habits of the old humanity are obvious—behaviors that dehumanize people and destroy relationships and communities through selfishness, envy, divisiveness, sexual immorality, idolatry, and murder. While the laws of the Torah prohibited these behaviors, Jesus is the one who put them to death on the cross. When a person trusts in Jesus, living in dependence on the power of his Spirit, his life becomes theirs. This produces what Paul calls the fruit of the Spirit. It’s Jesus’ own way of life, which he wants to reproduce in his family so that they become people of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

The production of this fruit isn’t automatic, Paul says. It requires cultivation just like real fruit. In his words, “If we live by the Spirit, we have to keep in step with the Spirit” (Gal. 5:25). Doing so requires intentionality. We have to learn how to prune off our old habits and cultivate new ones. As we do so, we will be carried along by the Spirit as Jesus reshapes our minds and hearts, making us into people who love God and others. In this way, Jesus’ people fulfill what Paul calls the Torah of the Messiah (Gal. 6:2).

In the end, Paul concludes that the requirement of Christians to become Torah observant or be circumcised misses the point. What really matters is God’s new creation (Gal. 6:15), the new, multiethnic family of the Messiah. These are the people who are full of faith in Jesus, learning to love God and others through the power of the Spirit.