The Book of Job

About

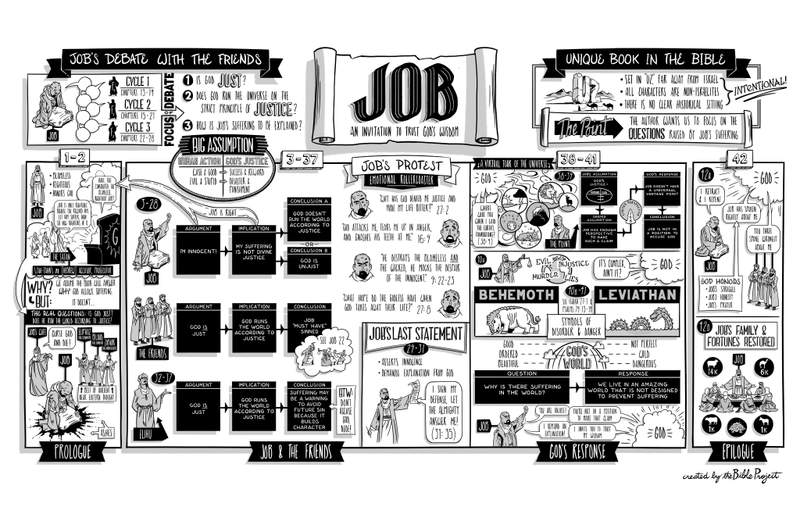

The book of Job opens with a curious courtroom scene where the satan, or the accuser, challenges God’s way of rewarding righteous people like Job. The satan says that Job is only acting righteous because of God’s generous provision. But if God were to let him truly suffer, then Job’s true character would emerge. God rejects that idea, saying Job will continue to live faithfully even in the face of intense suffering.

Using dense Hebrew poetry, the author lays out Job’s brutal experiences and his wife’s and friends’ speculations about why Job is suffering. Is he not a righteous man? Why would God allow this? Job accuses God of failing to operate the world with justice, and he asks God to explain himself. What unfolds after this exchange helps us see that God’s wisdom is more complex than we often imagine.

The Story of Job

The author introduces Job as an upstanding man from the land of Uz who honors God. We read about his large family and prosperous estate, and it becomes clear that Job is wealthy—a man with everything to lose.

The author then transports readers to a heavenly courtroom where God is meeting with spiritual beings. Among them is a figure called the satan, which in Hebrew means “the one opposed.” God presents Job as an admirable and righteous man. But the satan dismisses this, saying that Job only serves God because of his blessings and protection over Job. The opposer is sure that if God stopped treating Job so generously, Job would curse God. God knows that Job’s faithfulness is not based on circumstance, so he allows the satan to inflict suffering on Job’s life, affecting his family, riches, and health.

At this point, many of us are wondering why God would allow a good person to suffer this injustice. It’s an important question, and the prologue helps us get to the root: Does God’s justice mean he rewards and punishes people based on their behavior? And if good people suffer, does that mean God isn’t just? The book of Job explores this question and offers a surprising answer in the conclusion. But before we get to that, we’ll see how Job’s friends try to make sense of his suffering and God’s role in it.

Dialogue of Job and His Friends

Chapters 3-37 are full of dense Hebrew poetry that helps readers visualize a heated debate between Job and his friends, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar. The friends assume that God orders the world by a principle of retributive justice—if you’re wise and honor God, he will reward you with good outcomes, but if you are foolish and dishonor God, he will punish you with harsh circumstances. As the friends witness Job’s suffering, they conclude he must be guilty of wrongdoing. Job defends his integrity. While he agrees that bad deeds deserve punishment, he knows he’s innocent. So he speculates that God must be punishing him without cause. The friends passionately disagree, insisting that Job must have done something wrong.

Job and his friends argue back and forth in three cycles found in chapters 13-14, 15-21, and 22-28. Their debating continues until Job tires of responding to them and takes his complaints directly to God. His prayers show us the depth of his agony, confusion, and despair. He accuses God of being against him and guilty of coordinating all the injustices in the world. But then he realizes that can’t be right—God must be fair and all-powerful. But he still can’t reconcile why all these terrible things have happened to him, and he demands that God explain himself.

This section ends with the reply of a new friend, Elihu. He draws a more complex conclusion about why people might suffer. Elihu says that God may not be punishing them. Maybe God uses suffering for warning or building character. Unlike Job’s other friends, Elihu doesn’t claim to know why Job is suffering. But he is sure of one thing: Job is not qualified to judge God.

God’s Response to Job

In a surprising turn, God visits Job in a powerful storm and responds to his prayers. A whirlwind of rhetorical questions exposes Job’s lack of understanding. God asks whether or not Job helped him create the cosmos or set the constellations in place. Has he ever awakened the sun or managed the Earth’s weather? Would he like to oversee the world for a day, according to his narrow principle of justice? God’s questions dismantle many of Job’s assumptions about justice, proving that the world is far more complicated than he ever imagined.

God then goes on to describe two terrifying creatures, the Behemoth and Leviathan. These creatures symbolize the dangers that exist in God’s world, illustrating that while the world is good, it’s not always safe and does not operate as humans assume. God’s world is beautiful, but it is also wild and dangerous. Both are true, but God doesn’t explain why. By the end of God’s powerful speech, Job is convinced he would not even understand God’s answer. And this leads us to the final scene in the book.

Conclusion of the Story of Job

Job humbly admits his narrow thinking that led him to accuse God of injustice. Job does not have sufficient knowledge to comprehend or pass judgment on God’s reasoning. But even without full knowledge of how God orders the universe, he can still choose to trust God’s wisdom and good character.

The book concludes with a short epilogue, showing how God restores Job’s losses and defends his character to his friends. God says their explanations of justice were inaccurate and clarifies that Job spoke truthfully about him. While Job was wrong to accuse God of injustice, he was right to eventually turn away from his friends’ accusations and trust God. Admitting his struggle and continuing to bring his questions to God in prayer was a faithful act from Job, and God is pleased with Job’s humility, honesty, and commitment to receive answers from him.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some of the most common questions people ask online about this book.

Job is the central character in the book of Job in the Hebrew Bible. The book\'s anonymous author portrays Job as a morally good non-Israelite from the land of Uz who experiences tremendous suffering.

Learn more about Job’s story by watching these videos.

The author does not specify when the story takes place. However, historians and biblical scholars estimate that the author wrote it between the 7th and 4th centuries B.C.E.

The story takes place in the land of Uz, far from Israel. The author’s choice to spare many details about the setting (time and place) helps readers focus on the characters and plot development. However, the limited details reveal something meaningful. Dig into this deeper meaning by listening to the podcast episode below.

Many of us have experienced or witnessed misery and wondered how God can be just when there is so much pain in the world he created. How can God’s justice and human suffering coexist?

Job and his friends wrestle with this question too.

We see Job as a despairing man in agony, longing for answers. We also see Job’s friends struggling to help. At times, they are well-intentioned and seem to care for Job. But in other moments, they are angry, defensive, ignorant, and judgmental. Job’s friends assume that suffering is always the result of God’s judgment—that it is always a form of punishment. Since God is just and Job is suffering, Job’s friends argue, then Job must be guilty of some kind of evil. But Job knows he’s not to blame for anything that could warrant his intense suffering, so he concludes that God must be unjust.

Readers experience a cosmic, behind-the-scenes view of Job processing his circumstances—we get to listen in on God’s responses to Job and his friends. As the story unfolds, the author continues to dismantle the idea that suffering must be a form of divine punishment.

Learn more:

The book of Job points to a God who is always acting with goodness and justice, including the times when people are experiencing or causing pain. A person’s suffering does not automatically mean he or she is receiving divine punishment. Suffering in our world is more complex, and Job shows us what it looks like to trust God’s justice and wisdom in the face of harmful or misguided assumptions about pain and where it comes from.

Job realizes that he does not have sufficient knowledge to understand or pass judgment on God’s reasoning. Even without full knowledge of how God orders the universe, he chooses to trust God’s wisdom and good character. Job represents his grief by shaving his head and sitting in ashes, a common way of mourning in his world. In some ancient (and current) cultures, ashes symbolize death and mourning. Baldness symbolizes deprivation and a loss of strength.

Job loses everything—his property, his children, and his health—and he believes God is the one causing his suffering. Seeing nothing in his past that could justify such brutal treatment, Job questions God’s justice.

But through all of his questioning, Job still refuses to curse God. Instead, Job curses the day of his own birth. His blinding agony and confusion cause him to wish he had never been born.

The anonymous author does not overtly explain why Job praises God during his suffering, but a few details in the story offer clues.

When everything starts to fall apart, Job goes to his knees in worship and grief saying, “The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1:21). The word “Lord” in our English translations often stands in for the personal name of God, “Yahweh.” This shows us Job’s personal relationship with God, which is likely part of the reason he praises God.

When Job’s wife tells him to curse God, Job responds, “Shall we actually accept good from God but not accept adversity?” (Job 2:10). We also learn from Job’s prayer in Job 28 that, even though he cannot comprehend the complexities of divine wisdom, he still chooses to trust that God is truly good.

At the end of the book, God shows up in a whirlwind to respond to Job’s accusations. He guides Job on a virtual tour of the universe and asks him several rhetorical questions. Each question dismantles Job’s assumptions about justice, revealing that the world is more complex than Job had assumed.

Learn more: