The Book of Deuteronomy

About

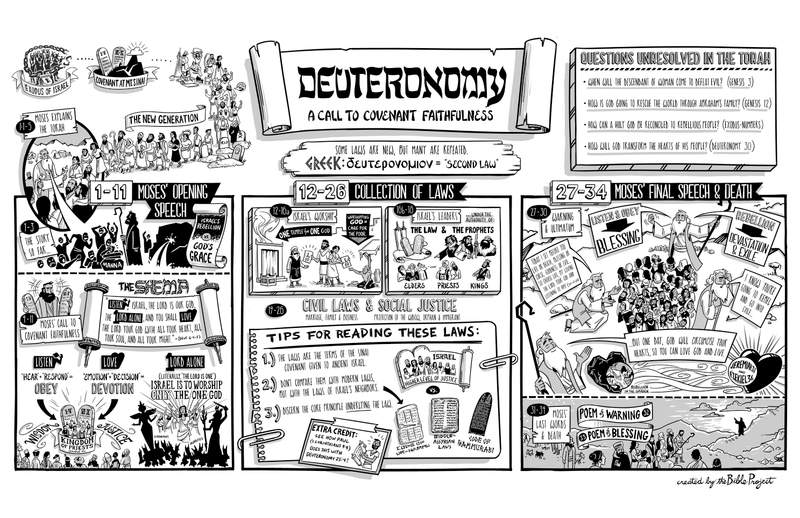

Deuteronomy is the fifth book of the Bible and the final book of the Torah. In the preceding books, Israel had left Egypt and stayed at Mount Sinai for a year, where they entered into a covenant with their God. Despite this amazing start, the Israelites struggled in their journey through the wilderness, and the entire Exodus generation was disqualified from entering into the promised land. Deuteronomy begins with Moses standing in front of the new generation, and his job is to explain the significance of the laws of the Torah (Deut. 1:1-5). This opening scene helps us understand the design and purpose of the book. It’s a series of speeches from Moses, who calls the next generation of Israel to be faithful to their covenant with God.

At the center of Deuteronomy is a collection of laws, which make up the terms of the covenant between God and Israel (Deut. 12-26). Some are new, but many are repeated from the laws given at Mount Sinai. This is actually where the book gets the name “Deuteronomy,” from the Greek word deuteronomion, which means “a second law.” Surrounding the laws in this book are two outer frames of Moses’ speeches (Deut. 1-11 and 27-34), each broken down into two parts (Deut. 1-3; Deut. 4-11 and Deut. 27-30; Deut. 31-34).

Deuteronomy 1-11: Moses Calls Israel to Faithfulness

Moses first summarizes the story so far, highlighting how rebellious the previous generation was in contrast with God’s constant provision and grace in the wilderness (Deut. 1-3). God brought his justice upon them, yes, but he did not abandon his covenant promises.

Next comes a series of passionate sermons in which Moses calls on the new generation to be faithful to the covenant (Deut. 4-11). He reminds them of the ten commandments and goes on into the centerpiece of this section, a famous line called the Shema.

“Listen Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD alone, and you shall love the LORD your god with all your heart, all your soul, and all your might.” -Deuteronomy 6:4-5

This became an important daily prayer in Judaism, and it brings all the themes of the book together. The word “listen” (shema in Hebrew) means more than simply “hear.” Its meaning includes responding to what you hear. In English we would say “obey.” Similarly, the word “love” in Hebrew also refers to more than simply an emotion or feeling. It’s about a wholehearted commitment and devotion to God that involves our wills and our emotions, our minds and our hearts.

Now, Israel’s obedience and devotion to the covenant serve a much larger purpose. Obedience to the laws will make Israel a unique people among the nations. Like God said at Mount Sinai, they will become “a kingdom of priests,” and Moses explains how. Israel has the chance to show the world the “wisdom and justice of God” (Deut. 4:5-8).

The other key idea of shema is that Israel was called to obey and to be devoted to “the Lord alone.” In Hebrew, it says literally that “the Lord is one.” In context, the point is that the Lord is the only God Israel is to worship and follow, and they are not to represent him with any physical image.

Israel is about to enter the land of Canaan, where people worship idol gods that represent various aspects of creation, such as the sun, weather, sex, and war. In Moses’ view, the worship of these gods degrades people and destroys communities, but obeying the God of Israel, the gracious creator God who redeemed them from slavery, will lead to life and blessing.

Deuteronomy 12-26: Laws on Worship, Leadership, and Civil Life

After Moses’ passionate sermons, we come next to the large collection of laws in the center of the book of Deuteronomy, which are roughly arranged by topic. The opening section is about Israel’s worship of their God (Deut. 12-16a). Israel was to have one central temple where the one true God is worshiped. God was also to be worshiped through Israel’s care of its poor. For example, all Israelites were to set aside one-tenth of their income to be given to the temple and another one-tenth, set aside every three years, to give to the poor. Many of these laws put Israel on the cutting edge of justice in comparison to their ancient neighbors, which was all part of their worship of God.

The following section outlines the character qualities of Israel’s leaders (Deut. 16b-18). Elders, priests, and kings were all placed under the authority of the covenant laws, which God would enforce by sending prophets to keep them accountable. In contrast to Israel’s neighbors, who thought of their kings as divine and a law unto themselves, Israel’s leaders were all subordinate to the law as well as the prophets.

Next, there are laws about Israel’s civil life (Deut. 19-26). They cover issues of marriage and family, business and the legal system, and community justice. Specifically, the difficult circumstances of widows, orphans, and immigrants are highlighted. Israel is to take extra care and make sure these people are supported in their towns. Finally, this section concludes with more laws about Israel’s worship.

Now, here are some tips for reading all these laws. Remember, these are the terms of the covenant between God and ancient Israel, which was a very different culture from our own. In other words, it’s not going to be helpful to compare them with modern laws from a different time and culture. These laws were given to set Israel apart from their neighbors. When you compare biblical laws with those of Israel’s neighbors in Babylon or Assyria, rules that at first seem bizarre or harsh become more clear. You can see God pushing Israel to a higher level of justice than was ever known before. Finally, try to discern what core principle of wisdom or justice underlies a particular law, and you’ll discover some really profound things. (Here’s some extra credit: Check out how Paul does this very thing in 1 Corinthians 9:9 when he quotes a law in Deuteronomy 25:4.)

Deuteronomy 27-34: Covenant Blessings and Curses

After going through the laws, Moses offers a final challenge to Israel that they should listen to and love their God (Deut. 27-30). He issues a warning and ultimatum. If Israel listens to and obeys their God, things will go well and divine blessing will abound. If they don’t listen and instead rebel, they will suffer from famine, plague, devastation, and ultimately exile from the land.

Moses then forces a decision: “Today I set before you life or death, blessing or curse, goodness or evil ... So choose life, by loving the Lord your God and listening to him” (Deut. 30:15-20).

Now, Moses hasn’t somehow forgotten the last forty years with these people. He’s not optimistic about Israel’s future, and so he continues with this: “I know that after I die, you’re going to rebel, turn away from God, and end up in exile.” It’s clear he doesn’t have high hopes, at least not for the people’s ability to obey.

However, all is not lost because Moses also says that when Israel finds themselves sitting in exile, at any point they can turn back to their God. And in response, God will, in Moses’ words, “circumcise your hearts, so that you may love him with your heart and soul and live” (Deut. 30:6). This vivid metaphor is saying that something is fundamentally wrong with Israel’s heart; it’s stubborn and hard—the same thing that’s wrong with all humanity. Going all the way back to humanity’s rebellion in the garden, Israel has also seized autonomy to define good and evil for themselves. Along with all humanity, they’ve ruined themselves and God’s good world, but that’s not the end of the story. Moses says that he knows that one day God is going to do something to transform the hearts of his people, so that they can actually listen to and love God from the heart and discover true life. This is the promise of the new heart, picked up by later biblical prophets (Jer. 31 and Ezek. 36).

Moses ends his speech with poems of warning (Deut. 32) and blessing (Deut. 33). And having made his point, Moses walks up onto a mountain and passes away.

Surprisingly, this is where the Torah draws to a close. Moses’ story has ended, but the biblical story is just starting. All the major plot tensions generated in the Torah are left totally unresolved.

- When is the descendant of the woman going to come and defeat evil (Gen. 3)?

- How is God going to rescue his world and restore blessing to all nations through Abraham’s family (Gen. 12)?

- How can God’s holiness be reconciled with continuously rebellious people (Exod.-Num.)?

- How will God transform the hearts of his people (Deut.)?

The Torah sets up all these problems, and to find their resolution, you have to keep reading.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some of the most common questions people ask online about this book.

“Deuteronomy” comes from the Greek deuteronomion, which means "second law.” This title is likely from the early Greek translation of Deuteronomy 17:18, which says that when Israel has a king, he should “write for himself this second law [deuteronomion] in a book.” The Hebrew text makes it clear that the verse is not talking about writing a different or new law, but making a copy of God’s law or “instruction” (Hebrew torah) so that the king can meditate on it and keep it (see Deut. 17:19-20).

The title Deuteronomy is appropriate to the whole book of Scripture because it focuses on Moses retelling Israel's story and restating many of the laws found in Exodus-Numbers. The book’s aim is to ensure that the second generation of Israelites, who weren’t at Mount Sinai when God originally gave the torah, understand the crucial importance of following God’s teaching in order to find life (Deut. 30:11-20).

Deuteronomy also recasts the torah to address the Israelites’ new situation of life in the promised land. For example, since the people will no longer travel together through the wilderness in a single camp set up around the tabernacle, the book talks about a central place in the land where the Israelites will go to worship God (Deut. 12), which is later identified with the temple in Jerusalem.

Deuteronomy provides Moses’ final sermons to the Israelites, which they receive before parting ways with Moses and entering the promised land under Joshua’s leadership. Most basically then, the book of Deuteronomy represents Moses’ final words to Israel before he dies.

But we can also understand the book of Deuteronomy as the representation of an ancient treaty, or covenant, between a “suzerain” (a great king) and a “vassal” (a lesser king or nation). Each part of an ancient suzerain-vassal treaty can be found in the book of Deuteronomy.

- An introduction identifies the parties to the treaty. In this case, Deuteronomy 1:1-5 explains that Moses is speaking the words of Yahweh to the Israelites.

- A historical prologue explains the history of the relationship between the suzerain and vassal. Here, Deuteronomy 1:6-4:49 recounts how God spoke to the Israelites at Mount Horeb (also called Sinai) and led them through the wilderness to the edge of the promised land, while also remembering how he brought them out of slavery in Egypt.

- The stipulations describe what the vassal needs to do in order to keep the treaty. So Deuteronomy 5-26 gives God’s instruction, or torah, that the Israelites need to follow to maintain their side of their covenant agreement with God.

- A document clause explains how the treaty documents will be stored—usually in the temples of both suzerain and vassal—and when they will be read. Deuteronomy 27:1-4 calls for writing the words of God’s torah on large stones, and Deut. 31:9-13 specifies that the torah should be read every seven years.

- Then the gods of the suzerain and vassal are called to act as witnesses to make sure the treaty is kept. But since Yahweh is the only true God, Deuteronomy calls Heaven and Earth (Deut. 30:19) and the Song of Moses (Deut. 31:19-22) as witnesses.

- Finally, a treaty lists blessings the vassal will receive if they keep the stipulations, and curses if they don't. So Deuteronomy 28 describes the blessings and curses the Israelites will experience, depending on whether they keep the terms of their covenant with God.

Deuteronomy uses a literary form that is familiar to the ancient Israelites, the suzerain-vassal treaty, to reaffirm the covenant relationship God made with the Israelites at Mount Sinai (Exod. 19-24).

In the book of Deuteronomy, Moses is the primary speaker, but he also quotes God's words directly. For example, in Deuteronomy 5:6-21, Moses recounts how God gave the Israelites the Ten Commandments, beginning with, “I am Yahweh your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” (Deut. 5:6, BP Translation). Moses speaks on God’s behalf because God chose him to be his mediator to the people.

At other times in the book of Deuteronomy, Moses recounts the words and complaints of the people, like when he reflects on their reluctance to enter the promised land (Deut. 1:27-28). By quoting these words from the prior generation, Moses encourages the current generation to respond differently than their parents, trusting God without fear.

At the end of the book, we hear God’s words to Moses, giving him final instructions about commissioning Joshua (Deut. 31:14). He also tells Moses to leave the Israelites with a song, usually called the Song of Moses (see Deut. 32), that will act as a witness to them when they stray and call them to turn back to God (Deut. 31:16-21).

In Deuteronomy, Moses addresses the second generation of Israelites after the exodus—that is, the children of those who were originally freed from slavery in Egypt. This new generation did not personally witness the plagues in Egypt or God parting the waters of the Red Sea (Exod. 7-15). And they were not at Mount Sinai when God appeared in fire and smoke, making a covenant with their parents (Exod. 19-24).

So even though they’ve seen God provide for them in the wilderness (Deut 8:3; see also Josh. 5:12) and protect them from attacking armies (Num. 21:21-35), they don’t have firsthand experience of the foundational events that formed them as God’s people. Instead, they’re relying on the testimonies and stories passed down to them from their parents.

Interestingly, Moses speaks to this second generation as if they stand in their parents’ sandals. He even says, hyperbolically, “Yahweh made this covenant not with our ancestors but with us, all of us who are here alive today” (Deut. 5:3, BP Translation). Moses emphasizes that God's covenant is not just a historical agreement with the past generation, but a living commitment with every generation of his people.

The laws in Deuteronomy do not directly apply to modern readers in the same way they did to ancient Israelites. But when understood in their historical context, they can teach us about God's wisdom and values.

For example, Deuteronomy 22:8 requires Israelites to build protective walls around the roofs of their houses to prevent people from injury by falling. While this law reveals God’s concern to protect human life, literally following it today would be odd (if even possible), because many homeowners have pitched roofs, and very few host large gatherings of people on their rooftops. That said, we can follow the goal of the law by acting in ways that protect human life and making sure our homes are safe spaces for welcoming others.

Some of the laws in Deuteronomy may seem strange or even harsh to modern ears. But when we compare them to ancient Near Eastern law and culture, we see how they’re designed to call the Israelites to higher standards of justice and compassion than their neighbors. These laws don’t represent God’s ultimate ideals for humanity (see Matt. 19:3-12 on Deut. 24:1-4). Instead, they invite people to move incrementally toward God’s ways of peace and love.

Also, a key concern in Deuteronomy is care for the vulnerable. Deuteronomy 10:18-19 calls the Israelites to love the foreigner, just as God does, remembering that they were once foreigners in Egypt. And Deuteronomy 24:19-22 instructs them to leave part of their harvest behind for foreigners, widows, and orphans. The New Testament picks up this concern by declaring that people express “pure worship” when they “care for orphans and widows in their distress” (Jas. 1:27, BP Translation). So Deuteronomy’s insights about God’s justice and compassion continue to guide followers of Jesus today.

As the Israelites prepare to enter the promised land, the key advice Moses offers them is to love Yahweh, their God, and walk in his ways (Deut. 6:4-9, Deut. 10:12-13, Deut. 11:1). He also warns them to not turn away from Yahweh or serve other gods, as this led to all sorts of problems in the previous generation (Deut. 4:15-24; see Exod. 17:1-7; Num 25:1-18).

God has called the Israelites to be holy—that is, set apart from surrounding nations. They are his “treasured possession” and will mediate his presence to the rest of the world as a “kingdom of priests” (Exod. 19:3-6; Deut. 7:6). He instructs them to reflect his justice by caring for the vulnerable among them—especially the foreigner, the orphan, and the widow (Deut. 24:17-21, Deut. 26:12-13). As they follow his teaching, they will embody his wisdom before the watching world and bring blessing to the nations (Deut. 4:5-8; see Gen. 12:3).

Near the end of Deuteronomy, Moses summarizes all his advice and warning by offering the Israelites a choice between life and death (Deut. 30:15-20), which mirrors Adam and Eve’s choice in the Garden of Eden (Gen. 2-3). Doing what’s right in their own eyes will lead to destruction, but following God’s wisdom will lead to life and blessing in the promised land.

In Deuteronomy 4:21-22, Moses explains that he will die outside the promised land because the people have provoked God’s anger against him. Numbers 20:2-13 records the fuller story.

Being without water in the wilderness, the Israelites grumble against Moses, questioning why they were brought out of Egypt to such a terrible place. So God tells Moses to speak to a rock, promising that water will come out. But instead, Moses strikes the rock with his staff—twice!—and boasts that he and Aaron will bring water out of the rock.

God explains that Moses and Aaron’s actions do not demonstrate reverence for him before the Israelites and, as a consequence, neither will enter the promised land. So in Deuteronomy 34, Moses ascends the top of Mount Nebo across the Jordan River from the promised land and dies atop the mountain.

God’s word brings life to humanity, and ignoring it leads to exile and death. Moses’ disobedience is part of a pattern that begins in the garden of Eden in Genesis 1-3. When Adam and Eve disobey God's command by eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and bad, they are exiled from the garden. Similarly, when Moses fails to follow God's instruction, he does not get to enter the promised land—Israel's new Eden.

In Deuteronomy, Moses retells earlier stories in a way that highlights how they are significant for the people of Israel now, particularly as they prepare to cross the Jordan River and enter into the promised land.

For example, Numbers 21:33-35 briefly recounts how Israel defeats Og, King of Bashan. But in Deuteronomy 3:1-11, we get an expanded account, including the detail that Og's bed is nine cubits (over 13 feet) long! Why does Deuteronomy add such detail in this updated version of the story?

In Numbers 13-14, the story tells us that Israel’s prior generation was afraid to enter the promised land because they’d seen and heard about its giant residents (see Num. 13:32-33). So Moses includes details about the battle of Og that the book of Numbers omitted, in order to remind the people they have already won a battle against a giant king. Just as God gave them victory over Og, God will also give them victory Moses retells the story to show that God will again give them victory over the strong enemies they’ll face when they cross into the land of Canaan.