The Book of 1 Peter

About

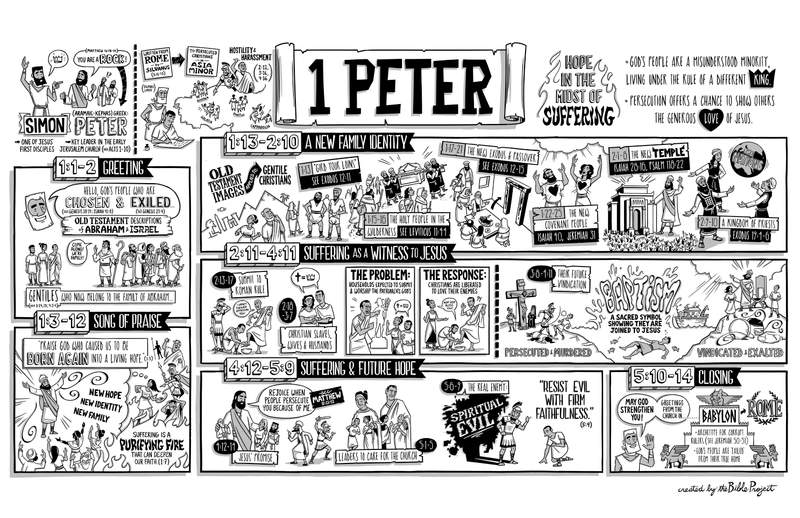

Peter’s name was Simon when he became one of Jesus’ first followers and part of the inner circle of the twelve disciples. When he made his confession that Jesus was the Messiah (Matt. 16:18-19), Jesus changed his name to Kephas—an Aramaic word meaning “rock,” which would later be translated into Greek as Petros, or Peter. Jesus promised that he would become a leader among the apostles to guide the messianic community in Jerusalem through its earliest years. If we look back at Acts 1-10, we can see how this promise proved to be true.

Eventually, Peter was called to carry the good news of Jesus beyond the borders of Israel, and decades into his work within the wider Roman world, he wrote this letter. We discover at the letter’s conclusion that Peter is in Rome (though he calls it Babylon), and we learn that, while Peter commissioned the letter, it was actually composed by his coworker Silvanus (1 Pet. 5:12-13).

This was a circular letter that was sent to multiple church communities in the Roman province of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). Peter learned that these mostly non-Jewish Christians were being persecuted and facing hostility and harassment from their Greek and Roman neighbors (1 Pet. 2:12; 3:16; 4:16). Peter wrote to encourage them in their suffering, and this context will help us understand the letter’s design and main themes.

The letter opens with a greeting in verses 1:1-2 and then moves into a poetic song of praise to God (1 Pet. 1:3-12). This poem introduces the key themes that are then explored in the next three movements, in which he affirms the new family identity of these Christians (1 Pet. 1:13-2:10), helps them to see their suffering as a way to bear witness to Jesus (1 Pet. 2:11-4:11), and encourages them to focus their future hope on the return of Jesus (1 Pet. 4:12-5:11).

1 Peter 1:1-12: Gentile Christians as Chosen Exiles

Peter opens by greeting these churches as the “chosen” people of God who are “exiled” around the world (1 Pet. 1:1). While he makes it clear that these Christians are Gentiles (1 Pet. 1:14; 1 Pet. 1:18; 4:3-4), Peter goes on to describe them with phrases from the Old Testament about God “choosing” Israel (Gen. 18:19; Isa. 41:8), the family stemming from Abraham who was himself an “exile and wanderer” (Gen. 23:4). This is a key strategy that Peter repeats throughout the entire letter. He wants these suffering Gentile Christians to see that, through Jesus, they now belong to the family of Abraham and are wandering exiles just as he was. Like their spiritual ancestors, they will likely be misunderstood and mistreated as they wait for their true home in the promised land.

This idea is found within the opening song (1 Pet. 1:3-12). He praises God for causing people to be “born again into a living hope” through Jesus’ resurrection and the power of the Spirit. God is inviting all people into a new family centered around Jesus, a family that has a new identity as God’s beloved children and a new hope of a world reborn by God’s love when Jesus returns as King. For people with this hope, suffering and persecution can be considered a strange gift. Suffering burns away false hopes and distractions like a purifying fire and reminds us of our true home. So, paradoxically, life’s hardships can actually deepen our faith and make it more genuine. From here, Peter moves into the body of the letter and explores these ideas in greater depth.

1 Peter 1:13-2:10: The New Family Identity of Jesus

Peter first develops the theme of their new family identity (1 Pet. 1:13-2:10) by taking memorable Old Testament images about the family of Israel and applying them to these Gentile Christians. Like the Israelites who left Egypt, they should “gird up their loins” (1 Pet. 1:13; Exod. 12:11) and leave their former life behind on the way to a new future. They are the “holy people” of God journeying through the wilderness (1 Pet. 1:15-16; Lev. 11:44) as well as the people of the new exodus, redeemed by the blood of Jesus, the ultimate Passover lamb (1 Pet. 1:17-21; Exod. 12-15). They are the people of the new covenant who have God’s word buried deep inside, restoring their hearts and minds (1 Pet. 1:22-25; Isa. 40:6-8; Jer. 31:31-34). Finally, they are the new temple built on the foundation of Jesus himself (1 Pet. 2:1-8; Isa. 28:16; Ps. 118:22), and they are the new kingdom of priests who serve God as his representatives to the nations (1 Pet. 2:9-10; Exod. 19:4-6; Isa. 43:21).

1 Peter 2:11-4:11: Suffering as a Way to Bear Witness to Jesus

By applying all these images to persecuted Gentile Christians, Peter places their suffering within the context of a new story. This leads into the next section (1 Pet. 2:11-4:11), where their persecution can actually help clarify their mission in the world. They are called to bear witness to God’s mercy among the nations. Peter first encourages them to submit to Roman rule, even if it’s oppressive (1 Pet. 2:13-17). While their persecution and suffering are indeed unjust, resisting with violence will solve nothing and betray the teachings of Jesus, who loved his enemies instead of killing them.

Peter then specifically highlights the difficult situation that enslaved Christians and wives faced when they lived in Roman patriarchal households that did not follow Jesus (1 Pet. 2:18; 3:7). Peter was well aware that giving allegiance to Jesus would generate suspicion because it was expected that everyone in the household would submit to and worship the patriarch’s gods. And while it is true that all Christians, including Roman wives and enslaved people, have been fully liberated by Jesus, they are not to demonstrate that freedom through rebellion. Rather, they are to resist evil in the same way Jesus did, by showing love and generosity to his enemies. And that’s what Peter calls these wives and enslaved people to do as well. But in homes where the husband is a Christian, it is a different story. These husbands were to treat their wives in a totally different way than their Roman neighbors by regarding them as equals before God who are worthy of honor and respect.

Peter is hopeful that this imitation of Jesus’ love and the upside-down Kingdom will give power to their words as they bear witness to God’s mercy and show people the beautiful truth about the way of Jesus. However, Peter is also a realist. He knows that these Christians will continue to be persecuted, so he reminds them of their future vindication (1 Pet. 3:8-4:11). He recalls how Jesus himself was unfairly persecuted and murdered by corrupt human powers. But, in reality, he was dying for the sins of his enemies and was vindicated and given resurrected life by the Spirit. That’s when he was exalted as King over all human and spiritual powers.

Peter goes on to show how baptism points to the same future vindication of Jesus’ persecuted followers. Like Noah, they’ve been saved through the waters not as a magic ritual but as a sacred symbol that shows their change of heart and desire to be joined to Jesus in his death and resurrection. So even if they are killed for following Jesus, their hope is in future vindication and exaltation alongside him.

1 Peter 4:12-5:14: Hope for Jesus’ Return

As we proceed into the final movement (1 Pet. 4:12-5:11), Peter recalls Jesus’ words that his disciples should consider it an honor and a joy to be persecuted like he was (1 Pet. 4:12-19; Matt. 5:11-12). Peter then calls on the church leaders to care for these suffering Christians (1 Pet. 5:1-5), showing the same kind of servant leadership that Jesus showed to his followers. Finally, Peter reminds these Christians of the real enemy they’re facing. This hostility isn’t just cultural or political; there are dark forces of spiritual evil at work inspiring hate and violence (1 Pet. 5:6-9). They are to resist this evil by staying faithful to Jesus and his teachings, anticipating his return and ultimate victory.

Peter concludes verses 5:10-14 with a prayer for divine strength and a greeting from the church in Rome, which he calls Babylon. Peter is adopting here the tradition of the Old Testament prophets, for whom the name “Babylon” became an archetype for any corrupt nation (Jer. 50-51). Rome has become the new Babylon and the empire where God’s people are exiled from their true home in the renewed creation.

Peter’s first letter is a powerful reminder of Christian hope in the midst of suffering. God’s people have been a misunderstood minority from the beginning. They should expect to face hostility because they live under the rule of a different king, Jesus. However, persecution can become a strange gift to followers of Jesus, offering a chance to show others the surprising generosity and love of Jesus, which is fueled by the hope of his return.