The Book of Nahum

About

One important aspect of the ancient TaNaK order of the Hebrew Bible is that the 12 prophetic works of Hosea through Malachi, sometimes referred to as the Minor Prophets, were designed as a single book called The Twelve. Nahum is the seventh book of The Twelve.

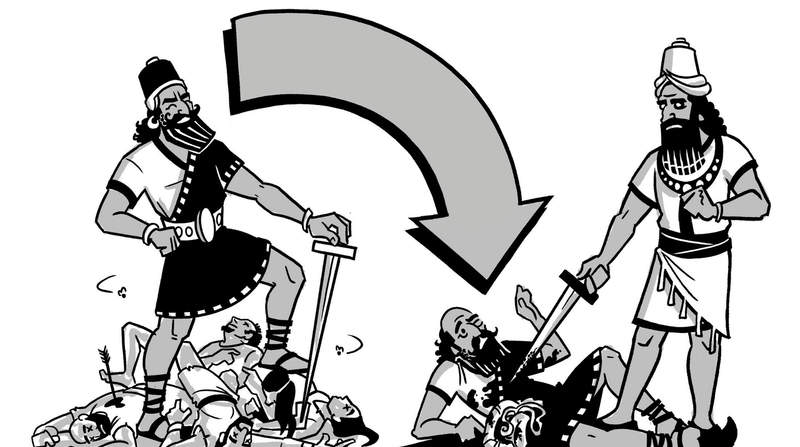

Nahum is a collection of poems announcing the downfall of one of Israel’s worst oppressors, the ancient empire of Assyria and its capital city, Nineveh. The Assyrians arose as one of the world’s first great empires, and their expansion into Israel resulted in the total destruction and exile of the northern kingdom and its tribes (2 Kgs. 17). Their armies were violent and destructive on a scale that the world had never seen before. Israel and its neighbors awaited the downfall of Assyria, which eventually came in the year 612 B.C.E. as the Babylonians rose up and began a rebellion that overtook Nineveh and brought down the Assyrian empire.

Chapter 2 depicts the fall of Nineveh in vivid poetry, while chapter 3 explores the downfall of Assyria as a whole. But this book isn’t just an angry tirade against Israel’s enemies. The introductory chapter shows that there’s way more going on in this short prophetic work.

Nahum 1: Nineveh as a Symbol for All Arrogant Empires

The book of Nahum opens with an incomplete alphabet poem that begins by describing a powerful appearance of God’s glory—similar to how the previous book, Micah, began and how the following book, Habakkuk, concludes. God, the all-powerful Creator, comes to confront the nations and bring his justice on their evil.

The poem opens by quoting the famous line from God’s self description after the golden calf incident in Exodus 34:6-7. “The Lord is slow to anger and great in power, and he won’t leave evil unpunished.” The rest of the poem goes back and forth, contrasting the fate of the arrogant, violent nations with the fate of God’s faithful remnant. While God brings down all the arrogant empires, he will also provide refuge for those who humble themselves before him.

Now, this is interesting because it seemed like this book was only going to be about Assyria. If we look closer, we find that in the Hebrew text of Nahum, Nineveh is never actually mentioned by name in chapter 1. Also, as Nahum describes the downfall of Assyria, he does so with the same language Isaiah used to describe the fall of Babylon that happened much later (Nah. 1:8-9; Nah. 1:14; Isa. 10; Isa. 14). Not only that but Nahum also describes the downfall of the bad guys as “good news for the remnant” of God’s people—a direct allusion to Isaiah’s good news about the downfall of Babylon (Nah. 1:15; Isa. 52:7).

All of these little details from chapter 1 come together and make a key point: For Nahum, the fall of Nineveh is an example of how God is at work in history. He won’t allow arrogant or violent empires to endure forever. This is very similar to the message of the book of Daniel. Assyria stands in a long line of violent empires throughout history, and Nineveh’s fate is a memorial to God’s commitment to bring down the arrogant in every age.

Nahum 2-3: The Downfall of Assyria

With this perspective in mind, the book continues by putting its focus back on Assyria. Chapter 2 describes the battle at Nineveh and the overthrow of the city in progressive stages. We see the front line of Babylonian soldiers, the charge of the chariots, the chaos on the city walls as the city is breached, the slaughter of Nineveh’s people, and finally, the plundering of the city. Chapter 3 describes the results of the city’s downfall for the empire as a whole. Nahum announces a woe upon the city, whose kings built it with the blood of the innocent—an image of how injustice was built into the very system that made the nation successful. Their violence has sown the seeds of their own destruction, and so Assyria will fall before Babylon.

The book concludes with a taunt against the fallen king of Assyria, who’s stricken with a fatal wound. No one from any of the nations he has oppressed offers help. Instead, they celebrate his demise, and that’s where the book ends, describing this grim party.

Nahum is a gloomy book, but it’s important to see how Nahum’s message addresses the tragic and perpetual cycles of human violence, oppression, and suffering. Human history is filled with tribes and nations elevating themselves and using violence to take what they want, always resulting in massive loss of innocent lives. The book of Nahum, using Assyria and Babylon as examples, says that God is grieved and cares about the death of the innocent and that his goodness and justice compels him to orchestrate the downfall of oppressive nations. God’s judgment of evil is good news, unless, of course, you happen to be Assyria.

This brings us all the way back to the conclusion of that first poem: “The Lord is good, a refuge in the day of distress. He cares for those who take refuge in him” (Nah. 1:7). The book invites every reader to humble themselves before God’s justice and trust that, in his time, he will confront the oppressors of every time and place.