The Book of Song of Songs

About

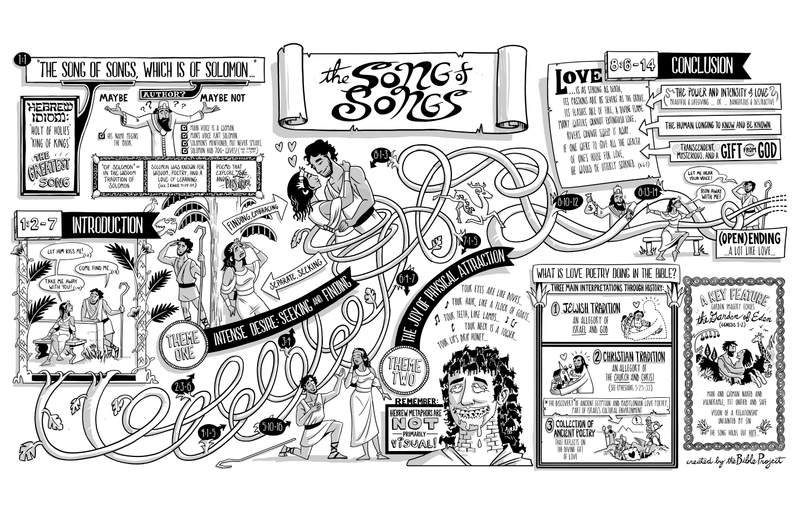

Song of Songs is a well-known but little-understood book of the Bible made up of eight chapters of ancient Israelite love poetry. While there is an introduction and a conclusion, the book doesn’t have a rigid literary design. It’s a collection of poems that are not meant to be dissected but rather read and enjoyed as a flowing whole.

The first line of the book declares that it’s “the Song of Songs,” a Hebrew idiom similar to “holy of holies” or “king of kings.” It’s a Hebrew way of saying that something is the greatest. This song is the greatest song of all.

We’re also told that this song is “of Solomon,” which could be taken to mean that he’s the author. However, as we read the poems, we find that the main voice belongs to a woman called “the beloved.” And while there is a male voice in the poems, it is not Solomon’s. He is mentioned in the poems, but never as a speaker (Song 3:7-11; Song of Songs 8:11-12). Besides, you have to admit that Solomon is an odd candidate for the author, given the fact he had some 700 wives (1 Kgs. 11:1-3)! This contrasts the two lovers in the Song of Songs. They are the only ones for each other.

The “of Solomon” more likely means “in the wisdom tradition of Solomon.” Solomon was known for his wisdom and poetry as well as his love of learning about every part of life (1 Kgs. 4:29-34). He became known as the father of wisdom literature in Israel, and here his legacy is carried on through a collection of poems that explore the human experience of love and sexual desire.

Song of Songs 1-8: The Longing, Seeking, Passion, and Power of Love

The opening poem (Song 1:2-7) introduces the basic theme of the book. We hear the voice of a young woman who delights in her man, who is a shepherd. She’s not yet married to him, but it becomes clear that they’re engaged and can’t wait to be together. From there, the poems flow back and forth between the woman’s voice and the man’s, shifting from scene to scene without any linear sequence or clear storyline. The poems instead move in symphonic cycles, where key images and themes get repeated and developed.

One of the basic themes uniting the poems is the intense desire the couple has for each other, expressed through their constant “seeking” and “finding.” After the opening poem, they’re separated but on the hunt for each other. The woman calls out, waking from a dream, and goes looking for her lover more than once (Song 2:3-6; Song of Songs 3:4; Song of Songs 8:1-3). When they end up finding each other, they embrace, and right when things get a bit racy, the scene suddenly ends and a new one begins with them separated once again.

Another repeated theme is the joy of their physical attraction to each other. At multiple points they pause to describe each other with elaborate metaphors (Song 4:1-5; Song of Songs 5:10-16; Song of Songs 6:4-7; Song of Songs 7:1-5). Here, it’s helpful to know that images and metaphors in Hebrew poetry are not primarily visual. If you try to paint a picture based on the metaphors, you’d end up with something that looks pretty wild! What you’re supposed to do instead is reflect on the meaning of the images as they relate to the man and woman.

As you read through these poetic cycles, the tension builds on their desire, joy, and attraction for each other. The spiraling repetition becomes a poetic way of heightening and focusing on the mystery and power of sexual love. It all comes together in the conclusion, which pauses to summarize what these poems are all about.

“Love is as strong as death, its passions are as severe as the grave. Its flashes are of fire, a divine flame. Many waters cannot extinguish love, rivers cannot sweep it away. If one were to give all the wealth of one’s house for love, he would be utterly scorned.”

The poem highlights the power and intensity of love. It’s beautiful, consuming, and dangerous. Like fire, it can destroy people if abused, but it can be life-giving if protected and nurtured. Ultimately, love expresses the insatiable human longing to know and be fully known and desired by another. Love is one of the most transcendent and mysterious experiences in human life, and, as part of the Bible’s wisdom tradition, this book says that it’s a gift of God.

After this, we suddenly find an odd poem (Song 8:10-12) about Solomon trying to do what the previous poem said was impossible, to buy love. The woman roundly rejects Solomon’s offer, and the book concludes with the characters of the man and woman separated once more and back on the hunt for each other. He calls to hear her voice (Song 8:13), and she begs him to run away with her (Song 8:14). And that’s how the book finishes—open-ended. It’s a lot like true love, which never really concludes because there’s always more to discover and pursue in your beloved. Just as true love has no end, neither does this book.

Interpretations of the Song of Songs

Now, throughout history, the big question raised by the book of Song of Songs is: What on earth is love poetry doing in the Bible? There have been three main interpretations of the book through history. In Jewish tradition, it was read as an allegory, with each character acting as a symbol. The woman is Israel, the man is God, and their love is a symbol of the covenant between them and the giving of the Torah. This view flowed into Christian tradition, but the characters were swapped. It’s about Christ’s love for his people and the Church.

This interpretation was inspired by Paul’s words in Ephesians 5:25-33, that a Christian husband’s love for his wife is a symbol of Christ’s love for the Church. However, in the last century, archaeological discoveries among Israel’s ancient neighbors in Egypt and Babylon have turned up all kinds of ancient love poetry, and it’s full of imagery and language very similar to the Song of Songs. In other words, love poetry was a meaningful part of Israel’s cultural environment. It should not surprise us to find it in the wisdom literature of the Bible. This has led most scholars today to view the Song as what it presents itself to be, a collection of Israelite love poetry reflecting on the divine gift of love.

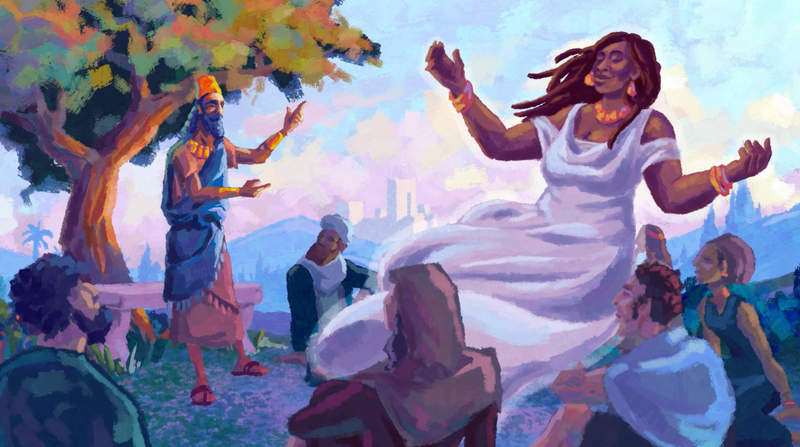

However, that doesn’t mean it’s only ancient love poetry. There’s a key feature to these poems that sticks out when they’re read as part of the Hebrew Bible, and that’s the overwhelming use of garden imagery. There are powerful echoes of the garden of Eden and the idyllic scene of the first married couple in Genesis 1-2. The images of the man and woman naked and vulnerable yet unified and completely safe with each other (Gen. 2:23-25) resonate in the background of the Song. It’s as if, through these poems, we’re witnessing the love of a couple whose relationship is untainted by selfishness and sin.

So the Song of Songs holds out hope. Even though our relationships are often distorted by selfishness, love is a transcendent gift that’s meant to point us to something greater, the gift of God’s love that will one day permeate and transform his beloved world.

This beautiful hope is what the “Greatest of All Songs” is about.