The Book of Lamentations

About

Lamentations is a unique book in the Old Testament. It contains five poems from an anonymous author, who survived and is reflecting back on Babylon’s siege of Jerusalem and the destruction and exile that followed (2 Kgs. 24-25).

The fall of Jerusalem and the exile was the most horrendous catastrophe in Israel’s history up to this point. God had promised Abraham the land of Canaan and had given David victory to make Jerusalem Israel’s capital. This city is where the kings from the line of David lived, where Solomon built the temple for Israel’s God, and where the priests maintained the rituals of Israel’s worship. After 500 years of all this history, in the summer of 587 B.C.E., the city fell to Babylon and everything was lost. The book of Lamentations is a memorial to the pain and confusion of the Israelites that followed the destruction.

Lament in the Larger Story of the Bible

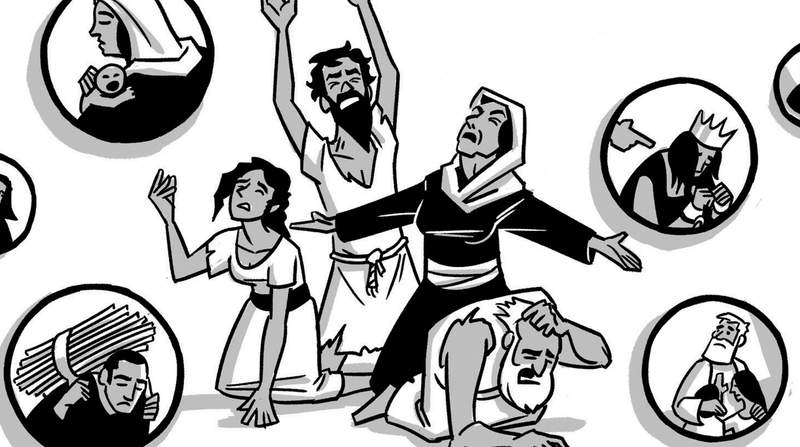

Now, the lament poems found here are not unique in the Bible, as there are many of them found in the book of Psalms (Ps. 10; Ps. 63; Ps. 69; Ps. 74; Ps. 79). These biblical poems of lament are a form of protest. They draw everyone’s attention, including God’s, to the horrible things that happen in his world that should not be tolerated. They are also a way of processing emotion. In these poems, God’s people vent their anger and dismay at the ruin caused by sin and violence. Finally, they give a voice to our confusion. How does our suffering relate to God’s character and his promises? Lament poems are a full-blown emotional explosion, and none of this is looked down upon in the Bible. Just the opposite, these poems give a sacred dignity to human suffering, as these human words of grief addressed to God have become part of God’s word to his people.

The design of the five poems in the book of Lamentations is very intentional and part of the book’s message. Chapters 1-4 are made up of acrostics, or alphabet poems, in which each poetic verse begins with a new letter of the Hebrew alphabet, consisting of 22 letters. This very ordered and linear structure is a stark contrast to the disordered pain and confused grief explored in the poems. It’s like Israel’s suffering is explored A to Z, trying to express that which is inexpressible.

Lamentations 1: Grief, Shame, and Trauma Personified in Lady Zion

Chapters 1 and 2 each have one verse per letter, giving them a similar design, but they differ greatly in their themes. Chapter 1 focuses on the grief and shame of a figure called Lady Zion as the poet personifies the city of Jerusalem as a widow, also referred to as the daughter of Zion. She sits alone, bereaved of her loved ones, devastated, and with no one to comfort her. When Lady Zion speaks, she calls on the Lord to notice her fate. It’s a powerful metaphor. Through this imagery, the poet shows that the city’s destruction brought a new level of psychological trauma on the Israelites that can only be expressed as a funeral, as they mourn the death of a loved one.

Lamentations 2: The Fall of Jerusalem and God’s Wrath

Chapter 2 focuses on the fall of Jerusalem and how it was a consequence of Israel’s sin brought about by God’s wrath, a key word in this poem. Now, it’s important to remember that in the Bible, God’s wrath is not spontaneous, volatile anger. The biblical poets and prophets use this word to talk about God’s justice. Israel entered a covenant agreement that they have been violating for centuries through their worship of other gods and allowing injustice towards the poor. While God is slow to anger, he does still get angry at human evil and will eventually bring his justice in the form of punishment. In the case of Jerusalem, that meant allowing Babylon to conquer the city. Chapter 2 acknowledges that God’s wrath was justified, but this doesn't keep the poet from lamenting and asking God to once again show compassion.

Lamentations 3: Hope for Justice in the Midst of Grief

Chapter 3 breaks the design pattern by having three verses per letter, making it the longest poem in the book. The voice is that of a lonely, suffering man who speaks as a representative of the entire people of Israel. What’s interesting is that this chapter is full of language drawn from other parts of the Old Testament, including the laments of Job (Job 3), important lament psalms (Ps. 22; Ps. 69), and even the suffering servant poems in Isaiah (Isa. 53). The poet sees his hardship as a form of God’s justice, just as chapter 2 asserted. But, paradoxically, this gives the poet hope and leads him to offer the only optimistic words in the book.

“Because of the Lord’s covenant faithfulness, we do not perish. His mercies never fail. They are new every morning. How great is your faithfulness, O God. So I say to myself, ‘The Lord is my inheritance, Therefore I will put my hope in him.’” (Lam. 3:22-24)

If God is consistent enough to bring his justice on Israel’s evil, then he will also be consistent with his covenant promises and not allow evil and sin to get the last word. For this poet, God’s judgment becomes the seedbed of hope.

Lamentations 4: Contrasting Life Before and During the Babylonian Siege

Chapter 4 goes back to the same acrostic structure as chapters 1 and 2. It’s a vivid and disturbing depiction of the two-year siege. The poem contrasts how great things were in the Jerusalem of the past with how terrible it was during the siege. Children once laughed in the streets; now they beg for food. The wealthy once ate lavish meals; now they look for whatever they can find in the dirt. The royal leaders were once full of splendor; now they are famished, dirty, and unrecognizable. Their anointed king from the line of David has now been captured and dragged away. The poem’s power comes from the shock of these contrasts, exploring the depth of the suffering Israel has brought on itself.

Lamentations 5: A Communal Prayer for God’s Mercy

The final poem is unique and completely breaks the design pattern. It’s the same length as the previous acrostic poems in that there are 22 lines, but the alphabetical order is gone. It’s as if the poet can’t hold it together anymore and his grief has exploded back into chaos. The poem is a long communal prayer for God’s mercy. Israel begs God not to ignore their pain or abandon them. The poem also offers a long list of all the different kinds of people who were devastated by Jerusalem’s fall and asks God not to forget them. Here, we see how lament poems can be written on behalf of others to give expression to their pain. Suffering in silence is not a virtue in this book. God’s people are not asked to deny their emotions. Rather, they are to voice their protest, to vent, and to pour it all out before God.

The book ends with something of a paradox. The poet acknowledges that God is the eternal King: “You, Lord, reign as king forever!” (Lam. 5:19) But Israel’s circumstances make it feel like God is nowhere to be found: “Why do you forget and forsake us?” (Lam. 5:20) The final words leave the tension unresolved: “Unless you’ve totally rejected us …” (Lam. 5:22). The poet doesn’t offer a nice, neat conclusion, just as we don’t experience simple conclusions to our pain.

The story of the Bible doesn’t end here, but this important book shows how lament and prayer are a crucial part of the journey of faith in a broken world.